The 1930s were times of tremendous hardship on the Great Plains. Settlers dealt not only with the Great Depression, but also with years of drought that plunged an already-suffering society into an onslaught of relentless dust storms for days and months on end. They were known as dirt storms, sand storms, black blizzards, and “dusters.” It seemed as if it could get no worse, but on Sunday, the 14th of April 1935, it got worse. The day is known in history as “Black Sunday,” when a mountain of blackness swept across the High Plains and instantly turned a warm, sunny afternoon into a horrible blackness that was darker than the darkest night. Famous songs were written about it, and on the following day, the world would hear the region referred to for the first time as “The Dust Bowl.”

The wall of blowing sand and dust first blasted into the eastern Oklahoma panhandle and far northwestern Oklahoma around 4 PM. It raced to the south and southeast across the main body of Oklahoma that evening, accompanied by heavy blowing dust, winds of 40 MPH or more, and rapidly falling temperatures. But the worst conditions were in the Oklahoma and Texas panhandles, where the rolling mass raced more toward the south-southwest - accompanied by a massive wall of blowing dust that resembled a land-based tsunami. Winds in the panhandle reached upwards of 60 MPH, and for at least a brief time, the blackness was so complete that one could not see their own hand in front of their face. It struck Beaver around 4 PM, Boise City around 5:15 PM, and

Singer-songwriter Woody Guthrie, who was born and grew up in Okemah, Oklahoma, moved to Pampa, Texas in 1931. Many of his early songs were inspired by his personal experiences on the Texas High Plains during the dust storms of the 1930s. Among them is the song “Dusty Old Dust,” which also became known as “So Long, It’s Been Good to Know Yuh.” In the original lyrics, he sings, “Of the place that I lived on the wild windy plains, in the month called April, county called Gray…” (Pampa was, and is, in Gray County .) Also among the lyrics:

“A dust storm hit, an’ it hit like thunder;

It dusted us over, an’ it covered us under;

Blocked out the traffic and blocked out the sun,

Straight for home all the people did run,

Singin’:

So long, it’s been good to know yuh;

So long, it’s been good to know yuh;

So long, it’s been good to know yuh.

This dusty old dust is a-getting’ my home,

And I got to be driftin’ along.”

class="summary"The lyrics are highly representative of the events of Black Sunday in the Texas panhandle, and suggest that Black Sunday may well have been the specific event that inspired those words more than any other.

Robert E. Geiger was a reporter for the Associated Press. He and photographer Harry G. Eisenhard were overtaken by the storm six miles from Boise City, Oklahoma, and were forced to wait two hours before returning to town. Mr. Geiger then wrote an article that appeared in the Lubbock Evening Journal the next day, which began: “Residents of the southwestern dust bowl marked up another black duster today…” Another article, also attributed to “an Associated Press reporter” and published the next day, included the following: “Three little words… rule life in the dust bowl of the continent – ‘if it rains’.” These cases generally are acknowledged to be the first-ever usages of the phrase by which the events of the 1930s have been known to history ever since: The Dust Bowl.

The blowing dust that blasted the High Plains in the 1930s was attributed not only to dry weather, but to poor soil conservation techniques that were in use at the time. In March 1935 (several weeks before Black Sunday), one of President Roosevelt’s advisors, Hugh Hammond Bennett, testified before congress about the need for better soil conservation techniques. Ironically, dust from the Great Plains was transported all the way to the East Coast, blotting out the sun even in the Nation’s capital. Mr. Bennett only needed to point out the window to the evidence supporting his position, and say, “This, gentlemen, is what I’ve been talking about.” Congress passed the Soil Conservation Act before the end of the year.

"Suddenly there appeared on the northern horizon a black blizzard, moving toward them; there was no sound, no wind, nothing but an immense 'boogery' cloud. Donald Worster, Dust Bowl – The Southern Plains in the 1930s. [From https://www.perryton.com/black.htm]

"Borger reported the storm struck at 6:15 PM; Amarillo at 7:20 PM; Boise City, Oklahoma, at 5:35 PM; and Dalhart at 5:15 PM." Ochiltree County Herald (Perryton TX), 18 April 1935. [Other reports suggest the actual time in Boise City was more likely 4:35 PM.]

"Some People Thought the End of the World was at Hand when Every Trace of Daylight was Obliterated at 4:00 PM." Liberal News, 15 April 1935.

"The Worst I Ever Seen." Northwest Oklahoman (Shattuck), 16 April 1935.

"Worst dust storm ever known in this country on 14 of April." Observer, Beaver OK.

"When dust obscures sun, is it 'cloudy?'" Observer, Pampa TX.

"...A huge cloud of black top soil swooped down upon Laverne in the manner of a heavy cloud flattening out upon the earth and spread absolute darkness the like of which has never been experienced by most Harper county folk." The Leader Tribune, Laverne, 18 April 1935.

"...a great black bank rolled in out of the northeast, and in a twinkling when it struck Liberal, plunged everything into inky blackness, worse than that on any midnight, when there is at least some starlight and outlines of objects can be seen. When the storm struck it was impossible to see one's hand before his face even two inches away. And it was several minutes before any trace of daylight whatsoever returned." Liberal News, 15 April 1935.

"The billowing black cloud struck Amarillo at 7:20 o'clock and visibility was zero for 12 minutes." Amarillo Daily News, 15 April 1935 (from the Associated Press).

"Mr. Williamson... had mounted a horse and was headed toward the fire when he met this great dust cloud, and was enveloped in darkness. The electrical current was so strong that it snapped from ear to ear on his bronco, and the cow chips ignited by the fire would roll hundreds of yards kindling the grass as they rolled and burned." Panhandle Herald, Guymon, 15 April 1935.

"Now, as we recall that day, we are glad that we were eye-witnesses to perhaps the most awe-inspiring and majestic upheaval of Nature that ever occurred in this section of the United States." Pauline Winkler Grey, The Black Sunday of April 14, 1935. Kansas Historical Society.

"The wind was travelling at a speed of sixty miles an hour; when it struck, visibility was reduced to zero for a period of twenty minutes, after which time visibility was limited to ten feet or less, lasting for forty-five minutes, then visibility increased to fifty feet or more at sporadic intervals and thereafter gradually increasing until normal nightfall." U. S. Government Weather Bureau at Dodge City KS. From The Black Sunday of April 14, 1935. Kansas Historical Society.

"It was as though the sky was divided into two opposite worlds. On the south there was blue sky, golden sunlight and tranquility; on the north, there was a menacing curtain of boiling black dust that appeared to reach a thousand or more feet into the air. It had the appearance of a mammoth waterfall in reverse – color as well as form. The apex of the cloud was plumed and curling, seething and tumbling over itself from north to south and whipping trash, papers, sticks, and cardboard cartons before it. Even the birds were helpless in the turbulent onslaught and dipped and dived without benefit of wings as the wind propelled them. As the wall of dust and sand struck our house the sun was instantly blotted out completely. Gravel particles clattered against the windows and pounded down on the roof. The floor shook with the impact of the wind, and the rafters creaked threateningly. We stood in our living room in pitch blackness. We were stunned. Never had we been in such all-enveloping blackness before, such impenetrable gloom." Pauline Winkler Grey, The Black Sunday of April 14, 1935. Kansas Historical Society.

"Tommy Peckham lost his way in the storm and stopped to knock on a door. 'Mr. (Loefbourrow),' he said, 'This is Tommy Peckham and I'm lost. May I come in?' He was at home and didn't know it. Forgan Advocate, 18 April 1935.

"Residents of the southwestern dust bowl marked up another black duster today and wondered how long it would be before another one came along." Associated Press, Lubbock Evening Journal, 15 April 1935. (Probably written by Robert Geiger; may be the first appearance of "dust bowl.")

| Liberal KS | 4:00 PM (Liberal News; from NE) |

| Alva (10 S) | 4:00 PM ("about;" Texhoma Times) |

| Beaver | 4:00 PM ("about;" Forgan Advocate, 18 April 1935; from N) |

| Harper Co. OK | 4:00-4:30 PM (Harper County Journal; north wind) |

| Laverne | 4:20 PM (Leader Tribune, Laverne, 18 April 1935) |

| Hooker | 4:30 PM (observer) |

| Woodward | 4:30 PM (Daily Oklahoman) |

| Medford | 4:50 PM (Grant County Journal; from NW) |

| Shattuck | 5:00 PM (Northwest Oklahoman) |

| Arnett | 5:00 PM (observer) |

| Vici | 5:00 PM (Vici Beacon, 18 April 1935; from N) |

| Perryton TX | 5:00 PM (Ochiltree County Herald; from N) |

| Canadian TX | 5:00-6:00 PM |

| Boise City | 5:15 PM (Boise City News, 18 Apr 1935), 5:35 PM, (Ochiltree County Herald) |

| Spearman | 5:15 PM (observer; from NE) |

| Dalhart | 5:15 PM (Ochiltree County Herald) (5:55 PM or 85 min. before Amarillo - Amarillo Daily News) |

| Kenton | 5:20 PM (Boise City News, 18 Apr 1935) |

| Waukomis | 5:30 PM (observer) |

| Stratford TX | 5:40 PM (observer) |

| Hammon | 5:45 PM (Daily Oklahoman; from NW) |

| Texhoma | 5:45 PM (Texhoma Times, 18 April 1935; from NE) |

| Camargo | 6:00 PM (observer) |

| Hennessey | 6:00 PM (observer; from NW) |

| Kingfisher | 6:00 PM (observer) |

| Borger TX | 6:15 PM (Ochiltree County Herald) |

| Stinnett TX | 6:35 PM (45 min. before Amarillo; Amarillo Daily News) |

| Erick | 7:00 PM (observer) |

| Oklahoma City | 7:15 PM (Daily Oklahoman) |

| Amarillo | 7:20 PM (Ochiltree County Herald; Amarillo Daily News; Northwest Oklahoman |

| Wichita Falls | 9:45 PM (Amarillo Daily News) |

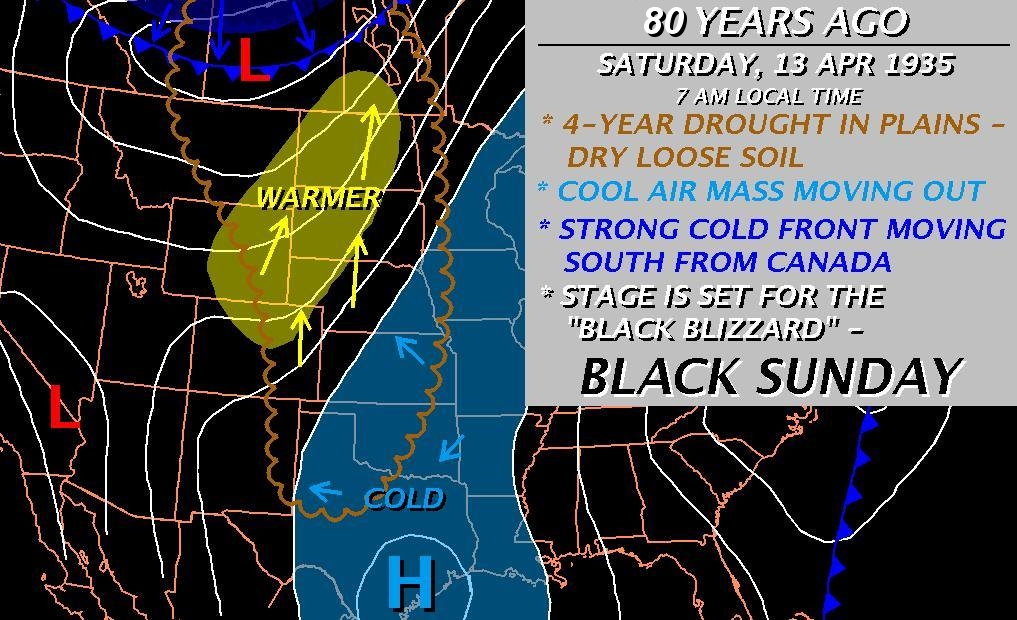

NWS Norman Graphicast Depicting the Surface Weather Conditions at 7:00 am CST on April 13, 1935

NWS Norman Graphicast Depicting the Surface Weather Conditions at 7:00 am CST on April 14, 1935

NWS Norman Graphicast Depicting the Surface Weather Conditions at 6:00 pm CST on April 14, 1935

U.S. Weather Bureau Surface Analysis at 7:00 am CST (1300 UTC) on April 13, 1935. Map Credit: NOAA Central Library Data Imaging Project. Daily Weather Maps, 13 April 1935.

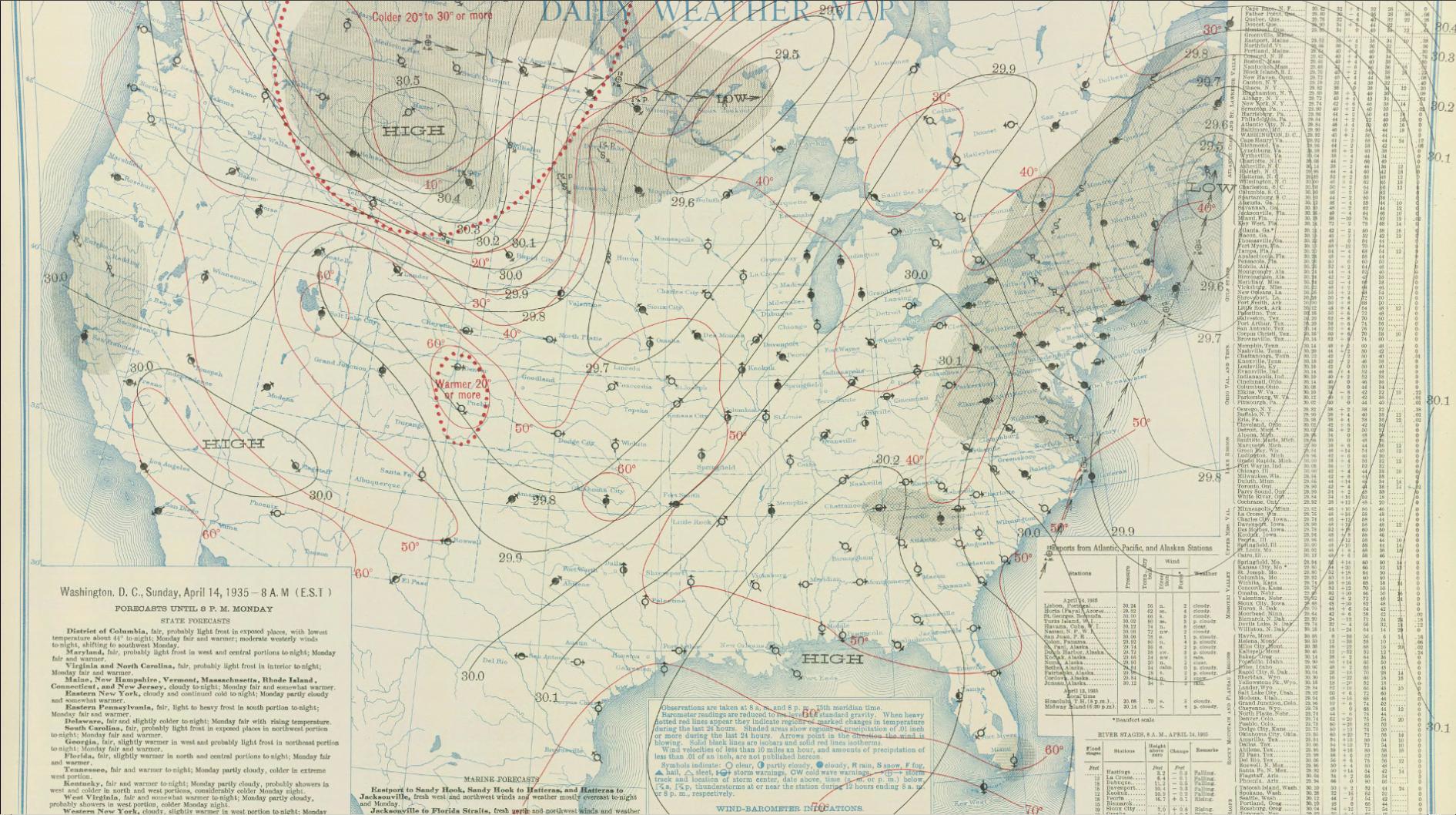

U.S. Weather Bureau Surface Analysis at 7:00 am CST (1300 UTC) on April 14, 1935. Map Credit: NOAA Central Library Data Imaging Project. Daily Weather Maps, 14 April 1935.

U.S. Weather Bureau Surface Analysis at 7:00 am CST (1300 UTC) on April 15, 1935. Map Credit: NOAA Central Library Data Imaging Project. Daily Weather Maps, 15 April 1935.

This is an image of a typical monthly report form circa 1935. The form is the USWB monthly cooperative observer form from the observer in Arnett, OK for April 1935.

The Black Sunday dust storm located near Beaver, Oklahoma on 04/14/1935. Source: The National Archives

The Black Sunday dust storm approaching Liberal, Kansas on 04/14/1935. Source: The National Archives

The Black Sunday dust storm approaching Rolla, Kansas on 04/14/1935. Source: The National Archives

The Black Sunday dust storm approaching Spearman, Texas on 04/14/1935. Source: The National Archives

The Black Sunday dust storm approaching Spearman, Texas on 4/14/1935. In: "Monthly Weather Review," Volume 63, April 1935, p. 148. Source: NOAA Photo Library

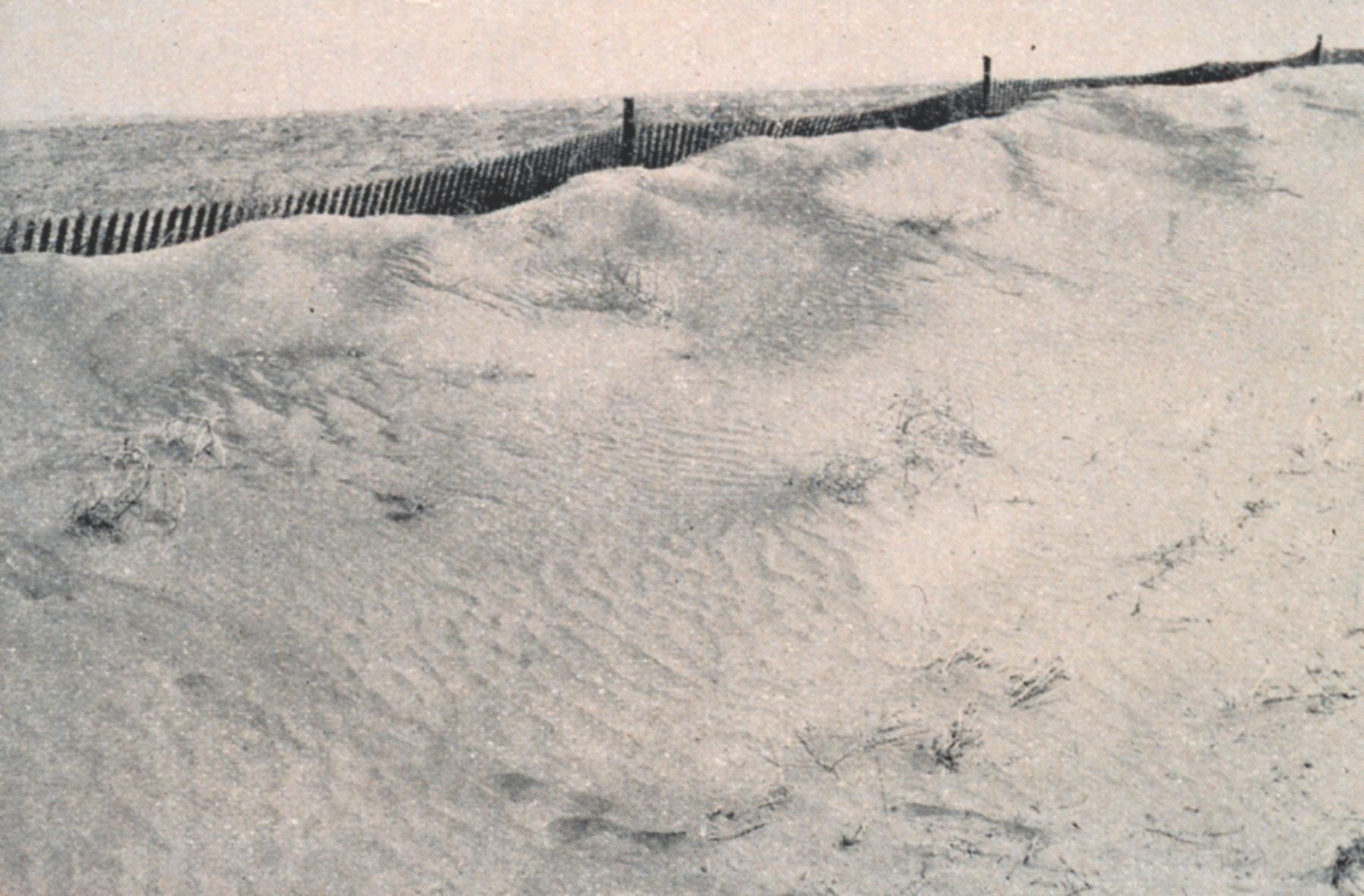

Dust and sand heaped up against fence windbreak. "Local drifting began almost imperceptibly and finally merged with regional blowing."Prior to the 1930's there had been a number of episodes of dust storms occurring in the Dust Bowl area. In: "Erosion and Its Control in Oklahoma Territory," Angus H. McDonald, Misc. Publication No. 301, Department of Agriculture. 1938. Figure 2. S21.A46. Source: NOAA Photo Library

Dust buried farms and equipment, killed livestock, and caused human death and misery during the height of the Dust Bowl years. In: "Monthly Weather Review," June 1936, p.196. Source: NOAA Photo Library

Photo # 1 of sequence. Garden City at 5:15 p.m. Note street lights and compare to photo 2 to orient picture. In: "Effect of Dust Storms on Health," U. S. Public Health Service, Reprint No,. 1707 from the Public Health Reports, Vol. 50, no. 40, October 4, 1935. Source: NOAA Photo Library

Photo # 2 of sequence. Garden City approximately 15 minutes later after dust storm blotted out the sun. Street lights are on allowing orientation of picture . In: "Effect of Dust Storms on Health," U. S. Public Health Service, Reprint No,. 1707 from the Public Health Reports, Vol. 50, no. 40, October 4, 1935. Source: NOAA Photo Library