|

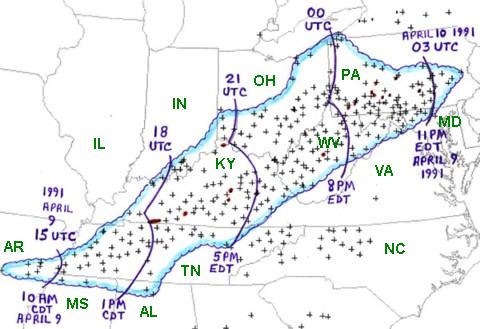

| Figure 1. Area affected by the April 9, 1991 derecho (outlined in blue). Curved purple lines represent approximate locations of gust front at three hourly intervals. "+" symbols indicate locations of wind damage or wind gusts above severe limits (measured or estimated at 58 mph or greater). Red dots and paths denote tornadoes. |

A squall line formed from a thunderstorm complex that originated in Arkansas around dawn. It moved toward the northeast at about 70 mph (60 knots) during the day on Tuesday April 9, 1991. This speed was faster than the ambient wind flow. The squall line reached the Huntington vicinity around 1630 EST with thunderstorms containing precipitation to 55,000 feet. The north/south squall line traversed the state from southwest to northeast during the evening. People caught outside had little time to seek shelter. Weather radar identified a "bow echo" on the line of thunderstorms as it moved from the Kanawha Valley toward Elkins.

The gust front along the leading edge of the squall line produced a sudden and dramatic increase in the wind and barometric pressure. The high winds lasted only 2 to 5 minutes at any one particular location. Several residents described the roaring sound that accompanied the arrival of the gust front as like the engines of jet aircraft. This gust front crossed the mountains and exited the eastern panhandle around 2045 EST. Temperatures dropped from the 80s to near 60 in 20 minutes as the storms streaked through many of the counties.

Based on damage surveys, instantaneous wind gusts of 100 to 110 mph were reached in a few favored areas. Channeling by valleys, hollows, or hilltop exposure toward the southwest probably aided the wind in reaching those speeds.

Anemometers measured the following gusts:

These straight line winds and downbursts caused two deaths, 86 injuries, and an estimated $16 million in damage in West Virginia. The first death occurred in northern Cabell County when a cinder block wall of a barn collapsed onto a 41-year-old male. The site was on a horse farm 1 mile northeast of Green Bottom. The other fatality, a 4.5-month-old boy, died when his grandparents' mobile home was blown over and rolled down a 20-foot embankment while breaking into pieces along East Point Drive in Charleston.

Most of the injuries were caused by flying debris. In many instances the debris was ripped off large flat roofs. One serious example took place at a track meet at Ripley High School of Jackson County. Sections of the band roof were torn off, along with large gravel rocks. The debris and rocks were hurled into the parking lot and through the windows of a nearby annex building. Ten people were injured. A few students were blown into a fence. Several people found shelter under the concrete grandstands.

Another major cause of injuries was when mobile homes were overturned or ripped apart. Four people were injured 1 mile northwest of Leachtown in Wood County in an area known as Bruckner Bend. A mobile home was destroyed as it was rolled by the wind at Fort Ashby in Mineral County, injuring one person. Two people were hurt near Rowlesburg in Preston County when their mobile home was blown off its base. Near Cyclone in Wyoming County, three mobile homes were destroyed, injuring one woman. Uprooted trees also caused injuries. An oak tree fell on a car along WV Route 15 in Braxton County, breaking the back of a male passenger. A 10 year-old boy was trying to get home on his bike, when a tree fell on him in his Buckhannon yard.

​Hail as large as golf balls accompanied the storms but did little damage. Upon final analysis, only one weak (F0) tornado was confirmed near Frametown in southern Braxton County. Its damage was limited mainly to trees.

Significant damage occurred 49 of the 55 West Virginia counties. The only major region that escaped the storm's fury was the southeastern counties around Bluefield and Lewisburg. The two top insurance companies in West Virginia reported a total of about 8,000 claims for property damage to businesses and homes. The Red Cross set up emergency centers in several locations. The most monetary property damage was reported from Kanawha, Lewis, Braxton, and Putnam Counties.

Typical damage accounts throughout the affected region included: sections of roofs or shingles blown off; insulation scattered about; windows shattered; tin roofs, awnings, porches, carports and rain spouts ripped away from the main dwelling; underpinning around mobile homes torn away; mobile homes flipped or rolled over; roofs ripped off mobile homes and crushing vehicles and crashing through roofs; commercial signs, street signs, and fences blown over or bent; barns, outbuildings, and sheds demolished; press boxes and scoreboards at athletic fields were damaged or destroyed. Hundreds of families had to seek temporary shelter elsewhere, due to damaged homes.

Here is a summary that highlights a few of the specific accounts of damage.

Secondary damage included water draining into damage dwellings from the showers behind the gust front. Thousands of trees were partially or totally blown over. Evergreen trees were especially vulnerable. Near Kingwood in Preston County, over 100 pine trees were fallen in a 3 to 6 acre plot. Deciduous trees were budding in the lower elevations, but not yet in full leaf. Rural counties, such as Calhoun, Ritchie, and Wirt, reported almost every main road blocked by fallen trees.

Electrical power to around 200,000 units from two utility companies were severed by falling trees and poles. Flickering lights and power surges preceded the gust front, foretelling many residents that something unusual was happening. It took until Sunday, April 14th, to restore power to all affected customers. Many stores and homes lost food items due to the lack of power to all affected customers. Many stores and homes lost food items due to the lack of refrigeration. Emergency communications within several counties were also down due to power outages. School systems were shut down in seven counties the following day, due to damaged facilities or lack of electricity.

Thunderstorm wind damage on this large scale is extremely rare in West Virginia. The roaring sound and the force of the gust front led many to believe they had experienced a tornado. One Gilmer County resident summed up the feeling of many West Virginians when stating, "I don't know what it was, but whatever it was, I don't want to see it again."