Heavy to excessive rainfall across parts of central Texas into southern New Mexico may bring areas of flooding into this evening. Excessive runoff may result in flooding of rivers, creeks, streams, and other low-lying and flood-prone locations. Hot temperatures are forecast for the far southwest U.S., parts of California, and the interior northwest U.S. this week. Read More >

On Wednesday May 10th, 1905, the Oklahoma Territory was struck by one of the worst natural disasters in early American history. Tornadoes pounded the southwest part of the Territory, one of which flattened the town of Snyder. The “official” death toll is listed today as 97, but the actual number of victims may never be known. One hundred years later, this single tornado remains the second most deadly (at least) in Oklahoma history, and ranks among the 20 most deadly tornadoes in United States history. [1]

To commemorate the one-hundred-year anniversary of this tragic event, the staff of the Norman Forecast Office collected information on the events of May 1905, in an effort to understand exactly what transpired in Snyder and surrounding areas a century ago. We gathered as many newspapers of the time as we could find, along with any other available information sources we could track down.

The end result is this three-part chronicle. In Weather Synopsis, we present what we know (which isn’t very much) about the meteorological conditions that led to the tornado outbreak. The “Cyclone” includes eyewitness accounts of the storm as it bore down on, and eventually tore through, Snyder. It also includes our detailed assessment of the entire damage track of the Snyder tornado, along with a few others that were known to have occurred that day. Finally, the real story of the Snyder tornado is presented in Aftermath. This section is truly the heart of the story, as it describes the human tragedy as recounted directly by those who were a part of it.

After poring through dozens of newspaper articles and other written accounts of the Snyder tornado, several key points emerge.

First, writers of those days had a different style of penning their thoughts than most present-day writers do. Their style of writing and their attention to detail are quite impressive - almost enchanting, in a way. So, our retelling herein is not really a retelling at all, for we will quote liberally from those authors of the early twentieth century. Stated simply, we could not say it any better than they did.

Second, it becomes evident that the horrible tragedy in Snyder was far beyond the ability of even those eloquent writers of the time to describe. But they tried, and in so doing they often offered graphic descriptions of the storm’s aftermath. (Censorship was not an issue back then.) In the interest of decorum, and out of respect for those who suffered from this event, we will forego the graphic details here.

Finally, there is a good side to every story, no matter how tragic. The Snyder tornado is no exception. We found that the true spirit of the Nation’s Heartland was as alive and well back then as it is now. Read Aftermath to see how neighbors helped neighbors, how surrounding communities responded quickly to the call for help, and how a small town, beaten down, picked itself up and put itself back together.

This summary is dedicated to the memory of the victims of the Snyder tornado of 1905, and to those who suffered the loss of friends, families, and loved ones.

Pages for Acknowledgments and Endnotes are also available.

Weather data from the early twentieth century are hard to come by. There were no weather satellites, no radars, no upper-air weather observations, and very few surface weather observations. But from those few surface observations, and other news accounts of the time, a picture emerges which suggests that May 10th was only one in a series of active, stormy days in the Plains in early May 1905.

Another devastating tornado struck the central Plains only two days earlier. The town of Marquette, Kansas was struck just before midnight on Monday, May 8, resulting in 34 deaths. [1] News articles include reports of other tornadoes striking during the afternoon and evening of Tuesday, May 9, just southwest of Gotebo (30 miles north of Snyder), near Ringwood (west of Enid), and even in St. Joseph, Missouri. One article stated, “Cyclones seem to be general this year, evenly divided throughout all the states.” [2]

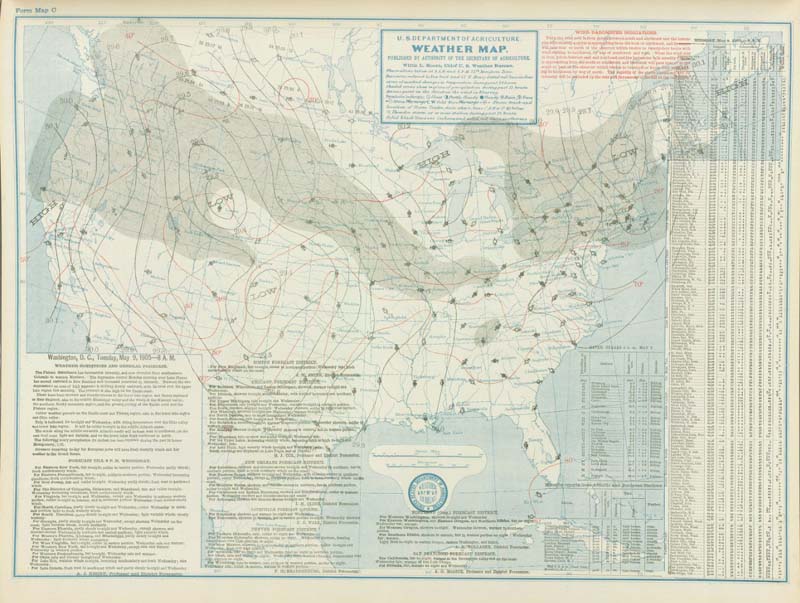

Synoptic weather maps show the general surface weather patterns from North and Central America westward across the Pacific Ocean on the mornings of May 9th, May 10th, and May 11th. [28] (Times are given as 1300 Greenwich Mean Time, or GMT; subtract six hours for Central Standard Time, so the charts are valid at 7 AM CST.) These charts, which were analyzed by hand, show the positions of fronts and other surface weather features. Daily weather maps over the contiguous United States, also valid at 7 AM CST on May 9th, 10th, and 11th, [29] (the listed time of “8 A. M.” is most likely Eastern Standard Time, one hour ahead of CST) provide more detail of pressure and temperature, but do not identify frontal positions.

Focusing attention on the area of the United States, we find a large area of low pressure over the Rocky Mountains on the morning of May 9th,[28] with one center over Wyoming and another over southeastern Colorado. A front can be analyzed from Virginia westward into Nebraska, and most likely is lifting north as a warm front in the central Plains. Early-morning temperatures are near or above 70 south of the front, from Kansas southward. South winds prevail throughout the central and southern Plains, east of the surface low, indicating that moist air is moving north across the area from the Gulf of America. This is still more than 36 hours before the Snyder tornado.

On the following morning, May 10th, [28] we find that a low center has moved to eastern South Dakota, while another has become established over western Colorado. It is at this point that our meteorological knowledge must be called upon to infer what is happening in the upper levels of the atmosphere. Since weather systems generally move from west to east, we conclude that an intense low-pressure trough aloft, which created pressure falls over the Rockies the day before, has moved northeast and caused pressures to fall over the northern Plains. Hence, the low over South Dakota most likely tracked from southeastern Colorado. This weather system likely initiated the tornadoes on May 9th, mentioned earlier as having occurred from Oklahoma to Missouri. But the lingering area of low pressure over Colorado on May 10th implies that another upper-level trough is dropping into the Rockies behind the one that is lifting into the northern Plains. (This trough is known in the weather business as a “kicker,” since it likely kicked the lead trough out into the Plains ahead of it.) Although areas of Kansas and western Oklahoma and Texas are cooler on the morning of the 10th, winds remain south in these areas in response to the new developing area of low pressure to the west. It is likely that this “kicker” trough was the storm system responsible for the tornado outbreak on May 10th, which would level Snyder roughly 14 hours later.

To see what happened next, we must jump ahead momentarily to the next data set, on the morning of May 11th. [28] We find a deep surface low over northern Kansas, a warm front extending eastward and lifting north through the middle Mississippi Valley, and a cold front southward from the low into Oklahoma and Texas. To the south of the warm front, and east of the cold front, south winds are continuing to draw Gulf moisture northward – and most likely have been doing so for most of the past two days.

What happened during the 12 hours or so prior to the Snyder tornado now can be inferred. The low pressure center, which began the day over western Colorado, likely moved to, or reformed over, the central and southern High Plains, around southeastern Colorado or the Oklahoma Panhandle. This is a typical evolution in most Plains-type severe weather outbreaks, and indicates that an intense upper-level disturbance (the “kicker” trough) dove into the central or southern Rockies during the day. South winds increased over Texas and Oklahoma in response to the developing low to the west, drawing warm, moist, unstable air back north into the region. That evening, the disturbance continued eastward and emerged over the Plains, lifting the unstable air and initiating severe thunderstorms.

It is virtually impossible to prepare a smaller-scale meteorological diagnosis of this event based on the available data. So we cannot say why southwest Oklahoma, and Snyder in particular, became the targets of nature’s wrath on that day.

All accounts indicate that the first tornado began in far southwest Oklahoma around 6:45 PM Central Standard Time (CST)[3]. All accounts from Snyder agree that the tornado which hit the town arrived in there sometime between 8 PM and 9:15 PM on the evening of May 10. We can forgive the survivors for not being more precise, as they certainly had more important concerns immediately following the disaster. But the tornado left its own time stamp to indicate its arrival in town. Watches were found in the debris, all stopped within a few minutes of 8:45 PM, and the large wall clock in the Eagle Drug Store in Snyder stopped “at exactly forty-three minutes past eight o’clock”[4]. So we can be reasonably sure that the tornado arrived in Snyder very close to 8:45 PM on Wednesday, May 10th. Sunset occurred in Snyder close to 7:30 PM CST, and twilight faded to full darkness between 8 and 8:30 PM as the storm approached. So we also can be fairly sure that the tornado struck the town after dark. For sure, initial recovery efforts began in full darkness.

There also are varying descriptions of the duration of the storm in Snyder. Some survivors said it lasted a few moments, some said five to ten minutes, some said perhaps fifteen minutes. All agreed that it seemed like an eternity. Knowing what we do about the size of the tornado (damage path one-half mile wide) and its forward speed (30 to 40 MPH), the tornado probably spent less than a minute on any given spot, and traversed the town of Snyder in under three minutes.

According to documentation by the U.S. Weather Bureau’s section director for the Oklahoma Territory (the U.S. Weather Bureau was the predecessor for today’s National Weather Service) and local newspapers, the tornado was first observed about 12 miles west and 9 miles south of Olustee. [5] [6] This initial tornado probably left an intermittent damage path as it curved to the east-southeast and east. The tornado then intensified near the community of Carmel, located 9 miles south and 3 miles west of Olustee. The tornado destroyed a home near Carmel and killed three members of the Hughes family. The tornado grew to about one mile wide as it continued to move northeast, killing the entire family of Frank James and four members of the Ralston family near the community of Lock, which was approximately seven miles south of Altus. The Altus Times reported that “every vestige of a settlement at Lock was swept away.”[7] A number of farmsteads were destroyed and livestock herds were killed near Lock. One of the farms just east of Lock that was destroyed was described as “one of the best improved farms in the county.”[8] The tornado continued northeast and struck the Francis School House which was “scattered over the surrounding country side for miles. Not a stick or stone remains to mark the spot where it stood.”[8] The Francis School House is estimated to have been about 6 miles south and 3 miles east of Altus.

Based on available accounts, the storm underwent a stage of reorganization just after passing Lock and the Francis School House, which led to the formation of a second tornado that would become the Snyder tornado. After destroying the school house, the tornado, “then lifted, and passing eastward crossed the North Fork of the Red River at the mouth of Otter Creek. At the point of crossing the North Fork, it was joined by another tornado which had developed about two miles southeast of the Francis School House. The combined tornadoes then moved rapidly northeastward along the course of Otter Creek…” [5] Another account, based on notes from the chief of the U. S. Signal Station in Oklahoma City, who followed the track of the storm, supports the same evolution: After destroying the Francis School House, “The cyclone then lifted and contented itself with roaring until the mouth of Otter Creek was reached. Here another twister, which had formed some distance south of there and destroyed the Burnett home on the west side of North Fork, united with the one which had come so many miles, and they entered upon a merry waltz up Otter Creek, following up the creek until it takes a turn to the north-west, where it left the creek and began its journey straight northeast across the Prairie for Snyder.” [5]

The formation of a second tornado two miles southeast of the first is very consistent with what is known today as a “cyclic supercell.” The storm initially contained a larger storm-scale circulation (or mesocyclone), from which the first tornado formed. The storm then underwent a cycle in which the mesocyclone center weakened and the tornado dissipated (or “lifted”), while a new mesocyclone center formed a few miles to its southeast and produced another tornado. Knowledge of storm structure and evolution has come a very long way since 1905, and so it is not surprising that observers back then were not at all familiar with the details of what they were seeing happen before them. Cyclic supercells are now known to be present in many tornado outbreaks, often producing a virtual family of tornadoes as each “cycle” results in additional tornadoes following along the same general path of the parent storm. (One of the supercell thunderstorms in Oklahoma on May 3, 1999 produced 20 tornadoes over a six-hour period!)

This second tornado moved east-northeast, crossing the North Fork of the Red River near the mouth of Otter Creek. The tornado then followed very close to Otter Creek, curving to the northeast through what is now northern Tillman County (but was still part of Kiowa County at the time). At least five people were killed southwest of Snyder, including Ray Moss (a tenant at the McCowan ranch), three members of the Engle family, and Mrs. Jack Hunter, who was injured and later died from her injuries. At the Engle home, “The monster again demanded human sacrifices to whet its appetite for the final feast at Snyder.”[5] As the tornado continued northeast, it struck the city of Snyder at around 8:45 P.M. After moving through Snyder, the tornado “kept its northeasterly movement, destroying a couple of small residences within two miles of the townsite, then lifted and caused no further damage.”[5]

One news report indicated that “the same tornado” struck Quinlan (115 miles north of Snyder!), killing three people. [10] Yet another report describes a storm, “that developed in a cyclone and hail storm at Elk City (55 miles northwest of Snyder), two men being killed at or near that town.” [11] These events clearly were not caused by the same thunderstorm that rolled through Snyder, but show that there were other severe thunderstorms across western Oklahoma, and that the storm that struck Snyder and surrounding areas was not the only killer storm in Oklahoma that day.

“Were you ever in a cyclone? If you have had such an experience you will believe the story of the storm without question. If you have not, you will feel inclined to say it’s all bosh. But the following report contains nothing which the editor does not know to be true. The truth is horrible enough without enlarging on it and no one wishes to picture it worse than it is.”

So begins the front-page article in The Snyder Signal Star, dated Friday, May 12, 1905. The headline read, “Most Terrible Storm,” and “Worse Than war – Which is Hell.” Much of the horror depicted in these words relates to the destruction and human toll (see Aftermath), but the article also contains the following account of the storm as it approached, and eventually flattened, Snyder:

Heavy clouds had been hanging in the south-west for some time but they were high and presented no threatening appearance – people freely expressing opinions as to whether or not a rain would come.

A few minutes before 8 o’clock, a fearful roaring was heard in the south-west. The writer remarked to his family that, “but two things ever cause a roar like that – either a very heavy hail storm, or a cyclone.” A few minutes of the fearful roaring and then came a heavy rain fall accompanied by some hail caused a second remark expressing the belief that we were then getting the outer edge of a heavy hail storm which had visited Greer county. In a few minutes the rain ceased and was succeeded by the most terrific electrical storm the writer has ever witnessed. Electricity ran along the telephone wires with a hissing like a sky rocket starting on its upward flight. This lasted probably another fifteen minutes, ceasing as suddenly as it had started, then, after a moments dead lull, the hungry monster broke upon the town picking up strong and well-built buildings and tossing them about like they were bundles of straw, taking away the fragments of one man’s house and leaving in its place pieces of houses which stood blocks away.

Wednesday the 10th day of May was the day. The hour was between 8 and 9 o’clock. Several watches having stopped showing from 14 to 18 minutes before 9 o’clock, it is safe to say that the town was wiped out about 8:45.[9]

The same newspaper provided the following description in its release one week later:

Those who were to one side and in position to see the storm say it was like a huge smoke hanging tail down from the clouds, wiggling along as if seeking to touch and fasten onto everything in its tract. [6]

Many accounts of the sights and sounds of the storm are consistent, in that they include a loud roar that was heard a half-hour or more before the tornado struck, ominous clouds approaching from the southwest, a frightful electrical storm, and a period of calm just before the tornado arrived. Most written accounts indicate that the storm struck without warning. In many versions, there is no mention of a funnel cloud, and in some versions there are specific words to the effect that no funnel cloud was visible from Snyder. It is likely that the funnel cloud either was rendered invisible by darkness, or it was obscured by rain and hail ahead of it. Or perhaps it was so large that it was not recognized for what it really was.

A release by the Associated Press included the following:

The denizens of the place had very little warning of the approaching storm. A strong wind had been blowing all day followed in the early evening by a torrential rain and frightful electrical storm. Between eight and nine o’clock, the storm came howling from the southwest. At the first sound of the approaching tornado many ran to places of safety, while others, not realizing the danger, failed to secure shelter and were consigned to the mercies of the storm. [12]

The same article also included the following account from an interview with R. Pritchard, described as “one of the leading men in the stricken town”:

“The cyclone struck Snyder about nine o’clock. It may have been a few minutes later. It came without warning. To the best of my recollection there was a dead calm just prior to the blast of wind. When the ‘twister’ struck Snyder it seemed that the air was filled with flying timbers in an instant. Buildings that would be considered substantial structures anywhere were torn asunder as if made of paper.

“It was all over in fifteen minutes, but it seemed to last for an age. God alone knows what we have passed through since that time.” [12]

An article from Granite, OK (30 miles northwest of Snyder) includes the following:

The cloud that carried the tempest came up rather suddenly from the southwest yesterday evening. It was not an unusually bad looking cloud and it is probable that there was no funnel shape formation, as had there been, it would have been visible from here.” [11]

From Hobart (25 miles north of Snyder):

For some time a dark cloud, accompanied by a constant blaze of lightning, had been gathering in the southwest, but its approach gave little or no concern to the majority of the people of [Snyder]. But all of a sudden and without a moment’s warning, the dreaded funnel shaped cloud was formed and… dropped to the earth like a gigantic balloon, and the work of death and destruction began. [13]

The Daily Oklahoman (Oklahoma City, 90 miles northeast of Snyder) contained the following description of the storm:

The storm formed south of Olustee, near the Texas line, and took a northeasterly course through a well-settled section. At 8 o’clock it was observed by the people of Snyder but the usual funnel-shaped formation was lacking, and though the deep roar was plainly heard for some time before the storm broke, many were of the opinion that it was a hail storm. Within a few minutes the sky became suddenly dark and a terrific downpour of rain began, lasting for several minutes, when it stopped almost as suddenly as it had commenced. A few moments of ominous calm followed, and then the tornado struck, tearing buildings to pieces as though they were made of paper.[14]

Articles in the May and August 1905 issues of Monthly Weather Review (U. S. Weather Bureau) provide these descriptions of the storm from shortly after its inception near the Red River:

The first appearance of the tornado was that of a black cloud from which was pendant a long funnel, almost perpendicular, and widening out from its base. To the people watching it from the front this funnel…seemed to zig-zag back and forth, apparently threatening all points of the compass to the eastward and leaving no point for escape. To the people watching it from the towns to the northward it appeared to be approaching, and not until it passed to the eastward were their fears relieved. At Olustee, O. T., the funnel shape was not noticeable until the tornado had passed to the eastward, it appearing as a broad band of water stretching from the earth to the cloud, and was at first thought to be a waterspout. To the people in its front the base of the funnel seemed enveloped in a cloud of steam, pouring continuously in and upward. Lightning was not specially noticeable until its junction with the second tornado at the mouth of Otter Creek, then it was continuous and blinding.

During its passage through Greer County the rain and hail occurred after the tornado passed, but it was both preceded and followed by rain in its passage through Kiowa County.

The noise of the tornado was heard over a radius of 12 miles from its path, and consisted of a grinding, crashing roar that was indescribable [sic].[5]

Most eyewitness accounts from Snyder suggest that the tornado struck without warning. However, a different picture emerges from the following article from Frederick (15 miles south of Snyder):

Ominous looking clouds were observed by our citizens Wednesday evening, gathering west of Snyder. It seemed to pass over that point about dark, when it was accompanied by intermittent flashes of lightning. It seemed the outside world knew more of the approach of the storm than did the unfortunate people right in the path of the cyclone. Both from the north and south, Snyder was warned by telephone.

Farmers along the rural route heard the Snyder telephone give a scream, as the storm struck the building. This was the last heard from there. [15]

From Bessie, 45 miles north of Snyder:

The tornado approached in a manner that deceived most persons. First came rain, then hail, then a lull, a succession not regarded as indicative of a tornado. [Note: This sequence of events is known today to be quite typical of many tornadic thunderstorms.] The lull was followed almost instantly by an appalling roar. Snyder is almost entirely surrounded by isolated peaks of the Wichita.mountains. The tornado came through a gap in the mountains southwest of town. A man living seven miles west of Snyder, who watched the tornado pass his farm, says it glowed like a vast furnace while in the air, but darkened whenever it struck the earth. The striking of the tornado was followed by a detonation louder than the thunder of many guns. [16]

Snyder, a town of roughly 1000 inhabitants in 1905,[17] was struck first at around 8:45 PM local time just north of the southwest corner of town. The tornado then tracked northeast, virtually wiping out every building on the west and north sides of town. It was reported that only a few buildings were undamaged (numbers range from two or three, to as many as 20), those being mainly on the south or southeast sides of town.

Accounts of the moments immediately following the tornado present a vision so horrifying that is hard to comprehend. “The largest number of killed and injured was at Snyder. Here the working of the storm was appalling and the damage and devastation were beyond description.”[12] It was dark, and the destruction was so complete that the surroundings were virtually unrecognizable. Survivors who climbed out of the wreckage were dazed and totally disoriented. A heavy rain followed the tornado, making it nearly impossible to care for the injured. A newspaper headline from nearby Mangum called it, “The Most Appalling Visitation of Nature Ever Visited Upon a Rural Population in the History of the United States,” [18] and an Ex-Union soldier said he had never seen anything like it since the battle of Shiloh. [15]

From the Associated Press:

In a few moments all was over and the shrieks and cries of the poor unfortunates filled the air. In the darkness of night could be heard the calling of lost ones – parents seeking their children, husbands their wives, little voices calling for papa and mamma. The tones which went out upon the night air were heartrending and pitiful in the extreme. Many of those sought were cold in death, and their voices hushed. The shrieks and groans of the dead and dying [sic], mingled with notes of the ones who had escaped seeking their loved ones, were painful to listen to. [12]

Livestock and farm animals lay dead everywhere. Chickens were found dead, “with their feathers blown out as cleanly as if they had been picked.” The carcasses of some horses were carried over a mile. [15]

The Altus Weekly News was published a day late that week, “for the purpose of ascertaining the extent of the cyclone.” The front-page article concluded with, “Never before have we, and never again do we, wish to witness such utter destruction of life and property. It was simply awful to realize that such things could be.” [19] The Frederick Enterprise, published the same day, concluded with, “The pathetic pictures which were seen on all hands will never be effaced from those who beheld them, and the most sceptical [sic] could not but admit the power of the Omnipotent one, and it is hoped that the people will learn lessons of right living that they will never forget.” [15]

Snyder was in desperate need of help from neighboring communities from the first moments after the storm, but the tornado took out every phone and telegraph line into and out of the town. In those days, there were only three ways to communicate with the outside world: Telephone, telegraph, and tell people face to face. With the first two options eliminated, messengers were sent on foot to the nearest town of Mountain Park, three miles north, to send news and ask for assistance. From there the message was sent by phone to nearby Hobart (lines were still up in Mountain Park), and from Hobart, word went out to all neighboring towns and to the rest of the world.[20] Many nearby towns immediately organized relief trains and dispatched them immediately to the stricken town. Trains arrived from Hobart, Frederick, Chickasha, Vernon, Davidson, Eldorado, Quanah, Oklahoma City, Mangum, Altus, Lawton, and several other towns in the area. These trains, loaded with supplies, doctors, nurses, and recovery volunteers, arrived every few minutes from late that night through the following day.

The following lengthy account of the hours and days following the tornado appeared in the May 12, 1905 edition of the Snyder Signal Star. It was printed in Frederick, most likely on the following Monday or Tuesday (May 15 or 16), as the newspaper’s printing press was “under a pile of debris and covered with slime and brick from a chimney, then three of the injured ones have been cared in the editor’s home which is in the rear of the building, and their condition precluded any effort to run the press.”[6] What follows was written by one of the first responders to the disaster, and is considered as comprehensive and accurate as any available description of the storm aftermath:

When the spared people crept out of caves [storm cellars] or came from houses which had not been claimed by the wrath of the wind, they stood for a moment stunned and dazed. Frantic appeals for help and pitiful moans of the dying fell upon dulled ears for an instant, and then the town awoke to the necessity of action and the work began.

Soon the dead and wounded were both being carried into available rooms, but later the rescue work was devoted alone to the living, and this work continued throughout the night. “Oh for daylight” was the plaint of many burdened hearts as they sought for loved ones and the air was filled with cries welling up from hearts filled with anguish when the lifeless forms of dear ones were found. The Pritchard building and the Peckham building were in a few minutes filled with the injured and dead. Both living and dead were horrible in appearance. Clothing had been torn into rags or completely from the forms. Through the slimy black mud which covered every face it was almost impossible to recognize features. This made the work of identification very difficult and most of the identifications were arrived at through recognition of some article found on their persons. Soon the search for loved ones was transferred to the rooms temporarily turned into morgues and hospitals. Oh, the agony of it all. The uninjured searching among the dead and injured for some lost one – the pitiful inquiries made by injured ones for those that were with them when the storm struck, and their appeals for further search to be made. Men who had not shed a tear for years cried like children – there was no effort to conceal the tears which forced themselves into the eyes of those whose desire to assist forced them to look upon the awful sights to be seen on every side. Pen can never describe the horror of it all, so that those who have not passed through similar trials can arrive at one tenth part of the awfulness of the suffering of the injured and appearance of the dead.

Soon after the storm had lulled, the block in which the Chinese laundry was located, and which had been heaped in a pile by the wind, was found to be burning. A strong north wind was carrying fire brands to the business houses which had been left standing, and a heroic fight was made to prevent a general conflagration. Luckily the gutters were so full of water that water enough was secured to put the fire out. It had to be fought by inches, the crackling flames roiling and pitching as if jealous of the havoc the wind had made in so short a time. A fire also broke out in the partially destroyed Worsham building, but quick work overcame it and the Woodard, Tennison & Hoffmaster and Wey buildings were saved from the general destruction.

DAYLIGHT CAME.

And permitted a view of the destruction wrought. Where hundreds of dwellings had stood when the sun went down, not an upright stick remained and but an open prairie greeted the eye. As was said before, the ruin was complete from where the storm struck the town a little north of the school house and on the west line of town through to the north east part of the town. It mowed a path from five to seven blocks wide. Nothing stood which was in the path of the storm, and many buildings which were not in the direct path were wrecked. Not a building was standing which does not show some of the storm’s work. Not a person who was in the direct path of the storm escaped serious injury or death, save those who took refuge in storm caves or cellars. Not a horse, cow, or pig escaped – all fell victims to the greedy storm.

The work of rescue was resumed as soon as day break, the injured being cared for first and the dead then gathered up and hauled to the morgue by wagon loads. It was a grewsome [sic] sight, and yet men and women who would ordinarily shriek at the sight of blood and suffering, with set features stoically went about doing the best they could for those who needed help.

A hospital was established in the large room at the west side of the Hilton building, and all would be conveyed there who had not through the night been taken to some private residence.

The Tennison & Hoffmaster building was taken as a morgue and very soon the floor of the 50x80 room was crowded with the remains of men, women and children. The sight was appalling and only the awfulness of the occasion gave men strength to properly care for the bodies. Every stitch of clothing which had not been torn off and every part of the person exposed were simply solidly cemented with a slimy black mud. The clothing was removed, the poor mangled remains as nearly cleaned as they could be and each body wrapped in muslin to await final burial. The shelves and the counters were filled with these, reminding one of the stories of old Catacombs where tier above tier of bodies are to be seen.

Volunteers were called for to dig graves and make coffins, and though many responded, not much headway was made the first day toward burying the dead.

RELIEF PARTIES.

Soon after the storm, S. B. Odell walked to Mountain Park and gave the alarm – but he talked so daffy as everyone who went through the storm did – that people wouldn’t believe him. He had been followed by Edgar L. Bealle and Fred C. Sweitzer, and when they too told the story of the awful calamity the town was aroused and every man able to get here came over and assisted our people in work of rescue and such other work as was needed. The writer, with others, was fighting the fire when a party of men came up and said, “We are here to help and others are coming.” It was the first of the kindly feeling which soon came to us from all surrounding towns, and their promptness will always be treasured in the memory of those who met that first party.

When Sweitzer and Bealle succeeded in arousing the Mountain Park operator to the needs of the hour, the news of the calamity out-speeded the storm and all the towns within reach began making up special trains.

The train from Hobart, which arrived between 3 and 4 o’clock a.m. bringing seventy-five men and women, several doctors among them, was the first to reach here and no party of people received a more heartfelt welcome than they did. It was not evidenced by a noisy demonstration but by silent pressure of the hand and tearful expressions of gratitude. Following the Hobart train, special trains arrived every few minutes, and our people soon realized that the disaster had made “all people kin” – that everybody within reach of us was our friend. Soon cars loaded with needed supplies for hospital and homeless people began to arrive.

THE RELIEF COMMITTEE.

By 11 o’clock Thursday morning a mass meeting had been called together for the purpose of organization. A general Relief Committee consisting of E. P. Dowden, B. C. Burnett, G. J. Helena, Fred C. Sweitzer and W. M. Allison was elected and E. P. Dowden made chairman, G. J. Helena treasurer and B. C. Burnett secretary. On the ground a subscription for relief was started and considerable money subscribed by gentlemen who were present at the meeting. Thus was the relief work put under organization. The world was notified that supplies of all kinds were needed and request made that all remittance and shipments be addresses to G. J. Helena, Treasurer.

A quartermaster department, and under it a commissary department, were established and everything put in shape to carefully take care of everything that came in and the needs of those who are homeless. Everything was systematized and at this writing are running smoothly and in a satisfactory manner. The general committee have divided the work between them so that each member is in direct charge of a certain department and the needed work.

E. P. Dowden has charge of the supplies; G. J. Helena the finance; Fred C. Sweitzer the rebuilding; B. C. Burnett cleaning streets and town of debris and dead animals; and W. M. Allison of the hospital.

Hundreds of ladies have come in and offered their services as nurses to the sick. Many have served as long as they could and then given away to others who were anxious and willing to assist. Snyder owes these noble women a debt of gratitude which can never be amply repaid.

On Friday two heavy rain storms came, and as the roof had been partly torn from the building in which the hospital had been opened, it looked much for a time as if the sufferers would all be drowned. But speedy work by many willing hands saved them and they were removed to another room in same building. This room was too small and Dr. Borders, who had been installed as head surgeon, insisted on a better room. As none could be found which had escaped injury, a roof was put back over the first room by Pete Coen and a gang of volunteers. A partition was run, an operating room built and drug room arranged and the patients all returned to the room Sunday morning. They are now as comfortably situated as they can be made under all the circumstances. Doctors from other towns and scores of ladies and gentlemen have, from time to time, taken their turns as watches and nurses and the wounded are being well cared for.

CLEANING UP.

Sunday 100 men came down from Hobart (and) organized into ten companies with a captain over each. These man will ever hold the admiration of Snyder. Monday a party from Eldorado and some from other points returned, and good work toward clearing up debris and burning animal carcasses was accomplished.

The territorial Engineering Corps, under command of Captain King, have been valuable assistance in maintain order and clearing up. They too will ever be dear to Snyder.

The town will be rebuilt. The work of restoring buildings has already begun, and though it will take the town some time to fully recover its old appearance and activity, it will certainly do so. [9]

One of the more interesting tales that arose from the 1905 disaster is actually a legend that began well before the tornado. Snyder was founded in 1902, within a year after the Kiowa-Comanche Reservation was opened to non-Indian settlers, and only three years before the tornado. It is said that several Kiowa Indians warned the settlers to move their town to a nearby secluded valley. The Kiowa legend maintained that a tornado had destroyed an Indian village on the exact site of Snyder several years earlier, and that the gods eventually would destroy anyone who tried to live there. Most of the settlers merely considered the claim to be a scare tactic.[21]

The Indian legend may have roots in a story related by local citizens, which found its way into print in the days following the 1905 tornado. It seems there was an old resident Indian who claimed that a windstorm worse than the 1905 tornado passed over the same spot twenty years earlier. The place also was visited by tornadoes twelve, seven, and three years earlier, all but one of which passed over the same identical ground, the other passing on the other side of the adjoining mountain range. [22]

The Kiowa legend apparently gained more advocates after the 1905 tornado, or at least there were people beginning to believe that tornadoes, for whatever reason, simply “had it in” for Snyder. This in turn led to the following cynical commentary, which appeared in the Kiowa County Democrat on the one-year anniversary of the 1905 storm:

Some people really believe that the erratic and justly phenomena known as the cyclone has certain beaten paths which it follows in preference to any other. They imagine that the twister is positively unhappy unless it can get on to one of these trails. This idea results in an injustice to certain vicinities – Snyder, for instance. Among the first thing we heard after the cyclone there, was the report that a certain old Indian (whose age exceeded his veracity) claimed that Snyder is in a regular nest of cyclones; that cyclones made that their headquarters and always managed to visit that place regardless of expense. All this was never thought nor heard of until after a twister struck that town. Some Indian may have been the father of that fiction, or he may not. Suppose he was: the “Noble red Man” is hardly so reliable and truthful as Mulhatton or Munchauson. Whatever he says about the past or present of this country, you will generally find it just the other way.” [23]

Be that as it may, a check of weather records reveals that no less than 21 tornadoes have passed within a few miles of Snyder since the May 10, 1905 event. Luckily, few of them have caused serious injuries or major damage within the town itself. Notable among them were the tornadoes of April 18, 1917 (25 buildings demolished in town; fifteen injuries, and one fatality 8 miles west of Snyder, but no deaths in town), June 16, 1928 (at least seven people killed between Blair and Headrick; every building in Headrick was damaged or destroyed before it passed just to the southwest of Snyder), June 5, 1936 (moved north, killing one person several miles south of Snyder before passing a mile west of town), May 1, 1954 (began east of Crowell, Texas and moved northeast nearly 70 miles, ending just south of Snyder; one mile wide at times), and February 22, 1975 (moved from just west of Snyder to Mountain Park; a 2-year old boy was killed in a trailer).

As with any such catastrophe, many individual stories emerged from the Snyder tornado disaster. They serve to drive home the true range of human emotions that affected the sufferers. Following are but a few tales that have survived over the years:

The destruction of the Fessenden family, consisting of six members, was complete. Miss Nina Fessenden, a daughter, was to have been married the night of the cyclone to Clarence Donovan, a railway engineer. The wedding was postponed, because of some trivial matter, until the following morning. Both of them were killed in the tornado. [12]

The family of Fred Crump, 17, were in the cellar of their home. Family members said that Fred had just started down the steps, when a piece of timber struck and killed him.

Cal Williamson, said to be one of the leading citizens of the town, hurriedly picked up a woman whom he thought was his young wife. As the tornado struck, he carried her to safety. When the storm abated, it was discovered that the woman he saved was not his wife. He later found his wife among the victims.

Charles Landon Hibbard, superintendent of Snyder Schools, died on his way to the storm cellar, along with his wife, mother, father, and two of his four children. His parents, being elderly, could not move quickly enough, nor could the smaller children. Professor Hibbard slowed his steps to match those of his family members, while his 12-year old son Lloyd was sent ahead to open the cellar door. Unfortunately, all of the family except Lloyd, and his brother Edward, died before reaching the cellar.

Three children were killed in the Crook family, all under the age of three years. The youngest, three months old, was blown from its mother’s arms, thrown against a brick wall, and killed. [24]

An upright piano was found in a field eight miles from town, sitting in a field in the same position as it was when picked up by the cyclone. Pictures and papers from the wrecked homes in Snyder were found in Caddo County on the other side of Saddle Mountain, 55 to 60 miles away. [6]There were several reports that there was more debris littering the streets of Mountain View, 30 miles to the north northeast, than there was left in Snyder.

Immediately after the storm, some news reports suggested the death toll in Snyder would reach as high as 400. These reports turned out to be either gross overestimates or outright exaggerations. The reported number of victims was soon revised downward, and eventually the numbers converged toward a range somewhere between 90 and 130.

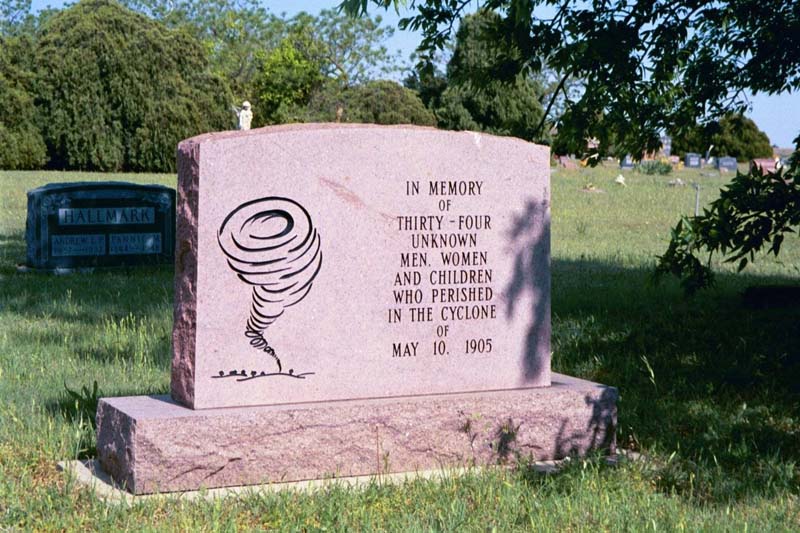

The facts, as well as can be determined, are as follows: 1] Published lists contain partial or complete names of 86 known victims from Snyder and surrounding areas in Kiowa County. 2] Other lists and accounts provide names of at least nine others that died in Greer County as a result of the first of the two tornadoes. 3] Many of the known victims were laid to rest in Fairlawn Cemetery, outside of Snyder, but some were laid to rest elsewhere in Oklahoma and Kansas. 4] An unknown number of unidentified victims were buried in a mass grave at Fairlawn Cemetery. 5] A stone marker, placed in Fairlawn Cemetery in the 1990s near the alleged site of the mass grave, reads, “in memory of the thirty-four unknown men, women and children who perished in the cyclone of May 10, 1905.” 6] According to the Oklahoma Historical Society, two of Oklahoma’s most distinguished historians placed the count at “about 120 dead.” [25] 7] Fires in the wake of the tornado burned parts of the wreckage in the business area of town. “Whether or not any of the bodies of dead or wounded were cremated is not known, but the general belief is that some were in the fire-swept ruins.” [9] 8] Local residents in Snyder said that a passenger train stopped in town that evening, and dropped off an unknown number of passengers before pulling out shortly before the tornado struck. Many of these passengers may have been from out of town, and thus would have been relative unknowns to most of the citizens of Snyder. Passengers that were still at or near the railroad depot when the tornado struck most likely were either killed or injured.

The exact number of people killed by the Snyder tornado will never be known with absolute certainty. We can only arrive at a reasonable estimate, based on the information available. Beginning with facts 1] and 2], above, we know of at least 95 victims. Fact 3] means we can not refine the count based in the graves in Fairlawn Cemetery. Fact 5] likely derives directly from fact 6] and fact 1], and assumes a total of 120, of which 86 are known. It is considered unlikely that any bodies were completely incinerated by post-tornado fires (Fact 7]), but this possibility can not be ruled out completely. Fact 8] would most likely affect only the relative number of unknown or unidentified victims, and not the total.

If we accept the historical estimate of 120 deaths from the entire event, and account for the nine known victims in Greer County, we would arrive at a reasonably reliable estimate of 111 deaths from the Snyder tornado. This is roughly ten to 12 percent of the entire population of the town at the time, one of the highest such ratios of any tornado in history. The high death toll is attributed partly to the fact that the storm struck after regular business hours, when most of the inhabitants were at home. Although the business section received major damage, the worst of it was in the residential sections on the west and north sides of town.

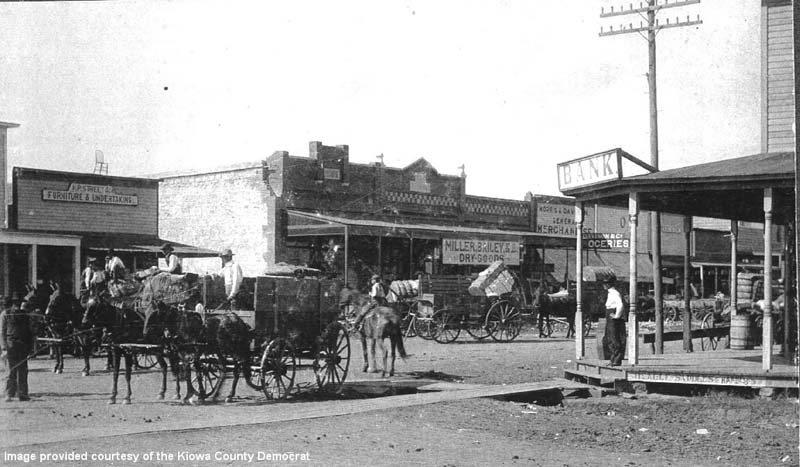

More than one hundred years later, Snyder is by all accounts a rather typical and peaceful Oklahoma town, and shows no scars from the events of a century ago. Thanks to the tornado, and to other calamities,[26] nearly the entire town has been rebuilt and all of the structures have been erected after 1905. Only two buildings still stand in town that were not taken by the tornado or by other events over the last hundred years. One of the buildings, which housed the Snyder Hotel on the top floor and a dry goods store on the first floor, can be seen in a photo[27] taken within days after the 1905 tornado had damaged it, and also in a photo taken in April 2005. The population, according to the 2000 census, is 1,509. The nickname for the local school is “the Cyclones.”

|

|

| Photo #1: View looking to the southeast at damage which occurred in the business section of Snyder, Oklahoma during the May 10, 1905 Tornado. Photo credit: Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Library. Used by permission via Don Burgess, NSSL and the WHC-OU Library. | Photo #2: View of people searching through the rubble of destroyed buildings in Snyder, Oklahoma after the May 10, 1905 Tornado. Photo credit: Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Library. Used by permission via Don Burgess, NSSL and the WHC-OU Library. |

|

|

| Photo #3: View of damaged building which housed the Snyder Hotel and a dry goods store in Snyder, Oklahoma. Photo credit: Kiowa County Democrat, Snyder, OK. | Photo #4: View of building which formerly housed the Snyder Hotel and a dry goods store in Snyder, Oklahoma. Photo was taken in April 2005. Photo credit: NWS Norman, OK. |

|

|

| Photo #5: View of Main Street in Snyder, Oklahoma in the early 1900s prior to the May 10, 1905 Snyder Tornado. Photo credit: Kiowa County Democrat, Snyder, OK. | Photo #6: View of memorial tombstone dedicated to 34 unknown victims of the 10 May 1905 Snyder Tornado. The memorial was placed at the Fairlawn Cemetery near Snyder in the 1990s. Photo credit: NWS Norman, OK. |

|

|

| Photo #7: View of the mass grave for 34 unknown Snyder tornado victims(marked by a concrete "square" and to the right of the center tree) and memorial marker at the Fairlawn Cemetery. Photo credit: NWS Norman, OK. | Photo #8: Another view of the mass grave for 34 unknown Snyder tornado victims at the Fairlawn Cemetery. Photo credit: NWS Norman, OK. |

|

|

| Map #1: U.S. Weather Bureau Surface Analysis at 7:00 am CST (1300 UTC) on May 9, 1905. Map Credit: NOAA Central Library Data Imaging Project. Daily Weather Maps, 9 May 1905. | Map #2: U.S. Weather Bureau Surface Analysis at 7:00 am CST (1300 UTC) on May 10, 1905. Map Credit: NOAA Central Library Data Imaging Project. Daily Weather Maps, 10 May 1905. |

|

|

| Map #3: U.S. Weather Bureau Surface Analysis at 7:00 am CST (1300 UTC) on May 11, 1905. Map Credit: NOAA Central Library Data Imaging Project. Daily Weather Maps, 11 May 1905. |

|

|

| Map #4: U.S. Weather Bureau Surface Analysis at 7:00 am CST (1300 UTC) on May 9, 1905. Map credit: United States Government. Army Air Forces and Weather Bureau. Historical Weather Maps: Daily Synoptic Series, Northern Hemisphere Sea Level, May 1905. | Map #5: U.S. Weather Bureau Surface Analysis at 7:00 am CST (1300 UTC) on May 10, 1905. Map credit: United States Government. Army Air Forces and Weather Bureau. Historical Weather Maps: Daily Synoptic Series, Northern Hemisphere Sea Level, May 1905. |

|

|

| Map #6: U.S. Weather Bureau Surface Analysis at 7:00 am CST (1300 UTC) on May 11, 1905. Map credit: United States Government. Army Air Forces and Weather Bureau. Historical Weather Maps: Daily Synoptic Series, Northern Hemisphere Sea Level, May 1905. |

Tornado F-scale ratings prior to 1950 are referenced from Significant Tornadoes, 1680-1991.by T. P. Grazulis.

| OK# | Date | Time (CST) | Length (miles) | Width (yards) | F-Scale | Deaths | Injuries | Counties | Path |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 05/10/1905 | 2045 | 22# | 880 | F5 | 97* | 58* | Jackson/ Kiowa | 3 SSW Humphreys - Snyder - 3 NE Snyder |

|

This tornado developed about 2-3 miles southeast of the Frances school house (~3 miles south-southwest of Humphreys) in old Greer County (now Jackson County). Homes were swept away about 14 miles southeast of Altus. From its inception, this tornado moved east-northeast crossing the North Fork of the Red River near the mouth of Otter Creek. The tornado followed very close to Otter Creek curving to the northeast through what is now northern Tillman County (but was still part of Kiowa County at the time). Three people were killed about 6 miles southwest of Snyder. As the tornado continued to the northeast it struck the city of Snyder around 8:45 pm CST. The tornado moved into the Snyder beginning in the southwest corner of the town, and destroyed or damaged homes and other buildings west of Main Street and and from 6th Street northward through the city. No buildings north of the railroad were left standing. After moving through Snyder, the tornado continued northeastward, destroying a couple of small residences within two miles of the town site, then lifted about three miles northeast of Snyder. * Current "official" numbers. # Path length is approximated and is based on research done by NWS Norman staff. |

|||||||||

| 2 | 04/18/1917 | 1855 | 30 | 50 | F3 | 1 | 15 | Jackson/ Tillman/ Kiowa | Near Altus to between Snyder and Manitou |

|

A tornado destroyed a school 2 miles southwest of Snyder and then swept northeastward through the residence section on the southeast side of the city of Snyder. The path width was about 150 yards wide and about 75 buildings were either damaged or destroyed. No one was killed, but 15 persons were injured. Many horses and cattle were killed, and property losses totaled about $100,000. |

|||||||||

| 3 | 06/16/1928 | 1815 | 30 | 880 | F4 | 7 | 21 | Jackson/ Kiowa | Near Blair - near Headrick |

|

The tornado moved southeast from about 5 miles northwest of Balir and passed directly through the town. Many homes were swept away on the southwest side of Blair, and the tornado killed three persons in the town. The tornado moved southeast and killed four people near Headrick before dissipating. Over 1,000 cattle were killed by the tornado and downburst winds produced by the parent supercell thunderstorm. |

|||||||||

| 4 | 06/05/1936 | 1730 | 6 | 75 | F3 | 1 | 1 | Kiowa | SW of Snyder |

|

This tornado moved to the north and passed 4 miles west of Snyder. One person was killed and one person was injured. Several buildings were demolished, and 20 head of cattle and several horses were killed. |

|||||||||

| 5 | 04/30/1942 | 0530 | 0.5 | 50 | F? | 0 | 0 | Kiowa | Snyder |

|

A small tornado touched down in Snyder, producing a half-mile damage path to property in the town. |

|||||||||

| 6 | 05/23/1952 | 0430 | 17 | 100 | F1 | 0 | 0 | Kiowa | East of Snyder |

|

This tornado formed near Snyder and moved northeast, destroying two barns east of Snyder. |

|||||||||

| 7 | 05/01/1954 | 1416 | 69 | 440 | F4 | 0 | 2 (0) | Foard TX/ Wilbarger TX/ Tillman/ Kiowa | Crowell and Elliot areas TX - E of Tipton - near Snyder |

|

This tornado originated in western north Texas near Crowell and passed to the east of Vernon befor entering southern Tillman County. It moved from east of Tipton into Kiowa County south of Snyder. Twenty farms, one school and a cotton gin were damaged on the Oklahoma side. |

|||||||||

| 8 | 06/14/1955 | 2030 | 18 | 500 | F2 | 0 | 0 | Kiowa | Snyder |

|

A tornado traveled 18 miles through Kiowa County, and destroyed 4 barns in the Snyder area. |

|||||||||

| 9 | 05/24/1962 | 2313 | N/A | N/A | F0 | 0 | 0 | Kiowa | 4 SW Snyder |

|

A small tornado touched down briefly 4 miles southwest of Snyder and produced minor tree damage at a farm. |

|||||||||

| 10 | 02/22/1975 | 0100 | 5 | 75 | F2 | 1 | 2 | Kiowa | W of Snyder - Mountain Park |

|

A tornado touched down just west of Snyder and moved north-northeast to Mountain Park. Power lines poles were knocked between Snyder and Mountain Park. A two-year-old boy was killed when the mobile home he was in was destroyed. |

|||||||||

| 11 | 06/23/1976 | 2355 | 0.3 | 30 | F1 | 0 | 0 | Kiowa | 3 W Snyder |

|

A small tornado toppled a power line 3 miles west of Snyder. |

|||||||||

| 12 | 05/20/1977 | 1800 | 4 | 100 | F2 | 0 | 0 | Kiowa | Near Snyder |

|

A tornado initiated near Snyder and damaged two houses, a pickup truck, and some outbuildings. |

|||||||||

| 13 | 05/14/1986 | 1505 | 1.1 | 75 | F1 | 0 | 0 | Tillman/ Kiowa | 5 SW - 3 SW Snyder |

|

This tornado was the third of four tornadoes produced by a parent supercell thunderstorm in southwestern Oklahoma. The tornado touched down 5 miles southwest of Snyder and moved to the east-northeast before dissipating 3 miles southwest of Snyder. The tornado damage an irrigation pipe, power lines and poles, a barn, and some trees. All four tornadoes were observed and documented by numerous storm chasers, and by researchers from the National Severe Storms Laboratory. |

|||||||||

| 14 | 05/14/1986 | 1509 | 3 | 500 | F2 | 0 | 0 | Kiowa | 2 S - 2 SE Snyder |

|

This tornado was the last of four tornadoes produced by a supercell in southwestern Oklahoma. The tornado touched down 2 miles south of Snyder and moved east, dissipating 2 miles southeast of Snyder. The tornado destroyed several barns and a travel trailer. It also damaged a house, power lines and poles, and trees. |

|||||||||

| 15 | 07/17/1987 | 1530 | 0.1 | 20 | F0 | 0 | 0 | Kiowa | 3 S Snyder |

|

A small tornado touched down briefly 3 miles south of Snyder, and did not produce any damage. |

|||||||||

| 16 | 10/29/1989 | 1646 | 0.1 | 30 | F0 | 0 | 0 | Kiowa | 4 W Snyder |

|

A small tornado touched down 4 miles west of Snyder, and briefly moved east-northeast over open country. |

|||||||||

| 17 | 06/05/2005 | 1836-1839 | 1 | 50 | F1 | 0 | 0 | Kiowa | 5 W Mountain Park - 5 WNW Snyder |

|

This tornado, the first to occur near Snyder in 15+ years, was observed by numerous storm spotters, storm chasers and media personnel. The tornado caused major roof damage to one home. Another home received light roof damage. A barn was also destroyed. Trees and limbs were also reported down. One home was located 5 miles west and 1.2 miles south of Mountain Park. The second home was located 5 miles west and 1.5 miles south of Mountain Park.The destroyed barn was located 5 miles west and 1.75 miles south of Mountain Park. |

|||||||||

| 18 | 11/07/2011 | 1515 | 6 | 400 | EF0 | 0 | 0 | Tillman/ Kiowa | 2.5 WNW Manitou - 4 S Snyder |

|

This large tornado developed west-northwest of Manitou, OK and moved north-northeast through rural areas into Kiowa County just east of U.S. Highway 183. The tornado then quickly dissipated about 4 miles south of Snyder, OK. No damage was reported in either county from this tornado. |

|||||||||

| 19 | 11/07/2011 | 1538 | 0.5 | 100 | EF0 | 0 | 0 | Kiowa | 2.5 E Snyder |

|

This brief tornado occurred 2.5 miles east of Snyder and north of U.S. Highway 62. No known damage occurred with this tornado. |

|||||||||

| 20 | 05/09/2013 | 1600 | 0.1 | 10 | EF0 | 0 | 0 | Kiowa | Snyder |

|

A brief, weak landspout tornado was observed in Snyder. This tornado caused minor damage to a carport. |

|||||||||

| 21 | 05/16/2015 | 1626 | 40 | 1600 | EF3 | 0 | 0 | Hardeman TX/ Wilbarger TX/ Jackson/ Wilbarger TX/ Jackson/ Tillman/ Kiowa | 8 N Chillicothe TX - 3 E Snyder |

|

This tornado touched down 8 miles north of Chillicothe in extreme northeastern Hardeman County in western north Texas and moved to the northeast. It moved into Wilbarger County and eventually into Oklahoma with a total path length of 40 miles.The tornado that began in northeast Hardeman County moved through the far northwest corner of Wilbarger County before crossing the Red River into Jackson County, Oklahoma. No damage was known to have occurred in the rural areas of of both Hardeman and Wilbarger Counties. The tornado moved from Jackson County back into Wilbarger County for a brief time before crossing back into Jackson County and moving across the southeast section of the Jackson County. Damage to trees, metal buildings and outbuildings were observed along US Highway 283 to the southeast of Elmer. Damage to homes and trees continued to be observed as the tornado moved east-northeast. The most significant damage was observed 3 to 4 miles east of Elmer. The tornadic motion seen on videos and the radar presentation indicate that this likely was a violent tornado through southeast Jackson County, although only EF3 damage was observed as the tornado moved through this relatively sparsely populated area. The Frederick, OK (KFDR) radar measured 115 knot gate-to-gate rotational velocity when the tornado was east of Elmer. The tornado continued east- northeast moving into Tillman County about 4 miles west of Tipton. The tornado moved out of Jackson County and continued northeast passing into Kiowa County north of Manitou. EF2 damage continued to be observed north of Tipton, but again the tornado moved through sparsely populated farmland across northwestern Tillman County . The tornado width decreased from 1300 yards to 700 yards by the time it moved into Kiowa County. The tornado moved into Kiowa County from Tillman County and finally ended it 's 40-mile path about 3 miles east of Snyder. Damage in Kiowa County was confined to broken power poles along US-183 south of Snyder and US-62 just southeast of Snyder as well as trees within the damage path. |

|||||||||

We wish to thank the Oklahoma Historical Society; the Western Heritage Museum, University of Oklahoma, Norman; Don Burgess; O. T. Brooks and Dee Richardson, Kiowa County Democrat, Snyder; and the staff of the Snyder City Hall; and A. J. Toma, co-owner/operator of the Toma Grocery in Snyder.

[1] Grazulis, T. P.: Significant Tornadoes, 1680-1991.

[2] Harrison Gazette, Gotebo OK, Friday, May 12, 1905.

[3] Time zones in the United States were established for the sake of the railroads in the 1880s, but were not necessarily adopted universally – even in 1905. Since Snyder was a railroad town, at the crossroads of two railroads, it can be safely assumed that Snyder and the surrounding areas adhered to the Central Time Zone. There was no such thing as Daylight Savings Time until 1918.

[4] Daily Oklahoman, Oklahoma City, Saturday, May 13 1905.

[5] Strong, C.M., “The Tornado of May 10, 1905 at Snyder, Okla.”, Monthly Weather Review, August 1905.

[6] Snyder Signal-Star , dated Friday, May 19, 1905.

[7] Altus Times, Thursday, May 11 1905. Lock had a reported population of 38, and consisted of a school, post office, one or two stores, and several homes.

[8] Altus Times, Friday, May 18, 1905.

[9] Snyder Signal-Star, dated Friday, May 12 1905.

[10] Guthrie Daily Leader, Thursday, May 11, 1905.

[11] The Granite Enterprise, Thursday, May 11, 1905.

[12] Associated Press news release; exact date unknown, but written in the days immediately flowing the tornado.

[13] The Hobart News Republican, Friday, May 12, 1905.

[14] Daily Oklahoman, Oklahoma City, Friday, May 12, 1905.

[15] Frederick Enterprise, Friday, May 12, 1905.

[16] The Washita Breeze, Bessie OK, Friday, May 12 1905.

[17] Newspaper accounts at the time varied considerably in their estimates of the population of Snyder. Figures ranged from as few as 600 to as many as 2,000. Today, the actual population in 1905 is estimated to have been somewhere between 800 and 1,200.

[18]The Mangum Star, May 11 1905.

[19] Altus Weekly News, Thursday, May 11 1905.

[20] According to local residents, stories of the Snyder disaster eventually appeared in the New York Times and London Times.

[21] Kelley, Leo: “Oklahoma: Home of the Real Twisters.” The Chronicles of Oklahoma, Oklahoma Historical Society, Winter 1996-1997, p. 428.

[22] The Washita Breeze, Bessie OK, Friday, May 12, 1905.

[23] Kiowa County Democrat, May 10 1906. Article appeared originally in the Manitou Field-Glass.

[24] This story, and the ones preceding, appeared with only slight variations in several of the local newspapers following the tornado.

[25] Kelley, Leo: “Oklahoma: Home of the Real Twisters.” The Chronicles of Oklahoma, Okla. Hist. Soc., Winter 1996-1997, p. 430. Five references are listed therein to support the death count of “about 120.”

[26] A fire in 1906 burned most of the business area east of E street (main street). Another fire in 1909 burned most of the business area on the west side of E street.

[27] Snyder Hotel damage photo and pre-tornado Snyder street photo provided courtesy of the Kiowa County Democrat, Snyder, Oklahoma.

[28]U. S. Department of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/NOAA Central Library Data Imaging Project. Daily Weather Maps, 9 May-11 May 1905.

[29]United States Government. Army Air Forces and Weather Bureau. Historical Weather Maps: Daily Synoptic Series, Northern Hemisphere Sea Level, May 1905.