lllinois' 3rd deadliest tornado disaster on record occurred on May 26, 1917. On that date, 108 people were killed across central Illinois, almost all in the Mattoon/Charleston area. Injuries totaled approximately 638. (Some confusion and duplication in the hardest hit areas resulted in some victims being double-counted for a time, thus the higher total shown in the Tribune headline in the above graphic.)

Originally, this was believed to be a single tornado with a path 293 miles long, extending from the Mississippi River across from Louisiana, MO, all the way across central portions of Illinois and Indiana, ending near Mount Vernon, IN, over a total time span of 7 hours 20 minutes. This was later determined to be 4 to 8 separate tornadoes; the Illinois portion was approximately 155 miles (including times it was aloft), over a time of approximately 4 hours. The strongest part of the tornado, through Mattoon/Charleston, was later determined to be F4 intensity on the original Fujita scale.

Originally, this was believed to be a single tornado with a path 293 miles long, extending from the Mississippi River across from Louisiana, MO, all the way across central portions of Illinois and Indiana, ending near Mount Vernon, IN, over a total time span of 7 hours 20 minutes. This was later determined to be 4 to 8 separate tornadoes; the Illinois portion was approximately 155 miles (including times it was aloft), over a time of approximately 4 hours. The strongest part of the tornado, through Mattoon/Charleston, was later determined to be F4 intensity on the original Fujita scale.

|

The morning surface map showed low pressure centered in northwest Iowa; this had moved to west central Illinois by evening. Showers and thunderstorms had been reported overnight across central Illinois. The forecast called for additional thunderstorms to develop during the afternoon. (Map courtesy of the NOAA Central Library Data Imaging Project) |

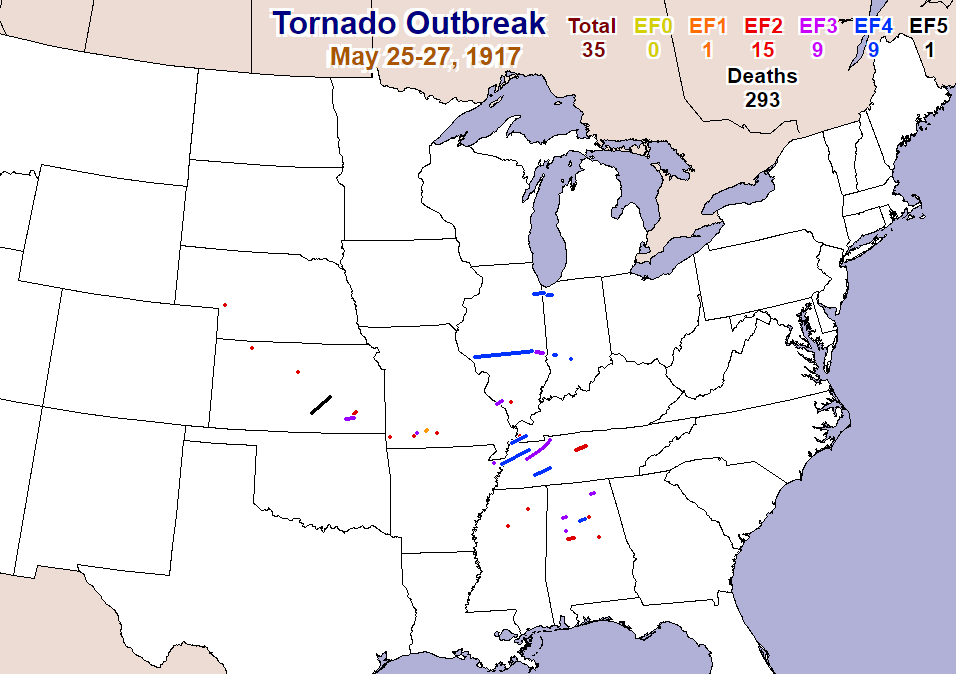

Overall, 383 people were killed over an 8 day period between May 25th and June 1st. At least 73 tornadoes occurred across the Midwest and Southeast U.S. during this time, with 15 that were classified as violent (F4 or F5 strength). The map at right, from the Storm Prediction Center, shows the tornadoes that occurred between May 25-27th.

Overall, 383 people were killed over an 8 day period between May 25th and June 1st. At least 73 tornadoes occurred across the Midwest and Southeast U.S. during this time, with 15 that were classified as violent (F4 or F5 strength). The map at right, from the Storm Prediction Center, shows the tornadoes that occurred between May 25-27th.

Archives of regional newspapers from 1917 were reviewed to compile this page. The Mattoon Journal Gazette, Decatur Herald, Decatur Review, and Chicago Tribune were most heavily used. Listings of the dead in the newspapers of the time were cross-referenced using cemetery records (specifically the Dodge Grove Cemetery and Find-a-Grave websites) and the statewide death index from the Illinois state archives. This resulted in a few adjustments to the casualty total from other references regarding this event.

Other references include:

If you have any contributions you would like to make this page, such as photos or stories, please send them to Chris.Geelhart@noaa.gov.

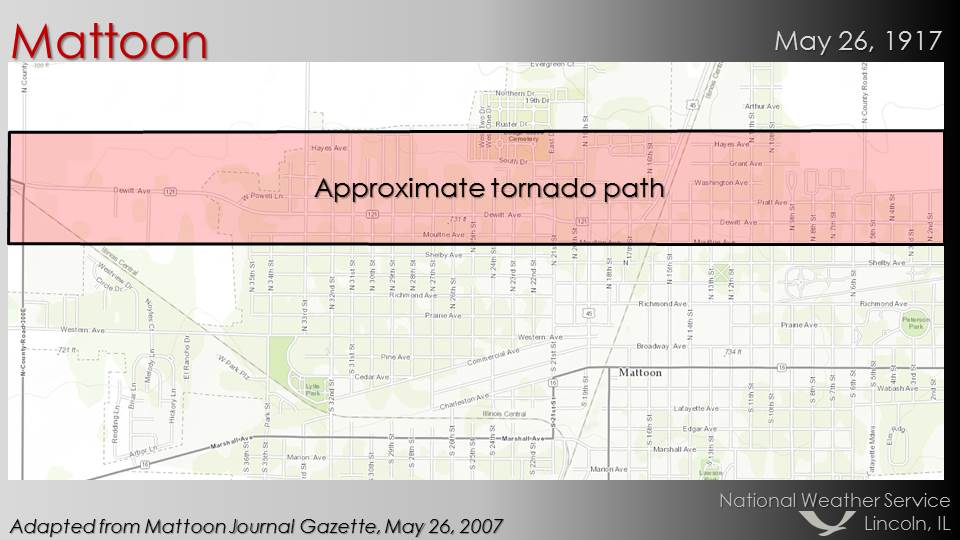

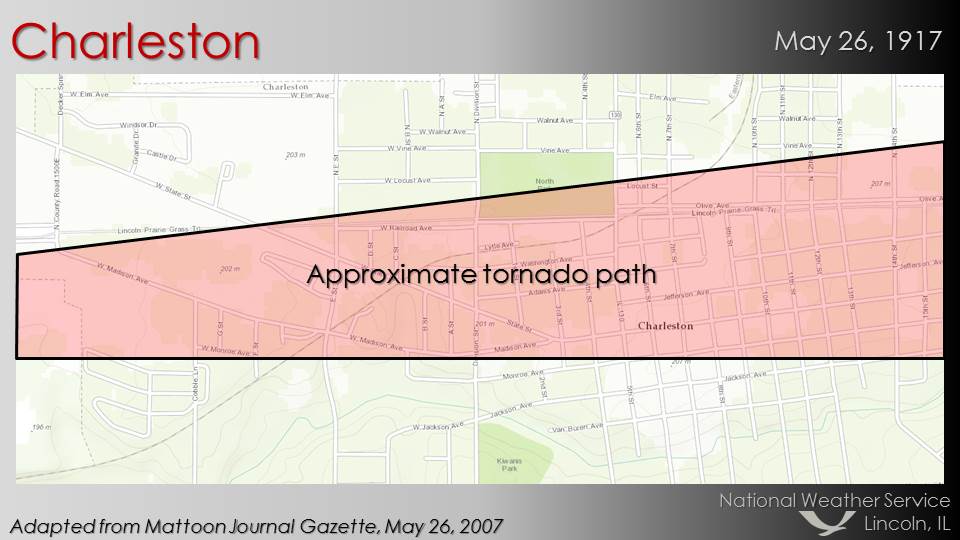

Intermittent contact with the ground was initially reported, before a steadier track began about 2 miles east of Nebo (southern Pike County) around 12:15 pm, where 5 people were injured. The tornado crossed northern Greene County and reached White Hall around 1 pm, then it was partially aloft until reaching Modesto, in northwest Macoupin County, around 1:30 pm. It crossed the narrow portion of Montgomery County northeast of Farmersville, then entered southern Christian County. It was partially aloft before touching down again west of Owaneco around 2:20 pm. Continuing on a nearly due east track and continuously on the ground, the tornado entered Shelby County and struck Westervelt at 2:50 pm. It crossed into far southern Moultrie County before entering Coles County. The tornado entered Mattoon around 3:25 pm, and after lifting for a brief time around Loxa, it reached Charleston around 3:45 pm. The most severe damage (and highest death toll) occurred in Mattoon and Charleston. Toward the end of the track, it curved northeast and dissipated near the town of Embarras; another tornado formed 5 miles southeast of Charleston and tracked southeast through Clark County, causing significant damage near Westfield and Marshall.

Click on the images below for an approximate track through each of these counties. The track maps were adapted from work by Wilson and Chagnon (1971) and Grazulis (1993).

| Time | Location | Casualties | Damage |

| 1 PM | White Hall (Greene County) |

3 injured | Damage to farm properties |

| 1:30 PM | Modesto (Macoupin County) |

3 killed, 20 injured | 30 homes destroyed, 35 badly damaged. Business district largely destroyed. |

| 2:20 PM | Owaneco (Christian County) |

1 killed | Many barns damaged or destroyed |

| 2:50 PM | Westervelt (Shelby County) |

6 killed, 25 injured | 10 homes and a church destroyed, 9 badly damaged. |

| 3:25 PM | Mattoon (Coles County) |

64 killed, 467 injured | 496 houses destroyed and 143 partially destroyed, leaving 2,500 homeless. Nearly every home in the northern half of town was damaged or destroyed. Near total destruction in a swath 2.5 miles long by 2.5 blocks wide. Damage estimates $1.3 million (1917 dollars). |

| 3:45 PM | Charleston (Coles County) |

34 killed, 182 injured | 221 homes destroyed and another 265 seriously damaged. Damage swath 1.5 miles long by 600 yards wide. Damage estimates $1 million (1917 dollars). |

The Mattoon/Charleston portion of the tornado track was surveyed by Clarence J. Root, the meteorologist in charge of the Weather Bureau office in Springfield. According to his report from the May 1917 edition of Climatological Data (shown on the last page at this link), the appearance of the tornado(es) changed over the course of the track:

| Across the State from the Mississippi River almost to Mattoon, all eye witnesses agree that the storm had the typical funnel-shaped tornado cloud with the swinging tail, and east of Charleston the same type of cloud was reported, but the writer, who visited Mattoon and Charleston, failed to find anyone in those cities who saw a funnel-shaped cloud. Eye witnesses who were near the edge of the city, and had an unobstructed view, agree that the approaching storm appeared as a low, boiling mass of clouds, one part a little to the north and the other a little to the south. The parts seemed to roll toward one another, coming together and downward like the meshing of a pair of cog-wheels. There was an abundance of evidence of true tornadic action, ... it might be suggested that the cloud was so low that there was no room for the usual pendant portion. |

According to a June 1st article by the Decatur Daily Review, Root spent 3 days surveying the damage. "The wonder to me is that not more people were killed," said Root.

The tornado passed a mile north of the Eastern Illinois Normal School (now Eastern Illinois University) in Charleston. There, barograph traces indicated the barometric pressure fell 0.27 inches, then immediately rose 0.40 inches, as the tornado passed. Winds were estimated to reach 80 mph, and hail of 2-1/4 inches in diameter was measured.

In early days, it was believed that tornado damage was caused by buildings "exploding" from the contrast in pressure. J.P. Carey, of the Department of Geography at the school, wrote the following in the June 15, 1917 edition of the journal Science:

| The reason for the location of the area of complete devastation being to the right of the center seems to be plausibly explained when the agents of destruction are considered. On the right of the center there is explosive action due to the reduced pressure on the outside of the buildings, the eastward component of the counter-clockwise wind of the tornado (probably over 400 miles per hour), the forward movement of the storm, and the west wind which was prevalent at that time all working in conjunction as agents of destruction... |

Of course, later research determined that the wind speed in tornadoes does not reach as high as 400 mph, but much was unknown about tornadoes and meteorology in general at the time.

In Mattoon, the tornado arrived around 3:25 pm. Clarence Root, the meteorologist in charge of the Springfield Weather Bureau office, reported that eyewitnesses on the edge of town described the storm as a "low, boiling mass of clouds" with no funnel clearly visible. However, according to the June 4th edition of the Mattoon Journal Gazette, one witness about 3 miles north of town described seeing "3 distinct funnels," and several other witnesses indicated two storm centers seemed to merge. (It is possible this may have been a multi-vortex tornado, but not enough evidence exists to make such a determination.)

The northern half of the town (largely everything north of DeWitt Ave.) was severely affected, with nearly every home damaged or destroyed in a swath 2.5 miles long by 2.5 blocks wide. A total of 496 houses were totally destroyed, and 143 were severely damaged, with damage estimates around $1.3 million (in 1917 dollars). Survey results indicated that this particular part of town consisted of cottages or small dwellings with no basements. The tornado struck a lumberyard, and flying wood from it struck a number of people that were caught outside. The main business district was largely unscathed by the storm, but did have broken windows and some tree damage. However, the T.W. Clark Manufacturing company was severely damaged, with damage estimates at $200,000. The storm also impacted Dodge Grove Cemetery (ironically, the final resting place of many of the tornado victims), overturning hundreds of grave markers and demolishing a mausoleum. However, the dwelling of the cemetery sexton remained standing, although significantly damaged.

The Journal Gazette, in the May 28th edition, noted that the tornado occurred one day before the anniversary of the 1896 St. Louis-East St. Louis tornado, which killed 255 people (140 in Illinois).

In Report of Tornado Disaster, written in 1918, it was written that "the storm literally swooped upon the city with a whirl and a whistle which reminded one of the onward rush of lumbering freight trains in mass formation."

Initial reports significantly inflated the casualties due to the general chaos after the storm. However, a total of 64 people were killed, and 467 people were injured. With nearly 2,000 people made homeless due to the storm, survivors stayed with friends, in public buildings, or in a tent refuge set up in Peterson Park, where 600 tents were sent from Springfield. The injured were treated at the local hospital, as well as a temporary operating room set up in a hotel; they were also treated at the library and various churches and schools. In the following days, carloads of food and clothing were sent from as far away as Indianapolis.

Fires broke out in parts of town, but were put out without serious damage.

The Chicago Tribune reported on the immediate aftermath:

| Every available vehicle in the city tonight was in service carrying the dead and injured to hospitals, churches and other public places left standing. Mattoon was in complete darkness except for the light of hundreds of lanterns carried by volunteer rescue workers, and not until daylight can the full number of casualties be known. A heavy hail storm which followed the wind hampered the work of rescue. |

Members of the 4th Illinois Infantry were sent to assist local first responders. This included the machine gun company and Company G from Effingham, Company M out of Champaign, Company C from Sullivan, and Company H out of Shelbyville, a total of nearly 260 people. They were ordered to keep out trespassers and were armed with loaded rifles. Before they arrived, a group of 250 local men patrolled the area, and subdued the initial looters; the soldiers took over Sunday, May 27th.

Doctors and nurses were brought in via train from Pana, Champaign, Carbondale, and other cities to assist with the medical needs of the area. Local officials feared an epidemic of contagious diseases due to unsanitary conditions, and 3 people were quarantined after being diagnosed with smallpox; several cases of measles and typhoid were also found. However, in general, the fears were not met.

At a special school board meeting on Monday, May 28th, it was decided to end the school year immediately, about a week ahead of schedule and without benefit of final exams. Graduations were also cancelled. Washington School was most severely damaged of the public schools.

Another severe storm moved across the area the evening of Wednesday, May 30th. The Journal Gazette reported that many citizens were panic-stricken that another tornado was on its way, and that some of the injured in hospitals had to be forcibly restrained. A brief tornado touchdown apparently did occur in an area bounded by Broadway, Charleston, 5th and 6th Streets, doing considerable damage in that area.

The following Mattoon residents perished as a result of injuries from the storm:

| Died May 26th | Died After the Storm |

|---|---|

|

|

One of the victims was the oldest resident of the city, Martha Smith. A former slave, she suffered a skull fracture and died of her injuries on May 31st at the age of 103.

All of page 3 of the May 28th Chicago Tribune was dedicated to damage photos in Mattoon.

After briefly lifting near Loxa, the tornado moved into Charleston around 3:45 pm. In this area, the damage path was more in the heart of the town, in a path 1.5 miles long and 600 yards wide. Damaged or destroyed were 15 businesses, two lumberyards, 2 railways stations, the high school, county fairgrounds, power station, and gas reservoir. Over 220 homes were destroyed, and another 265 seriously damaged, with damage estimates at $1 million (in 1917 dollars). J.P. Carey of the Eastern Illinois Normal School (now Eastern Illinois University) described the parts of town with the worst damage as "more completely demolished than if a gigantic roller had passed over them, for the buildings were broken into short sticks, split into narrow pieces, and some parts carried rods and even miles eastward."

Initial media reports were between 50 and 75 people dead in Charleston. However, the actual death total was determined to be 34, with 182 people injured.

Initial media reports were between 50 and 75 people dead in Charleston. However, the actual death total was determined to be 34, with 182 people injured.

Medical services were at capacity at Montgomery Hospital, and the injured were cared for in private homes, hotels, lodgerooms, and the dormitories at the university. Doctors as far away as Terre Haute, Indiana, came to assist.

National Guardsmen from the 4th Illinois Infantry, Company A from Casey and Company D from Paris, were brought in to patrol the area against looting. A 6:00 pm curfew was established and the guardsmen were ordered to "shoot vandals on sight."

The Red Cross distributed food and clothing to the homeless. Temporary lodging was set up in the county building with 300 blankets, 150 mattresses, and 100 cots. A shipment of 200 tents from Springfield was also used for people to sleep.

The local newspaper, the Charleston Courier, was hard-hit and unable to publish until Monday, May 28th, when it issued a "Cyclone Edition" consisting of only a single 12x15 inch sheet of paper containing a list of the deceased.

The following people perished in Charleston as a result of their injuries:

|

|

Before and after images of the Big Four Railroad Depot in Charleston. Images from the Coles County Historical Society.

|

|

| Headline from the Decatur Daily Review, May 28th | "Nature's Fury and the Human Spirit", a documentary on the tornado by Cameron Craig and William Lovekamp of Eastern Illinois University (run time: 26 minutes) |

Report of Tornado Disaster, published in 1918, used rather colorful language to describe the aftermath:

| Men, women and children, buried beneath debris, were crying for assistance. The injured, groaning under the agony of intense suffering, were imploring aid. The more fortunate, dazed and mud bespattered, were groping for friends and relatives, while the bodies of the dead dotted the devastated region. |

In one home, a bedroom remained nearly untouched while the remainder of the home was destroyed. A woman was found unconscious in the bed, with her four year old child deceased at the foot. However, she had given birth during the storm, and the baby was found alive under the blankets.

|

The Journal Gazette from June 18th reported a story about Decatur resident Margaret Hayes, 76, who was visiting relatives near Mattoon at the time and suffered a broken arm in the storm:

In August, the Journal Gazette reported that the "ghost" of one of the Mattoon tornado victims, Emma Turner, continued to haunt the area near her N. 28th St. home. A relative, James Turner, related that the noise was heard two mornings in a row:

|

Mattoon Journal-Gazette, June 1 |

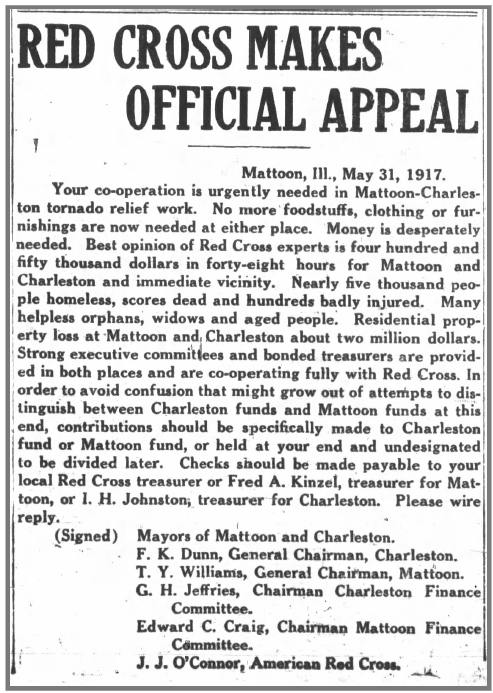

Donations for Mattoon and Charleston came in from all over the country. This included $5 from the granddaughter of town founder William Mattoon.

The force of the wind caused several notable occurrences, according to Root and Carey, as well as newspaper reports:

The March 22, 1918 issue of the Journal Gazette reported on a postcard recently found near Lagoda, Indiana, in a strawberry patch. The postcard was addressed to Lucille Bingamon, who had survived the storm with her stepfather and a sister, although her mother and two other siblings were killed. The finder, George Frantz, wrote to Lucille about the find.