|

| Introduction | Meteorology | Lasting Legacy | More Information |

Introduction

April 11, 1965 is known as the Palm Sunday Outbreak. The first tornado of the day touched down near Tipton, IA around 12:45 pm CST with the final tornado hitting near Toledo, OH at 9:30 pm EST. This outbreak ranks as one of the deadliest in recorded history with 271 fatalities and over 3400 injured. The financial impact of this outbreak was staggering: $200 million (1965) = $1.5 billion (2015). Other notable outbreaks include the 1925 Tri-State tornadoes (695 fatalities; only 8 documented tornadoes), the April 3-4, 1974 “Super Outbreak” (335), and the April 27, 2011 “Dixie Outbreak” (313).

Palm Sunday 1965 tornado tracks. Courtesy: Dr. Russell Schneider, SPC

Four confirmed tornadoes touched down in northern Illinois on April 11, 1965. The first Illinois tornado of the day formed around 3 pm CST northwest of Rockford, IL and moved northeast striking Rockton, IL. The tornado was relatively weak and did little damage; it blew over several airplanes and damaged a restaurant. The tornado was on the ground for 14 miles with a path width of 1/8 mile. Thankfully, most of the damage swath was confined to rural countryside.

Dr. Ted Fujita’s damage swaths of northern Illinois tornadoes following aerial survey.

The worst Illinois tornado of the day formed near Crystal Lake at 3:27 pm near the Crystal Lake Country Club where it uprooted some trees on the golf course. From there the tornado widened to roughly 1300 feet (~¼ mile) as it crossed Nash Street, causing severe damage to several homes. The storm continued across McHenry Avenue near Lee Drive, damaging houses along the way. The tornado destroyed a barn shortly after crossing Highway 14 and claimed the life of Rae Goss. Further damage occurred at the Lake Plaza Shopping Center, Piggly Wiggly Supermarket, and Neisner Department store.

The Colby Homes Estates subdivision was especially hard hit. Over 150 homes in the neighborhood were heavily damaged and another 45 destroyed. Unfortunately, the storm claimed four lives in the subdivision - Louis Knaack, Richard Holter, Rosalie Holter, and John Holter.

The tornado continued toward the community of Island Lake, IL where it caused extensive tree and vegetation damage. The storm first hit the west side of Island Lake along Illinois 176 around 3:37 pm. Homes in the area suffered extensive damage, along with boats and piers along the lake. A five year old boy was killed when a home collapsed along the shore of Island Lake, the last casualty of the outbreak in Illinois. Eventually the tornado dissipated near Highway 12 over open countryside at 3:42 pm.

Later, the tornado would be rated an F4 based upon the damage done in McHenry and Lake Counties (What is the F/EF scale?) with estimated winds of 207-260 mph.

At 3:50 pm the third Illinois tornado touched down near Druce Lake in Lake County. The tornado tracked to the northeast, crossed Interstate 94, and lifted near the Waukegan Airport. Several homes along the path were damaged while hangars and airplanes were heavily damaged at the airport. The tornado was only on the ground for 4 miles before lifting and was later classified an F2 (113-157 mph).

Just after 4 pm the final Illinois tornado touched down near Geneva-St. Charles, IL and damaged a dozen homes near U.S. 30. This tornado was relatively weak and short-lived (path length under ½ mile).

While the damage was over in Illinois, the storms raced eastward wreaking havoc on communities across Indiana, Michigan, and Ohio.

Meteorology

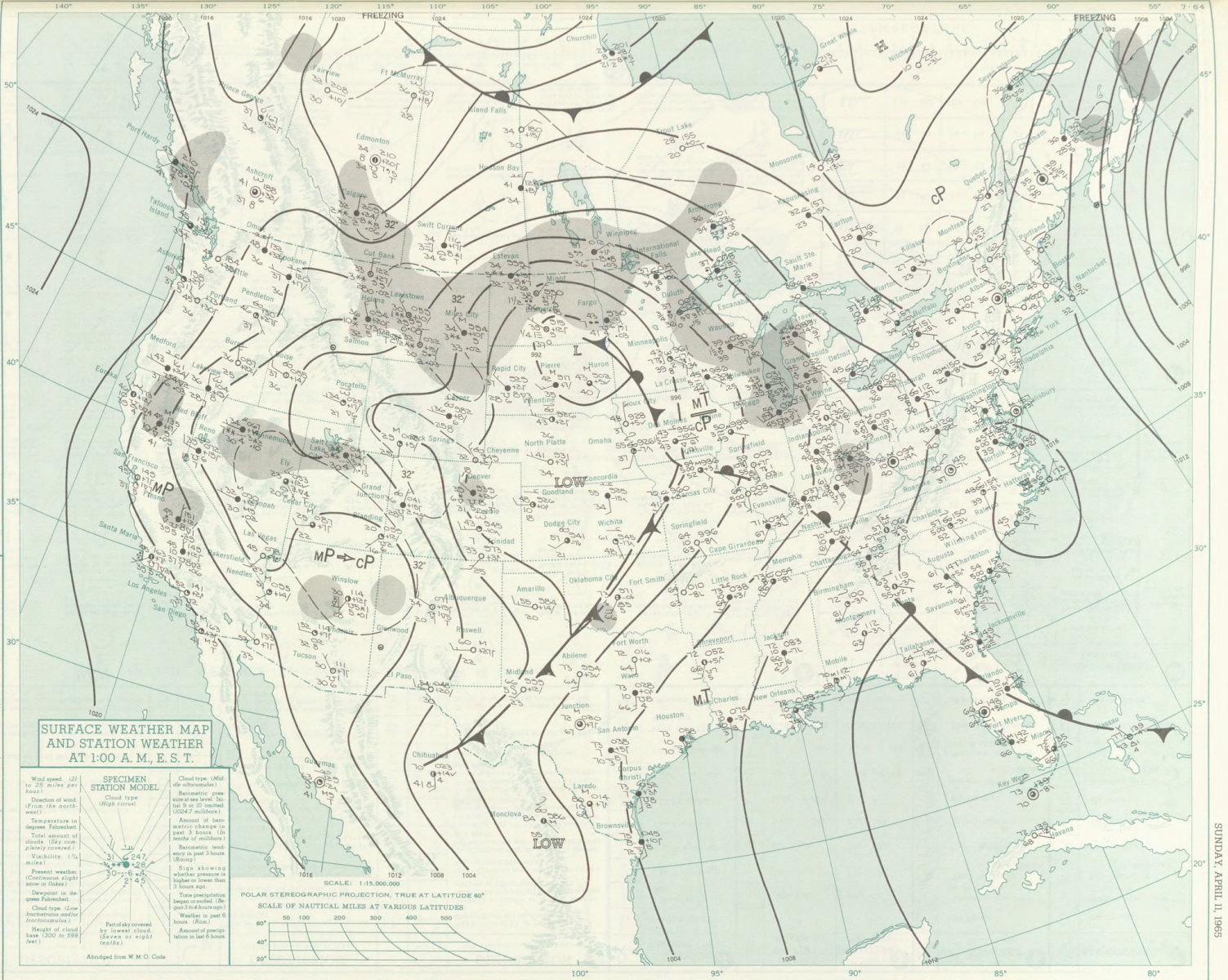

Palm Sunday 1965 marked the first truly warm day of spring for residents in the Midwest. Temperatures soared into the 70s accompanied by dewpoints in the 60s -- a very balmy Sunday across the Midwest.

A potent jet streak was observed by radiosondes at 6 am that morning, indicative of a strong spring weather system. The evening observations showed the jet had strengthened with winds aloft generally on the order of 122 knots (~140 mph) with a jet max observed near Dodge City, KS of 159 knots (~183 mph)! The intense jet streak brought steep mid-level lapse rates (rapid temperature decreases with height) into the Midwest. These lapse rates were advected atop a very warm, moist layer in the lower levels of the atmosphere creating widespread instability to drive intense thunderstorms.

%2011%20April%201965.gif)

500 mb chart at 6pm CST April 11, 1965. Notice intense jet streak over the Central Plains.

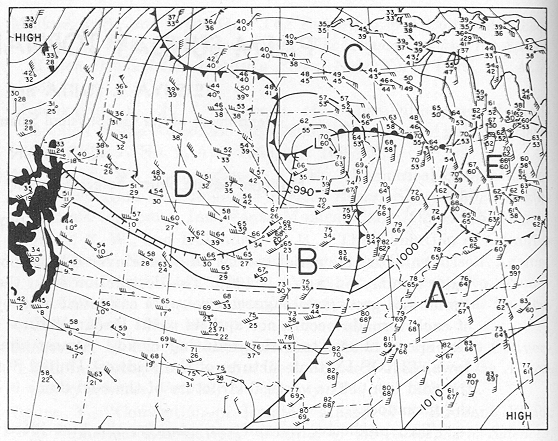

A strong low pressure system had pushed into central Iowa by noon, deepening to 985 mb. Along with the low, a warm front surged northward into lower Michigan with southerly winds advecting warm, moist air into the region, further destabilizing the atmosphere. Dr. Ted Fujita’s detailed surface analyses of this day show the progression of the system throughout the day.

|

|

By 11 am storms had formed primarily along the warm front across eastern Iowa and northern Illinois. The cold front extended south of the low pressure center along the tightly packed isodrosotherms. Following the event, many people described the unusually warm, strong southerly winds that afternoon, which by 3 pm CST (15 CST) were gusting to near 30 mph ahead of the cold front. Simultaneously, a line of supercell thunderstorms had formed across northern Illinois and southern Wisconsin by this time; this line of storms produced the Crystal Lake tornado 30 minutes later. Within 2 hours the storms had raced eastward out of northern Illinois and winds had shifted to west-southwesterly with much drier air filtering into the region.

Solid black lines indicate lines of equal pressure, the dashed lines are dew points (isodrosotherms), and wind barbs. Full barbs = 5 knots (~6 mph), darkened flags = 25 knots (~29 mph). The dark, hatched blobs represent radar returns of the storms in progress.

The cold front continued its eastward track into Michigan, Indiana, and Ohio where tornadoes continued to ravage communities across the region until just after sunset. Unfortunately, the majority of fatalities associated with the outbreak occurred in these three states: 145 in Indiana, 53 in Michigan, and 60 in Ohio. Perhaps the most well known of these tornadoes was the twin funnel tornado that struck near Dunlap, IN and was captured in a series of photographs by Elkhart Truth reporter Paul Huffman.

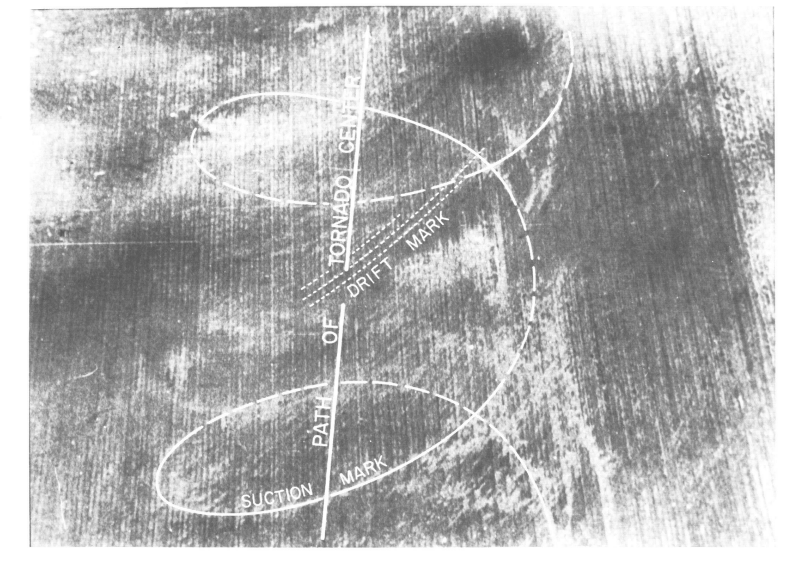

Following the outbreak, Dr. Fujita realized that the occurrence of many storms over such a large area made the event worthy of special effort to collect data. Dr. Fujita chartered an airplane and conducted a thorough aerial survey of the damage path (his survey can be found here). Following this survey, Fujita noticed peculiar marks along many of the damage swaths. Fujita had discovered suction vortices. Suction vortices are small, intense “mini-tornadoes” within the main tornado (a recent example would be the El Reno, OK tornado May 31, 2013). These suction vortices helped to explain why one structure may be destroyed but the adjacent structure is left standing. Suction vortices continue to be of great interest to tornado researchers.

Aerial photograph of typical suction and drift marks left by a tornado on an unplowed field.

Lasting Legacy

The Palm Sunday Outbreak of 1965 has left a lasting legacy that persists to this day. Following the event, the U.S. Weather Bureau (now the National Weather Service) convened a survey team to investigate all facets of the outbreak. The survey team’s report outlined several recommendations that would better prepare forecasters and the general public for future high-impact weather events. These recommendations are still relevant and continue to evolve today.

Transforming the Warning Process

In 1965 the Severe Local Storms Unit (SELS), known today as the Storm Prediction Center (SPC), issued tornado forecasts if conditions were favorable for tornadoes or a tornado warning if a tornado had been positively identified. The survey team learned that many people were confused about the difference; they simply thought a warning was an “update” to the tornado forecast. To help prevent confusion the term “tornado forecast” was changed to “tornado watch,” a term still in use to this day. Additionally, given that many people were outside enjoying the warm weather, people had no means to obtain the tornado warnings that were issued that day. In response, many communities repurposed their Civil Defense sirens to be used as an outdoor warning mechanism.

| The Palm Sunday Outbreak tornado forecasts from SELS. Boxes indicate areas under the forecast and inverted triangles represent reported tornadoes. | |

The tornado warning process continues to evolve and the Integrated Warning System created by the NWS is a means to improve this process. This system emphasizes the synthesis of the forecast, detection of hazards, quick and proper dissemination of relevant information, and public response. Each aspect is fundamental to a successful warning process, the goal of which is to mitigate loss of life. The Palm Sunday Outbreak made it painfully clear that an improved warning system needed to be developed; an emphasis that persists 50 years later.

Storm Spotters

Another finding from the survey team was the need for ground truth observations. Ground truth observations can make the difference between a lifesaving warning and a false alarm. One such source of these observations was storm spotters. Storm spotters had existed prior to the event but were widely scattered and unorganized. The survey recommended that Weather Bureau (WB) offices place greater emphasis on fostering the formation and education of spotter networks in their areas. This emphasis eventually resulted in the formation of SKYWARN, a volunteer organization that provides accurate and timely severe weather reports to WB offices. Today there are over 290,000 trained SKYWARN spotters, a far cry from the few hundreds (at most) in 1965.

Amateur Radio

Sprouting out of the emphasis on creating a well-educated spotter network, the influence of amateur radio helped fuel the increasing effectiveness of spotters and ground truth observations. Merle Kachenmeister (WA8EWW), a forecaster with the Toledo WB office, formed the “Tri-State Weather Network,” a HAM radio network that reported observations, forecasters, and other relevant weather information to the WB and others within the network. By the end of 1966 other networks had sprung up across the country with enthusiastic support from Civil Defense and individual Weather Bureau offices.

NOAA Weather Radio

NOAA Weather Radio did not exist as we know it today in 1965. The network had only 50-60 stations that provided weather forecasts primarily for aviation and marine interests. However, tone alerts had been implemented that would activate the receiver when a tornado warning had been issued, providing another source of warning information for the general public. Following the Palm Sunday Outbreak the number of stations gradually began to increase in response to the event. By the time of the famous Super Outbreak April 3-4 1974 there were approximately 125 stations in operation. Today, there are over 1025 stations covering 97% of the United States and provide another outlet for receiving weather information in a timely manner.

NOAA Weather Wire

A recommendation of the survey team was the efficient distribution of warnings and forecasts. Due to congested communication lines and power outages, many warnings were not properly transmitted. Until the 1965 Palm Sunday outbreak, tornado warnings were disseminated from the WB to local radio and TV through teletype circuits and phone lines. In response, the NOAA Weather Wire was created to alleviate dissemination issues by providing a means for warnings to be transmitted quickly regardless of power outages or heavy usage. This process allowed for broadcast meteorologists to quickly inform their audience of any impending extreme weather. Today, weather warnings and information are transmitted via satellite communication, ensuring rapid delivery across the country.

Increased Collaboration across Weather Industry

Protecting lives and livelihoods require a collaborative effort. The survey team recognized this as a critical component in the dissemination of weather information to the public. Without proper collaboration among the NWS, emergency managers, broadcast media, private meteorology, and first responders, the goal of protecting lives is compromised. The Weather Ready Nation initiative encapsulates the goal of increased collaboration into one mechanism that can reach many individuals.

Public Preparedness

Implicit in the Weather Bureau’s report was the need for increased public awareness. Many individuals interviewed following the outbreak expressed confusion over terminology or a lack of awareness regarding the threat tornadoes posed to their area. The survey team tasked the Weather Bureau with ensuring that the public was educated and prepared for weather disasters in an effort to save lives.

The legacy of the Palm Sunday 1965 Outbreak persists to this day in the effort to ensure the safety of individuals in the path of hazardous weather. The tornado event in northern Illinois April 9, 2015 is an example of the legacy of 1965 in action. Warning information was quickly disseminated via social media, reaching thousands of people in the warning area. Social media outreach is yet another step in the Integrated Warning System that allows warnings to quickly reach those in the path. Additionally, storm spotters on that day were integral in getting crucial information on the storm evolution to the forecasters. This influx of information allowed the forecasters to quickly tailor warning information to include ground truth observations. The April 9th event, and all other events like it, illustrates the lasting impact the Palm Sunday Outbreak had on the meteorological community. The impact of the outbreak endures as the weather community continually seeks to improve knowledge of severe weather, its impacts on society, and how to best warn and protect against those impacts.

For more information on the 1965 Palm Sunday Outbreak please visit:

NWS Northern Indiana

NWS Detroit

NWS Grand Rapids

NWS Indianapolis

Crystal Lake Historial Society

2015 Fermilab Tornado Seminar

NWS Chicago MIC Edward Fenelon

Tom Skilling on the famous twin funnel picture

Article by Shane Eagan, WFO Chicago Student Volunteer, April 2015