|

February 3rd/4th: The Ice Storm Cometh

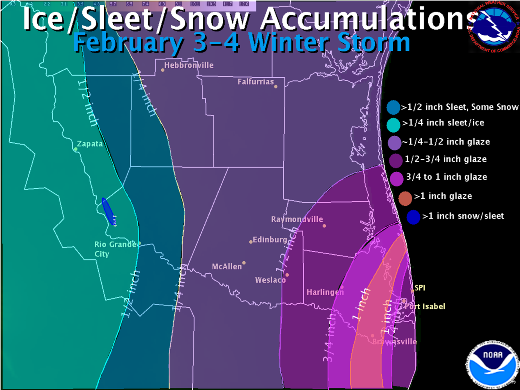

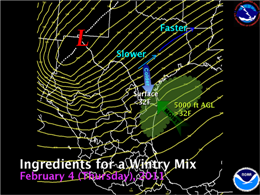

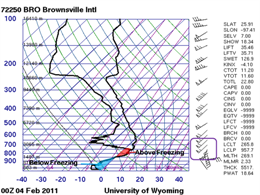

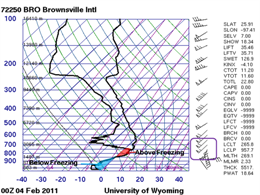

Just a day after arctic air plunged the Valley into the freezer, the approach of an upper level disturbance (below, left) lifted a limited amount of low level moisture into light precipitation, starting by mid morning in Cameron and Willacy County, spreading into Hidalgo County during the afternoon and eventually across all of Deep South Texas by evening. Frigid, sub freezing temperatures settled throughout the region, and saturation levels began lowering toward the ground. At the same time, increasing southerly winds just a few thousand feet above the surface raised temperatures above freezing, between around 5 and 12 thousand feet (1500 and 3700 meters). A pocket of this layer between 5700 and 8100 feet was saturated, ensuring a mix of rain freezing on contact with the ground, and ice pellets (rain re–freezing before contact with the ground) as the primary precipitation types (below, right).

The low clouds and developing freezing and frozen precipitation ensured little change in temperature during the daylight hours of February 3rd. Readings, which fell into the upper 20s in most areas by daybreak, remained in place where precipitation developed early, and only rose to the freezing point (32°F) where precipitation developed by evening. Every location in Deep South Texas had at least 30 hours at or below 32°F. For a second day, the combination of stiff north winds and low air temperatures made it feel like the teens for most areas. Check out the map of February 3rd minimum temperature and wind chill, and the February 3rd temperature table, showing minimum, maximum, and highest daytime temperature.

The combination of freezing drizzle and light freezing rain, sleet, and even a brief snow band continued overnight on the 3rd, as temperatures remain planted in the upper 20s to around 30. The precipitation began ending from west to east after midnight, but not before producing a quick band of more than an inch of snow downwind of Falcon International Reservoir shortly after midnight on February 4th. Click here for an image of the snow band, highlighted in turquoise. The upper level disturbance moved into central Texas during the morning, ending the precipitation across the Rio Grande Plains/Upper Valley/Brush Country counties of Starr, Zapata, and Jim Hogg County before daybreak, Hidalgo and Brooks County by 8 AM, and Kenedy through Cameron Counties between 9 and 11 AM. Temperatures would briefly fall into the lower 20s across the Rio Grande Plains before quickly rising above freezing by mid morning. Farther east, where clouds were last to move out, temperatures would rise above freezing between 10 and 11 AM, with all areas out of the freeze by noon. Ample sunshine despite a chilling breeze would melt the ice by mid afternoon on the 4th. The February 4th temperature table shows the morning chill and afternoon recovery.

Impacts from the Ice Storm

The beauty of the ice did not come without some consequences. The rare and dangerous chill required the opening of dozens of shelters and a few warming centers across the Valley, where hundreds of residents without sufficient heat spent a night or two. The immediate buildup of a glaze on elevated surfaces forced the closure of all such roadways in the region, as crews used a combination of gravel, salt, sand, and ash to provide traction for emergency vehicles. Unfortunately, icy roads took human casualties, and scattered to locally numerous power outages were common. Despite the impacts, early warning and ample preparedness by communities mitigated what could have been substantially higher suffering at the hands of the rare ice storm – one that has not been experienced in decades, if not longer. The National Weather Service in Brownsville praises the efforts of local emergency management, transportation, public health, utility companies, and the media for spreading the word and making a molehill out of a potential mountain.

The following is a compilation of general impacts throughout the ice storm. Details, as we received them, can be found here. Some information below was provided by The McAllen Monitor, The Brownsville Herald, and The Valley Morning Star.

- Accidents. Local first responders noted a total of 194 vehicle crashes during the event across the Lower Rio Grande Valley. One of the accidents left a man dead and two others critically injured from a rollover along State Highway 186 east of Raymondville (Willacy County). Another 20 persons were admitted to the McAllen Medical Center for a variety of minor injuries from crashes in Hidalgo County.

- Falls. Sidewalks, driveways, and other surfaces became slick in some areas after midnight on the 4th, continuing through early morning. Emergency Rooms noted a number of incidents of serious bruises, tailbone injuries, and sprained elbows and wrists.

- Power Outages. At least 65,000 customers were without electricity at the peak of the event early on the 4th. This included more than 63,000 AEP Texas customers and 275 Brownsville PUB customers. The majority of outages were due to rolling brownouts, triggered by the Electric Reliability Council of Texas.

- Road Closures. During the peak of the storm, all elevated highways across the Rio Grande Valley were closed, and motorists were diverted onto the wet pavement of frontage roads. A large number of low water bridges were also closed due to ice and a lack of sufficient treatment to ensure safety. Overnight on the 3rd and into the morning of the 4th, lesser traveled roads also saw icing.

- School and Business Closures. Nearly every primary independent school district closed in Cameron and Willacy County prior to the onset of glaze ice on February 3rd. Much of Hidalgo remained open to begin the day, with many closing early as conditions began to deteriorate toward sunset. All schools were closed for at least the morning of the 4th, and a number of businesses shuttered until at least noon.

- Agricultural Damage. Fortunately for most growers, the long duration freeze spared crops from significant damage. Two conditions were advantageous to citrus and other crops: Timing and Temperature. Most fruit had been picked prior to the freeze, and new growth of buds and blossoms had not begun. The small difference between daytime and nighttime temperatures minimized impact to the trees, and the shield of ice around leaves may have kept damage down. Other plants, such as vegetables and cotton, had not yet started their spring growth phase. The same could not be said for sugar cane, which sustained significant damage, with between one third and one half crop loss. The Texas A&M Agrilife Center reported some damage to early plantings of cabbage, watermelon, peppers, leafy greens, and tomatoes. Estimated damage and loss across the Lower Rio Grande Valley was between $10 and $15 million.

|

Graphic showing upper level disturbance (Red "L") moving into west Texas, helping draw sufficient moisture for precipitation above 5,000 feet above the ground, while subfreezing temperatures continue to race into the Valley. The blue arrows denote slower air in the jet stream moving toward faster air. The diverging air streams aloft produce some converging air near the surface, lifting moisture into clouds and precipitation.

|

Brownsville atmospheric sounding, completed at 6 PM CST February 3rd (Midnight Universal Coordinated Time February 4th). The red and blue shaded pattern is a classic sleet or freezing rain signal. Typically, a larger blue area indicates sleet, while a larger red area indicates freezing rain. Had there been just a bit more atmospheric lift late on the 3rd, most precipitation would have fallen as ice pellets in the Lower Valley. Instead, the tiny water droplets were able to reach ground before re–freezing, becoming glaze on contact.

|