The Red River Valley tornado outbreak of April 10, 1979 is one of the most significant tornado outbreaks that ever occurred in western north Texas and southern Oklahoma. To commemorate this event, the National Weather Service in Norman, Oklahoma has compiled a large amount of information including: tornado photos of the Wichita Falls, Vernon, Seymour, and Harrold, TX tornadoes; damage photos; images of radar and satellite data; other maps and diagrams of the event; and storm data for Oklahoma and western north Texas. We would like to give special recognition to Don Burgess of the Cooperative Institute for Mesoscale Meteorological Studies (CIMMS) in Norman for compiling and archiving most of the information contained within these web pages.

Two reports can be found on this web site. The NOAA Natural Disaster Report 80-1, "The Red River Valley Tornadoes of April 10, 1979" is available, and a synopsis and discussion of the event by Don Burgess can also be perused from this site. Excerpts from the Texas Department of Water Resources publication, "A Review of Texas' Weather in 1979: The Year of Devastating Tornadoes and Flash Floods," is also available.

Ingredients for a devastating severe weather event were beginning to come together on the morning of April 10. At the surface, an already strong low pressure area in southeast Colorado was beginning to deepen further, and a warm front was starting to lift northward from central Texas. To the south of the warm front, moist, unstable air was streaming northward. In the upper atmosphere, the nose of an extremely strong jet stream wind maximum was moving eastward through northern Mexico, preparing to turn northeastward and take aim on Texas and Oklahoma.

By afternoon, the warm front had lifted to the vicinity of the Red River, and a new low pressure area had formed near Childress. A dry line had formed from the Childress low southward, and temperatures had become very warm in west Texas. Aloft, the strong wind maximum was over the Red River area, producing significant vertical wind shear. Severe, tornado-producing, thunderstorms erupted along the dry line and moved eastward along and north of the warm front, continuing into the night in central and northeast Oklahoma.

After dark, another jet stream wind maximum moved northeastward into west central and northern Texas, sparking a second round of severe thunderstorms and tornadoes. The night time tornadoes, although strong, were not as devastating as the ones that occurred in the Red River Valley during the afternoon. Overall, the outbreak produced nearly 30 tornadoes and a large number of damaging wind and severe hail reports.

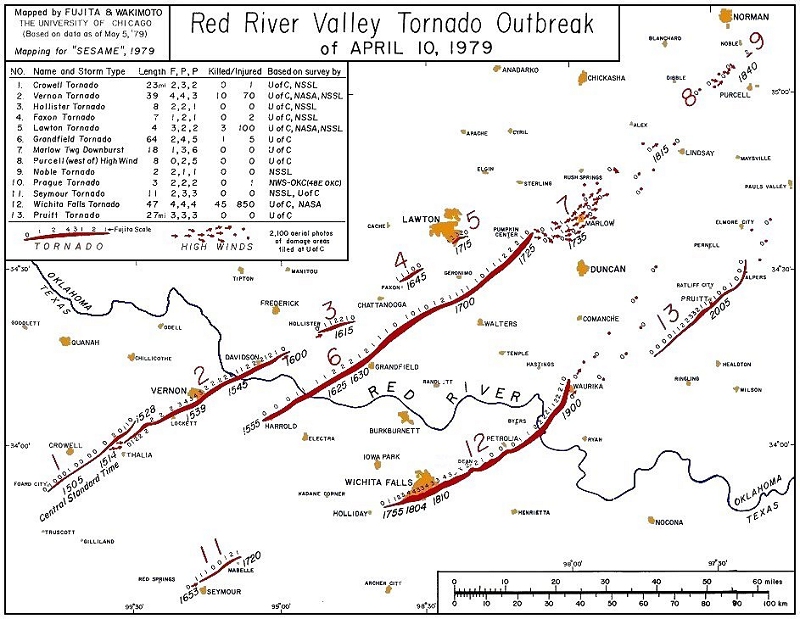

Three isolated supercells, forming in mid afternoon, moved northeastward as a trio and were responsible for the worst part of the outbreak. The northern supercell, the Vernon-Lawton storm, produced its first tornado at 1505 CST (3:05 PM) south of Crowell, TX. About 1540 CST (3:40 PM), a tornado devastated the southeastern portion of Vernon, TX (11 fatalities). Beyond that point, three more tornadoes were spawned with the fifth and last tornado doing severe damage to the southern portion of Lawton, OK (three fatalities).

The middle supercell, the Harrold-Grandfield storm, produced the longest-track tornado of the outbreak (64 mile path length) at 1555 CST (3:55 PM). A Doppler radar view of the three supercells is available. Fortunately, the strong and wide Harrold-Grandfield tornado spent its entire life in rural areas not striking any towns, but coming close to Harrold, TX (one fatality) and Grandfield, OK.

The southern supercell, the Wichita Falls storm, produced its first tornado at 1653 CST (4:53 PM) near Seymour, TX. The storm's second tornado, the terrible Wichita Falls tornado, formed at 1755 CST (5:55 PM) to the southwest of the city and moved through the southern and eastern sides of Wichita Falls shortly after 1800 CST (6:00 PM). The tornado finally ended near Waurika, OK after traveling 47 miles. The Wichita Falls storm produced a third and final tornado about 2000 CST (8:00 PM) near Pruitt, OK.

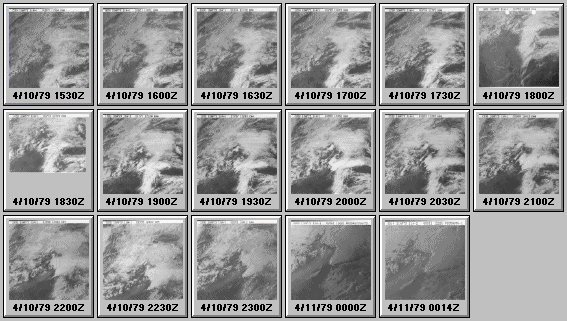

The Wichita Falls storm formed north of Abilene, TX. It generally moved to the northeast, but turned to the right along the middle of its path, the period during which it produced its violent tornado. During its life, radar-derived storm tops exceeded 50,000 feet and reflectivities were higher than 50 dBZ. It is interesting to note that the Seymour and Wichita Falls tornadoes both formed during periods of relative decline in storm-top height and reflectivity values, a characteristic that has been noted for a number of supercell storms that have produced several cycles of tornadoes. In particular, note the sharp decline in reflectivity near the genesis time and during the life of the Wichita Falls tornado with maximum values less than 45 dBZ for a brief period. During this period, large hail was occurring in the central and northern portions of Wichita Falls as the tornado devastated the southern portion of the city. No explanation for the unusually low reflectivity values with that phase of the storm (sensed by several radars) has been developed.

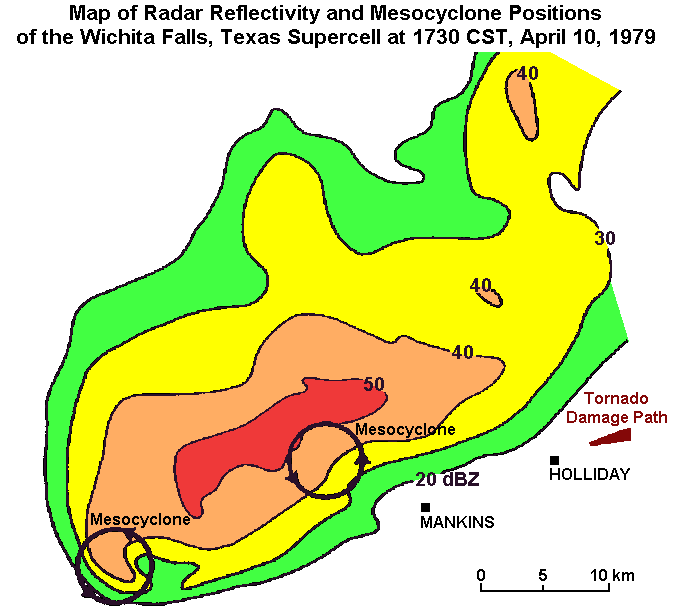

The Norman Doppler radar was used to collect dense data (0.5o azimuth spacing and 150 meter gate spacing) on the Wichita Falls storm during the interval leading to the formation of the violent tornado. At 1730 CST (5:30 PM), a core of greater than 50 dBZ and two mesocyclones were seen with the storm. The northeastern mesocyclone in the mesocyclone pair was the occluding parent circulation of the Seymour tornado while the southwestern mesocyclone in the pair was the developing parent circulation of the Wichita Falls tornado. By 1800 CST (6:00 PM), the storm had taken on a very classic supercell look with the tornado-associated mesocyclone and hook echo in the right rear portion of the echo. Note that the 50 dBZ core was no longer evident.

The Wichita Falls tornado formed several miles southwest of the city in Archer County, and traveled over mostly open terrain. With an east-northeast movement, it entered Wichita County and damaged a few rural homes and a string of metal high-voltage towers. Moving into the city, the tornado first struck Memorial Stadium and McNiel Junior High School (location #1 on the damage path diagram), severely damaging both structures.

The formation of the tornado and its movement toward the stadium and junior high were captured by Wolfgang Lange from the front of his apartment complex which was located across the street from the junior high (location #2). After taking his last picture of the approaching tornado, Mr. Lange retreated to the apartment complex laundry room and hid between heavy commercial washers and dryers, escaping with only minor injuries. On the first street of houses to the northeast of Lange's apartment complex, Robert Molet also photographed the approaching tornado (location #3).

Unlike Mr. Lange, Mr. Molet did not have an unobstructed view of the western horizon and did not immediately recognize that the threatening cloud was a tornado. Thus, he stood in his backyard driveway and photographed the destruction of the apartment complex and the beginning of destruction in his neighborhood. Mr. Molet continued to take photographs until the wind blew him into his garage. Although his house was completely destroyed, Mr. Molet escaped with only minor injuries as his pickup truck was blown over him, protecting him from the worst winds and debris.

The tornado's first fatalities were recorded in the apartment complex and adjoining housing area. Continuing east-northeast, the tornado severely damaged commercial building along Southwest Parkway, including total destruction of the Southwest National Bank Building except for its vault (location #4). To the north of Southwest Parkway, the tornado destroyed many houses in the Western Hills Addition. Further eastward, most houses in the Faith Village Addition were destroyed, and Ben Milam Elementary School was severely damaged (location #6). The tornado was photographed from the south during this period by Pat Blacklock location #5). In the latter Blacklock photographs, the gust front and associated strong west winds to the south of the tornado can be seen producing waves on Lake Wichita and kicking up spray from the lake.

As the tornado crossed Kemp Boulevard., several commercial businesses, including a restaurant, were destroyed with several additional fatalities. The tornado's worst winds generally missed the Sikes Senter Shopping Mall to the South, but a few of the stores were heavily damaged and many cars in the mall parking lot were blown some distance and stacked on top of each other. Beyond the shopping mall, the tornado crossed a greenbelt area, skirted Midwestern State University on its south side, and severely damaged several more housing additions (Colonial Park, Hursh, Southmoor, Southwinds, and Southern Hills). During this interval, the tornado was photographed by Professor Joe Henderson of Midwestern State University from the Ligon Coliseum (location #7). The tornado was also captured on film by Troy Glover from the roof of the Bethania hospital (location #8).

A number of people tried the flee from the tornado as it crossed the south side of the city by getting in cars and driving east on Southwest Parkway, north on US Highway 281 and east again on US Highway 287. The tornado blew many of those vehicles off those roadways, inflicting numerous fatalities. There were a total 42 tornado fatalities in Wichita Falls, of which 25 were vehicle related. Sixteen of the 25 got in vehicles to evade the tornado, and 11 of the 16 homes which were left did not incur damage by the tornado. Before leaving the east side of the city, the tornado destroyed the Sun Valley housing area, the Sunnyside Heights Mobile Home Park, and several large commercial businesses, including the Levi Strauss Plant.

Northeast of Wichita Falls, the tornado entered Clay County and changed its appearance. As seen in the photographs by Winston Wells (location #10), the tornado became multi-vortex, displaying as many as five satellite vortices rotating around the center of circulation. In this stage, the tornado did extensive damage just south of Dean and near Byars, destroying a large number of rural homes, but causing no more fatalities

The suffering and destruction caused by the Wichita Falls tornado is nearly inconceivable. The passage of a violent tornado through an 8-mile section of a city is an almost unheard-of natural disaster. In addition to the 42 fatalities directly caused by the tornado, three more people died of heart attacks and other illnesses during the stress of the tornado's passage. The number of reported injuries approached 1,800 although hundreds of additional minor injuries were never recorded

Total property damage in Wichita Falls was estimated at $400,000,000 (in 1979 dollars). Over 3,000 homes were destroyed and another 1,000 were damaged, and over 1,000 apartment units/ condominiums were destroyed and another 130 damaged. In addition, approximately 140 mobile homes were destroyed, two schools were demolished and 11 others sustained serious damage. Over 100 commercial businesses, some of them large manufacturing concerns, were destroyed. It is estimated that 5,000 families, containing 20,000 residents, were left homeless in Wichita Falls. Such a total would mean that between 10% and 20% of the population of the city was displaced by the tornado. To put the deaths and property damage in perspective, it should be noted that as many as 42 people have not been killed in the United States by a single tornado in the 20 years since the event, and the total property damage of $400,000,000 still stands as the most costly tornado in American history.

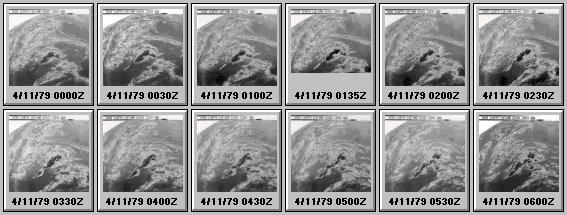

After the tornado, a thorough investigation of the damage was performed by Texas Tech University, Institute for Disaster Research, and the University of Chicago. Dr. Ted Fujita of the University of Chicago used these surveys to estimate the F-scale and probable wind speeds associated with the tornado. A detailed mapping of each house and public/commercial building in the city led to the construction of an F-scale map. Damage as severe as F4 was found along most of the track across the city. One somewhat unique characteristic of the damage was the wide swath F4 damage; many violent tornadoes produce only a narrow swath of their most intense damage. The width of the F4 damage in the Wichita Falls tornado approached 0.5 miles in the area of Faith Village and Ben Milam Elementary School (location #6).

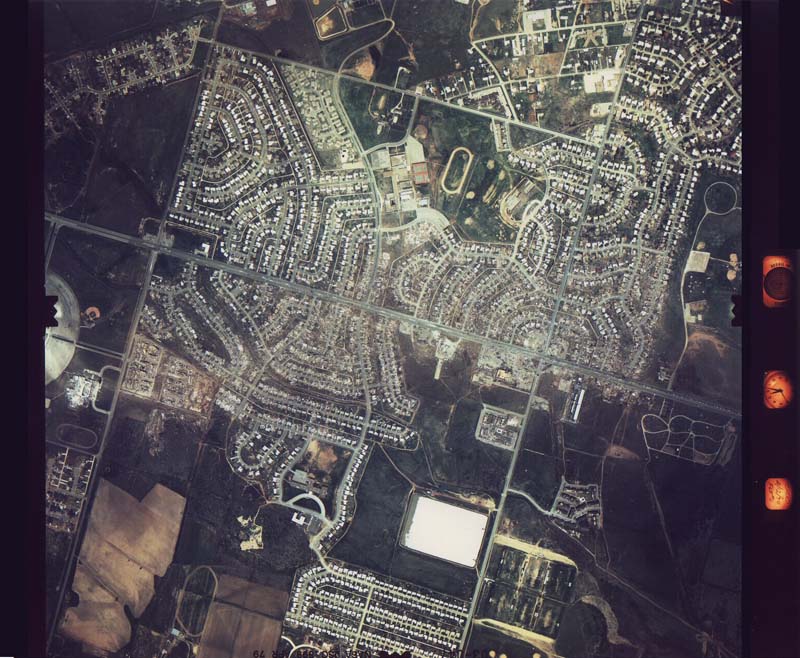

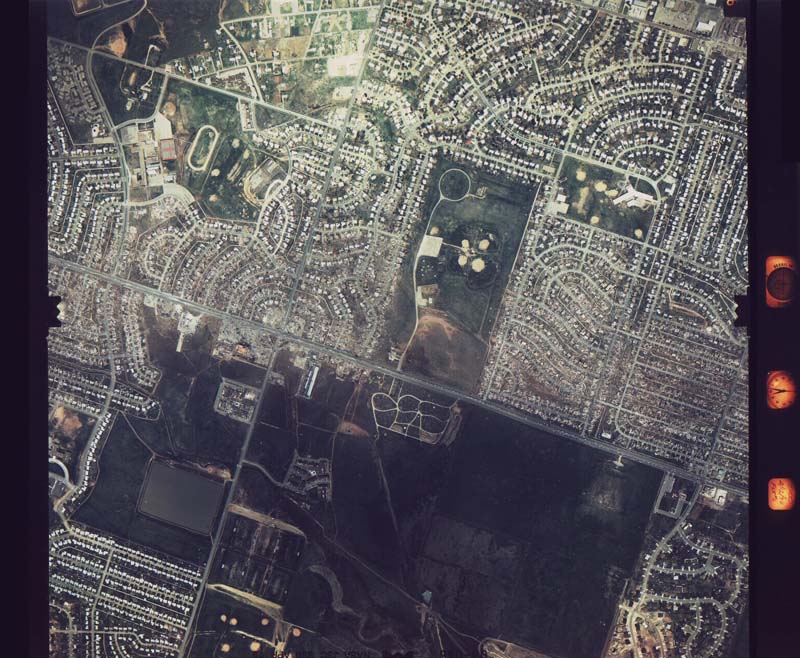

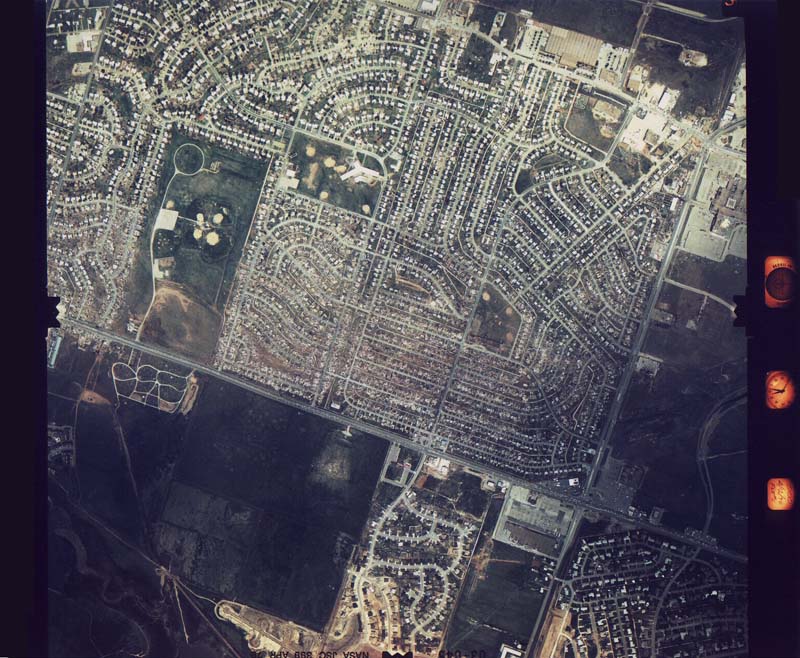

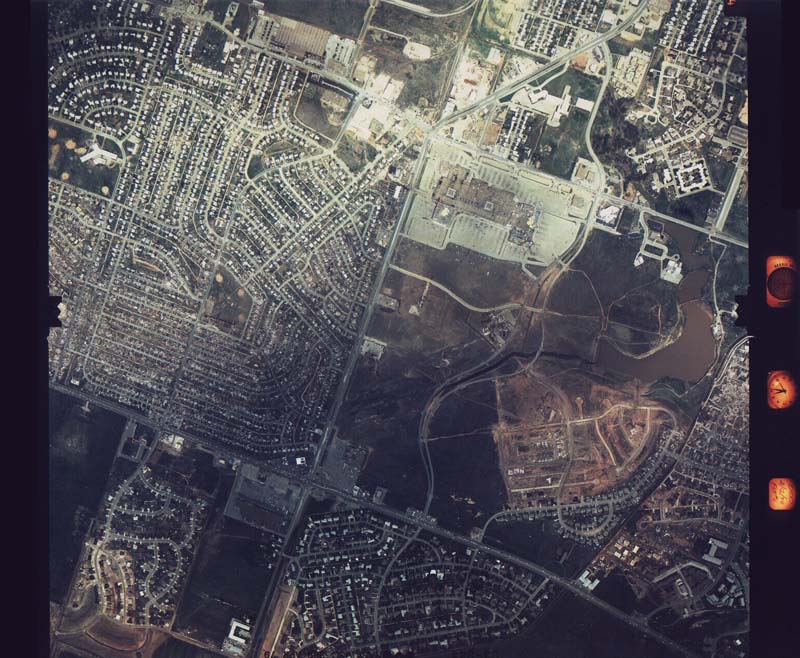

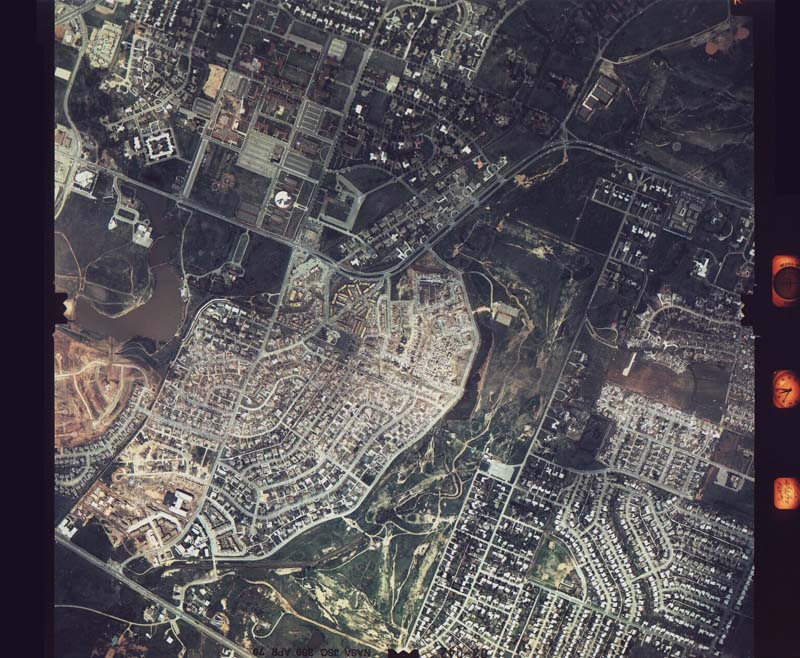

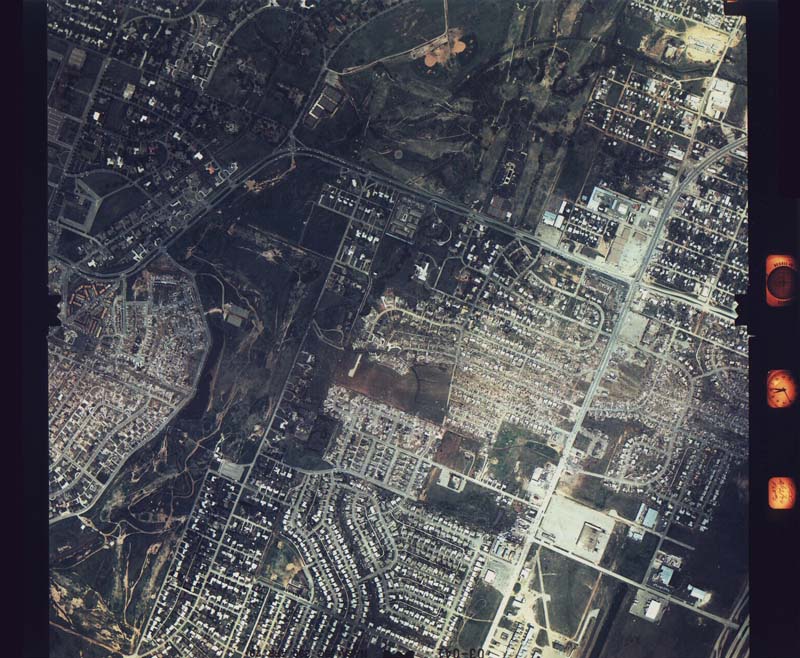

The wide swath of damage can also be seen by viewing the NASA aerial photographs (aerial photos 1-10 on the damage photo tab) and the other aerial photographs (photos 7 & 8 on the damage photo tab). The width of the F1 damage was generally as wide as one mile, and the extent of the F0 damage was even wider, but so widespread that it was not mapped. Strong inflow winds associated with the tornado and the larger-scale mesocyclonic winds rotating around the tornado produced light damage over almost all of the city.

There was much scientific discussion and debate concerning the possibility that the some of the damage was severe enough, and wind speeds high enough, for the tornado to be rated F5. The two worst damage points appeared to be McNiel Junior High (location #1 on the damage path diagram; photos 9-15 on the damage photo tab) and the Southwest National Bank (location #4; no close-up photographs available). After extensive engineering analysis of the winds necessary to produce the observed structural failure to those buildings, it was concluded that all of the damage could have been produced by winds in the upper part of the F4 range (230 - 260 mph). Thus, the tornado damage/intensity was officially rated as a strong F4 tornado.

1. Tornado warning and preparedness systems are worth the time and effort it takes to maintain them. All who have looked at and studied the event agree that the death toll would have been much larger had there not been not been such systems in place and functioning on April 10.

2. Vehicles (cars, pickups, and trucks) are poor protection and should be avoided during tornado situations in larger cities where travel is congested and tornado escape routes are not readily available and open for use. The majority of the fatalities were in vehicles, and a number of those victims left homes that were undamaged by the tornado only to be caught in its deadly path as they tried to flee.

3. Well-built modern houses, in general, offer fairly good protection from tornadoes. Some or all of the walls remained for well-built homes (photos 4-6 on the damage photo tab) and bathrooms in particular provided good protection. Although roughly 4,000 homes were struck by the tornado, there were only five fatalities of people inside homes along the path of the tornado. Many of the 1,800 injured, however, were in homes. This means that those people who moved to the center part of their houses, got down low, and covered themselves, by-in-large escaped with their lives, sustaining injuries instead of death.

4. Even though lesson #3 (above) is true in a violent tornado, the only complete guarantee of safety comes from an underground shelter, an above-ground shelter, or an extremely strongly-built building. McNiel Junior High, a new concrete/steel-reinforced building was not built well enough to provide safe shelter from the tornado. The Southwest National Bank Building was totally destroyed except for its concrete vault, a proxy for an above-ground shelter.

5. As bad as the tornado was, it could have been worse. If McNiel Junior High had been fully occupied by students and teachers at the time of the tornado, there would have been hundreds of additional casualties and many more deaths. Very large groups of people gathered in tornado-vulnerable places, such as schools, stadiums (such as Memorial Stadium), and outdoor events, are disasters waiting to happen. Every year in the United States the threat of a catastrophe looms whenever tornadoes approach large gatherings of people. Fortunately, on April 10, 1979, McNiel Junior High was almost totally unoccupied when the tornado struck and a worse catastrophe was avoided.

The following text comes from Chapter I of the NOAA Natural Disaster Report 80-1, "The Red River Valley Tornadoes of April 10, 1979."

"To the people of the Red River Valley in Texas and Oklahoma, nothing about the weather appeared unusual during the early hours of April 10, 1979: it was business as usual. But before the day's end, three very large, devastating tornadoes swept across the area leaving scores dead and hundreds injured. Most of the deaths were in Wichita Falls and Vernon, Texas, and Lawton, Oklahoma."

"Early on April 10, NWS forecasters became aware of the threat of severe weather. During the morning, closely monitored air mass movements, temperatures, dew points, and winds had all been shifting towards critical values indicative of severe thunderstorms and potential tornadoes. By noon, all doubt was gone. Forecasters at the National Severe Storms Forecast Center in Kansas City1 had to decide only how soon tornadoes would develop and how large an area would be threatened. Tornado Watch #67 was issued at 1:55 p.m. Central Standard Time (CST)2 calling for tornadoes, large hail, and damaging thunderstorm winds in portions of a 30,000-square-mile area in north central Texas and southwest Oklahoma. Just minutes later all counties included in Watch Area #67 were being alerted through statements by the NWS Forecast Offices (WSFOs) at Fort Worth and Oklahoma City. The messages were fanned out by NOAA Weather Wire, NOAA Weather Radio, and by direct phone calls to media outlets for radio and TV broadcasters to the public. In Wichita Falls, an emergency hotline to key local officials, TV, and radio stations assured rapid and complete local dissemination."

"Storm spotter networks were alerted. Members of the Wichita Falls Repeater Club Weather Spotters manned their pre-planned command post on the NWS Office (WSO) and deployed radio-equipped members to vantage points that assured good observation coverage southwest of the city. Radio and TV stations aired the Tornado Watch so that most people were alerted to the threat and ready for warning messages and sirens that were to come later."

"At Vernon, reports of earlier damage to the southwest of the city had alerted spotters and city officials. For example, the police chief called the city manager out of a meeting with county commissioners. The police chief and county sheriff conferred and dispatched patrol cars to the southwest edge of town to watch for the approaching storm. Sirens blew as the tornado bore down on Vernon. In slightly more than 10 minutes, the tornado passed across the southern tip of the city leaving 11 dead, more than 60 injured, and several hundred homes destroyed or damaged. The police chief and sheriff later said the approaching storm did not look like a normal twister, but appeared as a thick, dark mass of clouds low to the ground and difficult to see because of the heavy rain, hail, and low cloud base."

"The thunderstorm system that produced the Vernon tornado crossed the Red River and left a 50-mile-long skipping track of tornado damage through Oklahoma. Just after 5:00 p.m., another tornado spawned by the same thunderstorm system crashed into Lawton, Oklahoma. Lawton had been alerted by Tornado Watch #67 and had received a tornado warning issued by WSFO Oklahoma City. Lawton was as ready as a community could be for the tornado. Using spotter and radar reports, Lawton officials sounded the siren system to warn the people of the approaching storm. As a result of the early warning, the casualty list of 3 dead and 109 injured was relatively small despite the destruction of several hundred homes and businesses."

"About the time the Vernon tornado was moving across the Red River into Oklahoma, 20 miles to the south another funnel cloud was dropping out of the thunderstorm clouds approaching Harrold, Texas. This thunderstorm spawned a tornado with a continuous ground track of almost 60 miles. Fortunately, its long path on the ground was mostly over open farmland so that it caused relatively few casualties and small total property damage. However, several small communities, among them Harrold, Texas and Grandfield, Oklahoma, were hit by the storm."

"When the giant tornado struck Wichita Falls just before 6:00 p.m., most people were not surprised. Severe weather warnings had been in effect for Wichita County and Wichita Falls for almost an hour. The warnings were being broadcast repeatedly by two local TV stations and three local radio stations which were receiving continuously updated information over the emergency hotline connecting them with the Wichita Falls WSO. The siren system for the city was sounded three times, the last around 5:50 p.m., just as the storm spotters reported the tornado approaching Memorial Stadium in the southwestern suburbs of Wichita Falls. The giant tornado was a massive black column extending from the low striated base of the inky clouds to the ground. Huge pieces of debris thrown high in the air were clearly visible from miles away as the storm cut a swath of destruction through the city. Eyewitnesses described details of the storm differently, but they were unanimous on one point -- it was an awesome, terrifying experience beyond anything they had encountered before."

"Despite excellent warning lead-time and multiple soundings of the sirens, some people of Wichita Falls either did not hear the warnings or failed to take prescribed lifesaving actions. More than 40 died, and about 1,700 were injured. As the storm bore down, those who sought the safest refuge in their immediate surroundings generally fared well. Those who were caught in automobiles and trucks made up a high percentage of the fatalities. People from the shopping center took shelter in refrigerator vaults, in restrooms, and under closets. Several got extra protection by covering themselves with mattresses and pillows. They survived!"

"The three main storms in the Red River Valley outbreak were giant tornadoes. Each lasted for an hour or more and left a continuous track of ground damage 35 miles or longer. In addition, the damage paths of all three were wider than normal. This was especially true of the Wichita Falls tornado, whose more than 1-mile-wide path of damage is one of the biggest on record. T. T. Fujita, noted tornado researcher from the University of Chicago, said, 'The damage path was one of the widest I have ever seen, and its intensity was almost equal to that of the giant storm that leveled Xenia, Ohio, in the 1974 tornado outbreak.'"

"When the day had ended, the tornadoes had left in their wake a tragically high toll -- 56 dead and 1916 injured. According to the American National Red Cross, 7,759 families suffered losses in the storms (Table 1). Losses eligible for Federal disaster relief totaled $63 million, but Federal disaster assistance did not cover additional millions in damages."

1 The Storm Prediction Center is now located in Norman, Oklahoma

2 All times in Central Standard Time

|

Table 1 -- Casualty and Property Losses -

Red River Valley Tornadoes |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| TEXAS | OKLAHOMA | TOTAL | |

| Deaths | 53 | 3 | 56 |

| Injuries | 1,807 | 109 | 1,916 |

| Hospitalized | 240 | 19 | 259 |

| Dwellings | |||

| 2,784 | 150 | 2,934 | |

| 923 | 97 | 1,020 | |

| 1,803 | 440 | 2,243 | |

| Mobile Homes | |||

| 103 | 36 | 139 | |

| 1 | 4 | 5 | |

| Apartment/Condominium | |||

| 1,124 | 8 | 1,132 | |

| 0 | 4 | 4 | |

| 170 | 0 | 70 | |

| Small Businesses | |||

| Major Damage | 98 | 14 | 112 |

| Families Suffering Losses | 7,006 | 753 | 7,759 |

| These figures include 12 counties. In Texas: Clay, Foard, Wichita and Wilbarger; and in Oklahoma: Carter, Cleveland, Comanche, Cotton, Jefferson, Pottawatomie, Stephens and Tillman. Casualty data were supplied by the Texas and Oklahoma NWS offices. Other data were supplied by the American National Red Cross. | |||

The following text contains excerpts from the Texas Department of Water Resources publication "A Review of Texas' Weather in 1979: The Year of Devastating Tornadoes and Flash Floods" published in 1980. The publication was written and prepared by George W. Bomar of Weather Modification & Technology Section of the Texas Department of Water Resources.

From the blizzards that traditionally pound the Panhandle each winter to the enduring heat that scorches vast sections of Texas later in the summer, Texas in the meteorological sense truly is the "Land of Contrast." Perennially the State perseveres through frequent bombardments of hail, high winds, and flash floods, often with the accompaniment of tornadoes-as well as the threat of being struck on its coastal flank by a hurricane or intense tropical cyclone.

Inevitably each year some sector of Texas suffers from the effects of a tornado strike, a blinding snowstorm, a violent hail-bearing thunderstorm, or a raging sand- or dust storm. In many years at least some portions of the Lone Star State experience destruction or severe damage from an untimely freeze, a debilitating drought, or a lengthy spell of excessive rains. Assuredly, no two years weatherwise in Texas are even remotely similar, for the community that reeled one year from a capricious dry spell likely is the recipient of plenty of rain in the following year, while a not-too-distant neighboring locale that hurt from a disastrous hailstorm one Spring experiences relative calm during the following year's storm season.

Very often, those features of Texas weather having the most import-such as the continuation or cessation of damaging drought, occurrences of flash-flooding rains, sharp changes in temperature, and incidences of tornadoes and hurricanes, cannot be discerned from the volumes of meteorological data that are published periodically. This report is an attempt to describe thoroughly but concisely the noteworthy elements of the Texas weather scene throughout 1979.

An explanation of both the causes and effects of the many and varied weather systems that affected Texans during the year has been the central objective of this endeavor. In addition, the author hopes that the analyses will serve as a handy source of reference to those who seek to recall the past and those whose research work attempts to relate the weather to other aspects of human existence.

Those sources of meteorological data used in this report consist of: official rainfall, snowfall, temperature, wind, sunshine, and moisture data as provided by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in the publications, "Climatological Data: Texas," "Local Climatological Data" (for selected cities), "Storm Data, and "Daily Weather Maps;" weather teletype reports (circuits "A" and "C") from the National Weather Service surface and upper-air observing network; surface and upper-air facsimile charts provided by the National Meteorological Center of NOAA; newspaper accounts; and photographic data obtained by the author.

Rampaging killer tornadoes and devastating floodwaters brought unparalleled tragedy to groups of communities in the Low Rolling Plains and the Upper Coast of Texas during April. The deadliest tornadoes to strike in Texas in 26 years ravaged parts of four communities near the Red River on April 10, taking 53 lives, injuring 1808, and causing damage worth $427 million1.

Barely one week later, phenomenally great amounts of rainfall poured on the southeastern sector of the State, taking 4 lives and inundating parts of numerous communities. Numerous other disruptive weather events, including torrential, flash-flooding rains, scattered but frequent incidents of hail, and a widespread dust and sand storm, highlighted April, an unusually wet but seasonably mild month for most Texans.

A very intense spring storm shifted out of the Rocky Mountains on April 10, generating lines of severe thunderstorms that swept across the northern portion of the State. One group of violent thunderstorms roared across the northern Low Rolling Plains late that afternoon and spawned a series of tornadoes that ripped through four Texas communities.

One of the tornadoes, having a width that varied from 1/2 to 1 1/2 miles, cut a swath of devastation across the southern sector of Wichita Falls in less than 30 minutes, killing 42 persons, injuring more than 1700, and burying dozens of city blocks under tons of debris. A few hours earlier that day, another tornado tore through Vernon, killing 10 residents and injuring more than 60 others. Still other tornadoes struck the communities of Lockett and Seymour a short time later, killing one inhabitant in Lockett.

1 A tornado struck Waco and McLennan County on May 11, 1953, inflicting 114 deaths, 597 injuries, and damages of $4i.2 million. The most recent exceptionally destructive storm to hit the Wichita Falls area occurred on April 3, 1964, when a tornado killed 7 people, injured 111, and caused $15 million in damages, including 225 homes that were completely destroyed.

The killer tornadoes that ravaged parts of three Texas communities near the Red River late in the afternoon stemmed from a wave of very intense thunderstorms that developed shortly after noon when a dry line advanced rapidly eastward out of the High Plains ahead of an approaching Pacific cold front. Earlier in the day around daybreak, low-level moisture from the Gulf was observed pouring northward through the heart of the State while much drier air was surging eastward across the Pecos River (Figure 10).

Other ingredients for a volatile weather situation were also present: a major upper-air trough extending from the southern Rockies into northern Mexico, migrating eastward into western Texas and deepening significantly at the same time (Figure 11); a strong wind shear from the surface to 500 millibars and a thin layer of very moist air at the surface with rapid drying immediately above at about 700 mb (Figure 12 and Figure 13).

The atmosphere in the Low Rolling Plains was highly unstable (with a Totals Index above 50 and a strong positive K Index extending southward out of western Oklahoma); very vigorous lifting of such unsettled air by the advancing dry line seemed sure to trigger violence (Figure 14). With surface pressures in the southern High Plains plunging rapidly, a low pressure center formed in the vicinity of Lubbock around noon (Figure 15).

As the much drier air whipped eastward out of the southern High Plains just after noon, thunderstorms, some of which were very heavy, boiled up in parts of the eastern High Plains and quickly spilled over into the Low Rolling Plains. A few intense thunderstorms erupted at about the same time in the northwestern portion of North Central Texas; small hail and high winds raked Gainesville and Decatur during the noon hour. Soon thereafter tornadoes were spotted near Crosby ton and Plainview and golfball size hail fell near Tulia, Afton, and Washburn (High Plains).

Meanwhile, strong gusty winds associated with the eastward progression of an intensifying upper atmospheric storm out of New Mexico made travel hazardous in. much of the Trans-Pecos region. Winds gusted the 93 miles per hour (mph) in Guadalupe Mountain National Park at mid-afternoon, while wind gusts of 60 mph or more stirred up dust and sand that reduced visibilities at many points from El Paso to Midland to 3 miles; at Lubbock visibilities dropped to 1 1/2 miles by late afternoon.

By mid-afternoon the surface low had migrated northeastward toward the northern Low Rolling Plains, where steep pressure falls of up to 8mb or more in three hours were observed (Figure 16 insert). While the leading edge of the moist, tropical air had already surged northward across the Red River, giving Wichita Falls a vigorous southeasterly wind and a climbing dew point (Figure 16), the advancing edge of much drier, continental air swept eastward out of the High Plains and undercut the less dense and more moist tropical air. Childress lay in the path of the advancing low pressure center, as surface pressure fell drastically and winds backed during the afternoon before the much drier continental air enveloped the region in the evening (Figure 17).

The effects of passage of both the warm front from the Gulf and later the dry line from the west were pronounced at points like Abilene, where rapidly falling surface pressures, a soaring temperature, and a sudden plunge in dew point (signaling the arrival of the dry line) identified well the events that combined to cause devastation farther to the north a few hours later (Figure 18).

Why the Red River Valley between Childress and Bowie received the most severe outbreak of thunderstorms is explained by Figures 19-26. The most active portion of the advancing dry line traversed this sector of the Low Rolling Plains at precisely the time of occurrence of the tornado outbreak (Figure 19). A sharp temperature gradient immediately preceded the movement of the drier air into the region at 850 mb (Figure 20), while at 700 mb the axis of maximum winds was positioned directly overhead the upper Red River valley (Figure 21) and appreciable vertical motion was evident (Figure 22).

At about the mid-point in the atmosphere (around 500 mb), significant cold air advection occurred, thus exacerbating unsettled conditions, already present (Figure 23). The highly unsettled atmosphere out ahead of the advancing dry air is illustrated by the sounding taken at Stephenville just as the gargantuan tornado was hitting Wichita Falls; the lowest 300 mb of the atmosphere was highly convectively unstable (Figure 24).

Stability indices indicated the air throughout central. Texas was extremely unstable early in the evening (Figure 25). Meanwhile, behind the dry line and cool front in the High Plains, the atmosphere quickly stabilized, and drying out was evident in the lower half of the atmosphere below 500 mb (Figure 26).

Numerous other thunderstorms trekked across the area between Abilene, Wichita Falls, and Brownwood during the early evening, as the surface front, now occluded in the Panhandle, pushed relentlessly eastward. For the most part, however, rainfall amounts were modest, with only a few points collecting more than 1 inch (Figure 27).

By dusk a strong of new, very intense thunderstorms formed farther south in Texas. This line raced northeastward, spilling heavy rains, hail and high winds on numerous communities. A thunderstorm that pelted the Coleman area with golfball-size hail also generated a tornado that caused considerable damage to power lines and outbuildings north of the city. A second severe thunderstorm pounded the area just north of Brownwood with hail having a diameter of 3 to 3 1/2 inches.

Violent weather became more widespread as the afternoon progressed. The first in a series of tornadoes struck near Foard City shortly after 3 o'clock destroying several rural homes, barns, and farm equipment. Then, a second vicious tornado formed near Thalia and moved into Lockett, where a driver of an auto was killed when her vehicle was thrown 200 yards off the highway.

A short time later, the same tornado invaded Vernon, taking the lives of 10 inhabitants and injuring 67 others. The Vernon tornado destroyed a restaurant, motel, a farm implement store, and more than a dozen homes; damage totaled $27 million. Half of the injuries sustained by Vernon residents were deemed critical by city officials. Another tornado swept the community of Harrold soon thereafter, causing much less extensive damage. The thunderstorm that fostered that tornado also produced hail up to 3 inches in diameter west of Harrold.

A fourth tornado touched down just outside of Seymour an hour later, but again damage was comparatively minor. The huge thunderstorm that yielded the Seymour tornado also pounded Holliday with baseball-size hail and an area west of Iowa Park with golfball-size hail.

The most devastating tornado of the day dipped from a thunderstorm (with a top estimated at 58,000 feet) that was moving northeastward into Wichita Falls at a speed of 35 miles per hour a few minutes before 6:00. Within 30 minutes the tornado, with a track that varied between 1/2 and 1 1/2 miles wide and 8 miles long, had sped across the southern portion of Wichita Falls.

Forty-two people were killed outright by the storm, while 3 others died of heart attacks. Twenty-five of the deaths were. auto-related; 16 of that total died while in their autos trying to flee the storm, and 11 of that number abandoned homes not touched by the tornado.

Three thousand and 95 homes were destroyed while roofs of many other buildings were sheared away. More than 1700 injuries occurred within Wichita Falls. One thousand and 62 apartment units and condominiums were destroyed, and 93 mobile homes were demolished. Wrecked cars were smashed against bridge abutments, a power plant was knocked out, and part of a high school was destroyed.

Total damage in the city was estimated at $400 million; five thousand families (or about 20,000 people) were left homeless. This most damaging tornado in Texas history was not finished, however. It sped into Clay County, causing no deaths but 40 injuries and damage in the communities of Dean and Petrolia that amounted to $15 million. Golfball-size hail fell prior to and immediately after the tornado passed along a track that took it into Oklahoma (where it dissipated near Waurika).

Following the deadly Red River Valley tornado outbreak, the National Weather Service, in partnership with FEMA and the American Red Cross, produced a documentary called "Terrible Tuesday" that chronicled the events in Wichita Falls on April 10, 1979. The video includes survivor accounts and safety information. It was produced in 1984 and has a run time of 19 minutes, 30 seconds.

The Terrible Tuesday video can be viewed via the NWS Norman YouTube Channel or below.

|

The Harrold tornado was in its formative stages at about the time the Vernon tornado was crossing the Red River. First indications of tornado damage were near Harrold, which is located approximately 16 miles southwest of Vernon. Two Oklahoma University meteorology students (including Wayne Collamore) photographed the large tornado, which descended from a rotating wall cloud under the southwest flank of the severe thunderstorm. The tornado moved across Highway 287 and caused light damage before entering Wichita County about 5 miles northeast of Harrold. Additional light rural damage occurred in the miles of Wichita County that the tornado covered. The half-mile wide tornado crossed the Red River into Oklahoma about 9 miles north-northeast of Electra. The path length was 9 miles in Texas and 55 miles in Oklahoma. At about the time the tornado was developing at Harrold, 1.5 to 3 inch diameter hailstones were reported 7 miles west of Harrold. |

|

Approaching Harrold, Texas from the southeast on Highway 287 - view is looking west at 4:00 pm CST. © Wayne Collamore |

Approaching Harrold, Texas from the southeast on Highway 287 - view is looking west at about 4:05 pm CST. Fifty mph sustained inflow winds were occurring at this time. © Wayne Collamore |

Approaching Harrold, Texas from the southeast on Highway 287 - view is looking west at about 4:05 pm CST. © Wayne Collamore |

Approaching Harrold, Texas from the southeast on Highway 287 - view is looking west at about 4:05 pm CST. © Wayne Collamore |

View looking west just east of Harrold on Highway 320 at about 4:15 pm CST. © Wayne Collamore |

View looking west just east of Harrold on Highway 320 at about 4:15 pm CST. © Wayne Collamore |

View looking west about 3-4 miles east of Harrold on Highway 320 at about 4:15 pm CST. © Wayne Collamore |

View looking west about 3-4 miles east of Harrold on Highway 320 at about 4:15 pm CST. © Wayne Collamore |

View looking northwest east of Harrold on Highway 320 at about 4:20 pm CST. © Wayne Collamore |

|

|

The tornado developed on the extreme northeast side of Seymour and moved northeast to about 2 miles north-northeast of Maybelle. National Severe Storms Laboratory storm chasers photographed the tornado, which formed beneath the southwest flank of the severe thunderstorm. The storm intercept teams noted that the tornado developed from a rotating wall cloud in the Seymour area. Several brief touchdowns in Seymour resulted in scattered roof damage and one overturned truck. After moving northeast of Seymour, the tornado intensified. Photographs indicated that it was a large, cylindrical tornado with a well organized debris cloud. Fortunately, the tornado moved through rural areas and did not affect any housing at this stage. The twister did level a number of telephone poles along Highway 283, before dissipating just east of 283 near Maybelle. Residents of Seymour reported that the tornado was preceded by very heavy rain and hail almost 2 inches in diameter. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The following severe weather account is by Gene Moore. Gene is a graduate of Oklahoma University who photographed storms when he lived in Norman, Oklahoma during the 1970s. He later moved to Oklahoma City where he worked in TV weather before working for the federal government. He is now self-employed and lives with his family in San Antonio, Texas.

The following images and text have been provided by permission of the author are to be used for informational purposes only. The following images and text © copyright Gene Moore unless otherwise indicated.

The spring of 1979 was a very active tornado period for the plains states. The tornadoes pictured here were part of the Red River Valley Outbreak, the biggest event of that year. We left NSSL in Norman, Oklahoma at 10:30 AM to our target of Vernon, TX. A wind maximum gusting to 65 knots moved over Guadalupe Peak recording station in far southwest Texas; this triggered our departure. There we hoped the dryline and warm front would intersect with a strong jet stream. As we drove south on the H.E. Bailey Turnpike to Lawton we were in low clouds with light fog and drizzle. My chase partner for the day was Eddie Sims who had chased for years with Jim Leonard. He was great at identifying cloud structures.

Our path across the Red River was always through Lawton; then we usually took a short cut on OK 36 and OK 5 through open wheat country to Fredrick and Vernon. For the first time in years we altered that route. Instead of going through Vernon we dropped further south through Seymour, then north on Texas 267. We knew the storms were coming, but didn't want to meet fast moving cells head-on in the low visibilities north of the warm front. As it turned out we would have driven into Vernon just before a major tragedy unfolded with injuries and death. Would we have seen the tornado and diverted? I can't say for sure, chasing was different back then. We didn't get phone guidance and it was before on-board equipment. We were on our own.

By the end of the day we had seen four tornadoes, Thalia, Vernon (although not well), Lake Kemp, and Seymour. Thanks to Bob Davies-Jones from NSSL we saw another tornado as the storm moved into Wichita Falls. It was a large, but distant funnel that may have been the beginning of the horrific tornado that moved through that city. We couldn't make it into Wichita Falls because we almost ran out of gas. The electrical power to local stations was down from the storm which prevented the gas pumps from operating and us from getting more gas.

If I had the opportunity to chase this one over I certainly would do it differently, but considering we were on visual back then we didn't do too bad. This was the most spectacular event I had ever witnessed to date. Only three times in my chase career have I seen vertical storm tower velocities this strong. The other times were outbreaks on June 8, 1974 and May 3, 1999.

Driving north on Texas 267 we witnessed the Thalia tornado. Further to the northeast we could see a very large tornado with reddish suction spots rotating about the circulation. We think this was the early stages of the Vernon tornado. As we drove northeast on US 70, debris was still falling to the ground. A mattress fell beside the vehicle and I looked out to see a woman standing in what appeared to be a junk yard. It was the remains of her home. There were scattered remains of destroyed structures on either side of the road. The damage was quite hit and miss.

After dodging power lines, broken poles, and busted trees we dropped south on US 183/283 on the east side of Vernon. The trees on the southwest edge of the city were denuded of limbs and bark. Had we gotten stuck in the damage of the town the chase would have been over. To avoid getting trapped, it's been my policy to avoid blasted cities when ever possible.

We continued south passing a damage path across the highway from the Harrold tornado. That supercell was in progress just to our northeast, although there was no direct route to catch the fast moving storm. It was spectacular to watch! All the storms this day exhibited violent cloud motions. The clouds in the flanking lines exploded up the back of the storm through the back-sheared anvil to the overshooting top. The clouds would roll over like they were collapsing into a deep hold. I had never witnessed anything of this magnitude.

We proceeded southwest toward Seymour witnessing a small tornado near Lake Kemp that was accompanied by golf ball size hail. This storm appeared insignificant compared to what we had seen so we drifted southwest in search of something better. A storm appeared on the horizon that had developed far to our south near Abilene. It looked killer from the beginning. By this time teams from NSSL and the University of Oklahoma had arrived.

The late afternoon lighting was much different on this storm giving a yellowish cast as we looked southwest. The tornado was coming down, but getting photography was difficult. We were rushed to get into position. During this time I navigated and Eddie drove. He shot these images one handed while driving down a dirt road. I'm surprised he got the tornado in the frame.

We were under an extensive rain free updraft area on the southeast side of the storm. Precipitation was to our west through southwest and wrapped around the tornado. We were worried that the rain would get worse before we set up the cameras which was not desirable considering we were on a dirt road. At this time the tornado was just getting planted well to our southwest. A darker version of this image shows the rain curtain extending around the vortex.

Usually hail is a problem in this position, but we encountered none on this storm. Stones as large as two inches were reported further to our northeast. We continued to drive east on a dirt road from Mabelle, Texas which is basically an intersection with a couple of old buildings. At the time I had a 16 mm film camera and I set up shop on a fence post and started shooting.

This image was taken as the tornado widened and approached our position. The powerful vortex, although rated only F-2, had winds of over 200 MPH. as derived from photogrammetric analysis. It was on the ground for 11 miles.

Rain was beginning to rotate totally around the funnel at this time and the tornado was producing an audible roar so loud it was hard to communicate. While photographing this shot I began to feel vibration in the camera. I had a good full frame shot of the suction spots rotating about the base of the funnel. I didn't want to move. Eddie was trying to tell me something; finally with some tugging, he got my attention. The tornado was at the top of the hill less than a mile away. It was roaring down the hill fairly fast and my chase partner was concerned that we couldn't get out of the path.

We decided to make a break for it to the east which was not a smart move. This route took us in front of the advancing vortex and provided a pretty exciting ride. At the time we passed in front of the funnel the mud road had become slick enough that the car was not going very fast anymore. During this time I was trying to shoot pictures through the window. The tornado slung mud across the inside of the windshield which made it difficult to drive. Eddie complained, but kept fighting the wheel. As the tornado neared the road it began to shrink in size and slowed a little, aiding our hasty retreat. We sat up to photograph to the east of the tornado and shot back west and north as it passed.

The funnel was quite close at this time and large black crows were caught up in the outer circulation. They were flying by faster than I thought any bird could go; I wonder what they thought... After this scene the tornado became wrapped in the rain and difficult to photograph.

A killer tornado, which spread death and destruction through Wilbarger County and the city of Vernon during the mid afternoon on Tuesday, April 10, 1979, is pictured here as it formed near the Five-In-One Community. The twister, which had a wide funnel, shrouded the community in darkness as it swept eastward south of Vernon and along the east side of the city, resulting in millions of dollars in damage and 11 directly killed by the tornado (10 in Vernon and 1 in Lockett, TX).

Wichita Falls Tornado - Wolfgang LangeThe formation of the tornado and its movement toward the Memorial Stadium and McNiel Junior High School were captured by Wolfgang Lange from the front of his apartment complex which was across the street from school building (Tornado Track Figure; Location #2). After taking his last picture of the approaching tornado, Mr. Lange retreated to the apartment complex laundry room and hid between heavy commercial washers and dryers, escaping with only minor injuries. |

|

View looking west-northwest near Memorial Stadium in Wichita Falls, Texas at wall cloud on the southwestern edge of the thunderstorm. © Wolfgang Lange |

View looking southwest near Memorial Stadium in Wichita Falls, Texas at wall cloud on the southwestern edge of the thunderstorm. McNiel Junior High School is shown in the middle left of this and all of the following photos. The school building was totally destroyed by the tornado. © Wolfgang Lange |

View looking southwest near Memorial Stadium in Wichita Falls, Texas at the time of tornado touchdown. © Wolfgang Lange |

View looking southwest near Memorial Stadium in Wichita Falls, Texas at the approaching tornado. © Wolfgang Lange |

View looking southwest near Memorial Stadium in Wichita Falls, Texas at the approaching tornado. © Wolfgang Lange |

View looking southwest near Memorial Stadium in Wichita Falls, Texas at the approaching tornado. |

View looking southwest near Memorial Stadium in Wichita Falls, Texas at the approaching tornado. © Wolfgang Lange |

View looking southwest near Memorial Stadium in Wichita Falls, Texas at the approaching tornado. © Wolfgang Lange |

View looking southwest near Memorial Stadium in Wichita Falls, Texas at approaching tornado. © Wolfgang Lange |

View looking southwest near Memorial Stadium in Wichita Falls, Texas at the approaching tornado. © Wolfgang Lange |

Wichita Falls Tornado - Robert MoletOn the first street of houses to the northeast of Wolfgang Lange's apartment complex, Robert Molet also photographed the approaching tornado (Tornado Track Figure; Location #3). Unlike Mr. Lange, Mr. Molet did not have an unobstructed view of the western horizon and did not immediately recognize that the threatening cloud was a tornado. Thus, he stood in his backyard driveway and photographed the destruction of the apartment complex and the beginning of destruction in his neighborhood. Mr. Molet continued to take photographs until the wind blew him into his garage. Although his house was completely destroyed, Mr. Molet escaped with only minor injuries as his pickup truck was blown over him, protecting him from the worst winds and debris. The tornado's first fatalities were recorded in the apartment complex and adjoining housing area. |

|

View looking southwest near Memorial Stadium in Wichita Falls, Texas at the approaching tornado. © Robert Molet |

View looking southwest near Memorial Stadium in Wichita Falls, Texas at the approaching tornado. © Robert Molet |

View looking southwest near Memorial Stadium in Wichita Falls, Texas at the approaching tornado. © Robert Molet |

View looking southwest near Memorial Stadium in Wichita Falls, Texas at the approaching tornado. © Robert Molet |

View looking southwest near Memorial Stadium in Wichita Falls, Texas at the approaching tornado. © Robert Molet |

View looking southwest near Memorial Stadium in Wichita Falls, Texas at the approaching tornado. © Robert Molet |

Wichita Falls Tornado - Pat BlacklockThe tornado was photographed from the south during this period by Pat Blacklock, who was located on the southern shore of Lake Wichita (Tornado Track Figure; location #5). In the latter Blacklock photographs, the gust front and associated strong west winds to the south of the tornado can be seen producing waves on Lake Wichita and kicking up spray from the lake. |

|

View looking west-northwest from south shore of Lake Wichita at the tornado approaching Wichita Falls, Texas. © Pat Blacklock |

View looking west-northwest from south shore of Lake Wichita at the tornado approaching Wichita Falls, Texas. © Pat Blacklock |

View looking northwest from south shore of Lake Wichita at the tornado approaching Wichita Falls, Texas. © Pat Blacklock |

View looking northwest from south shore of Lake Wichita at the tornado approaching Wichita Falls, Texas. © Pat Blacklock |

View looking northwest from south shore of Lake Wichita at the tornado approaching Wichita Falls, Texas. © Pat Blacklock |

View looking north-northwest from south shore of Lake Wichita at the tornado approaching Wichita Falls, Texas. © Pat Blacklock |

View looking north from south shore of Lake Wichita at the tornado approaching Wichita Falls, Texas. The tornado has widened and intensified at this stage. © Pat Blacklock |

View looking north from south shore of Lake Wichita at the tornado approaching Wichita Falls, Texas. The tornado has widened and intensified at this stage. © Pat Blacklock |

Wichita Falls Tornado -

|

|

View looking west-southwest at the approaching tornado from Ligon Coliseum at Midwestern State University in Wichita Falls, Texas. © Joe Henderson |

View looking west-southwest at the approaching tornado from Ligon Coliseum at Midwestern State University in Wichita Falls, Texas. © Joe Henderson |

View looking west-southwest at the approaching tornado from Ligon Coliseum at Midwestern State University in Wichita Falls, Texas. © Joe Henderson |

View looking west-southwest at the approaching tornado from Ligon Coliseum at Midwestern State University in Wichita Falls, Texas. © Joe Henderson |

View looking west-southwest at the approaching tornado from Ligon Coliseum at Midwestern State University in Wichita Falls, Texas. © Joe Henderson |

View looking west-southwest at the approaching tornado from Ligon Coliseum at Midwestern State University in Wichita Falls, Texas. © Joe Henderson |

View looking southwest at the approaching tornado from the roof of Bethania Hospital in Wichita Falls, Texas. © Troy Glover |

|

Wichita Falls Tornado - Winston WellsAfter the tornado left Wichita Falls and travelled northeast, it entered Clay County and changed its appearance. As seen in the photographs by Winston Wells (Tornado Track Figure; Location #10), the tornado became multi-vortex, displaying as many as five satellite vortices rotating around the center of circulation. In this stage, the tornado did extensive damage just south of Dean and near Byars, destroying a large number of rural homes, but causing no more fatalities. |

|

View looking southwest at the approaching tornado northeast of Wichita Falls, Texas. © Winston Wells |

View looking southwest at the approaching tornado northeast of Wichita Falls, Texas. Multiple vortices are seen in this photo. © Winston Wells |

View looking southwest at the approaching tornado northeast of Wichita Falls, Texas. Multiple vortices are seen in this photo. © Winston Wells |

View looking southwest at the approaching tornado northeast of Wichita Falls, Texas. Multiple vortices are seen in this photo. © Winston Wells |

View looking southwest at the approaching tornado northeast of Wichita Falls, Texas. © Winston Wells |

View looking southwest at the approaching tornado northeast of Wichita Falls, Texas. Multiple vortices are seen in this photo. © Winston Wells |

View looking southwest at the approaching tornado northeast of Wichita Falls, Texas. © Winston Wells |

|

| 6 PM CST, 4/09/1979 |

Surface | 850 mb | 500 mb | 200 mb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 AM CST, 4/10/1979 |

Surface | 850 mb | 500 mb | 200 mb |

Black and white image of radar echoes from the NSSL 10 cm Doppler radar in Norman at 2340Z, April 10, 1979. Credit: NSSL |

Photo of a TV screen showing the radar reflectivity display of the approaching Wichita Falls supercell. Time is approximate 2330-2340Z, April 10, 1979. Credit: © Doug Peterson |

Map of Radar Reflectivity and Mesocyclone Positions of the Wichita Falls, Texas Supercell at 2330Z, April 10, 1979. Credit: Don Burgess |

Map of Radar Reflectivity and Mesocyclone Positions of the Wichita Falls, Texas Supercell at 0000Z, April 11, 1979. Credit: Don Burgess |

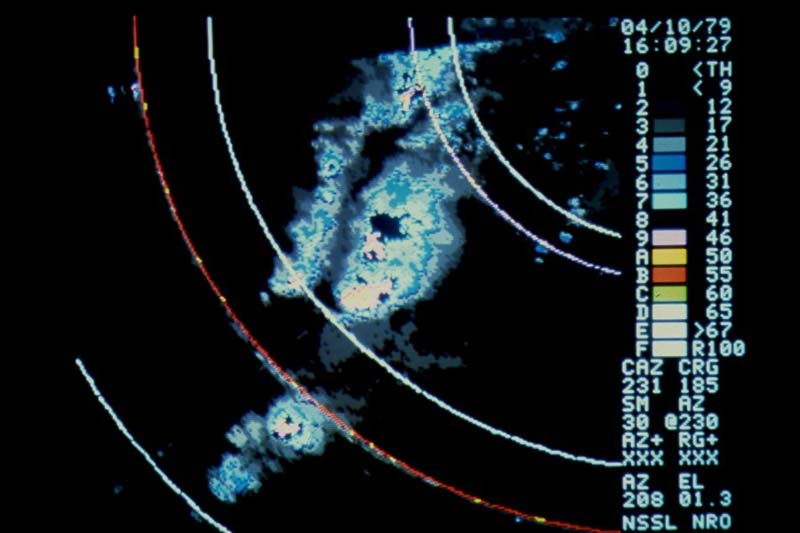

Color image of radar reflectivity values from the NSSL 10 cm Doppler radar in Norman at 2155Z, April 10, 1979. Credit: NSSL |

Color image of radar velocity values from the NSSL 10 cm Doppler radar in Norman at 2155Z, April 10, 1979. Note: warm colors indicate outbound velocities and cool colors indicate inbound velocities. Credit: NSSL |

Color image of radar reflectivity values from the NSSL 10 cm Doppler radar in Norman at 2209Z, April 10, 1979. Credit: NSSL |

Color image of radar velocity values from the NSSL 10 cm Doppler radar in Norman at 2209Z, April 10, 1979. Credit: NSSL |

Color image of radar reflectivity values from the NSSL 10 cm Doppler radar in Norman at 2216Z, April 10, 1979. Credit: NSSL |

Color image of radar velocity values from the NSSL 10 cm Doppler radar in Norman at 2216Z, April 10, 1979. Credit: NSSL |

Color image of radar reflectivity values from the NSSL 10 cm Doppler radar in Norman at 2309Z, April 10, 1979. Credit: NSSL |

Color image of radar velocity values from the NSSL 10 cm Doppler radar in Norman at 2309Z, April 10, 1979. Credit: NSSL |

Color image of radar reflectivity values from the NSSL 10 cm Doppler radar in Norman at 2322Z, April 10, 1979. Credit: NSSL |

Color image of radar velocity values from the NSSL 10 cm Doppler radar in Norman at 2322Z, April 10, 1979. Credit: NSSL |

Aerial Photo #1 |

Aerial Photo #2 |

Aerial Photo #3 |

Aerial Photo #4 |

Aerial Photo #5 |

Aerial Photo #6 |

Aerial Photo #7 |

Aerial Photo #8 |

Aerial Photo #9 |

Aerial Photo #10 |