The Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society (BAMS) published a study in its September 2016 edition titled, “Effectively Communicating Risk and Uncertainty to the Public.” The study was jointly funded by NOAA’s National Weather Service (NWS) and Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research (OAR) to study how residents in Easton and Lambertville, Pennsylvania perceive and respond to risk communication in NWS flood forecast products. The study’s findings reveal tools and thought processes people use to make decisions about their safety, in response to floods. The study also suggests ways NWS can adapt its flood products and messages to motivate people to take action.

Let’s review two insights from the study that improve the communication of flood risks:

1. "What Does It Mean For Me?" - Risk Must Be Personalized Before People Take Action

According to the study, “People differ in how they react to uncertainty; for some, not having a concrete example of what a risk means can make them uncertain of what the actual impacts might entail, and thereby impede their decision on whether to take action” (Carr et al., 1650).

We are in the information age where television, radio, web and social media, mobile apps, and alerts are all dependable information outlets for weather forecasts. But knowing the risks isn’t enough, because we are usually motivated to take action by concrete messages we can perceive, thereby allowing us to personalize the risk.

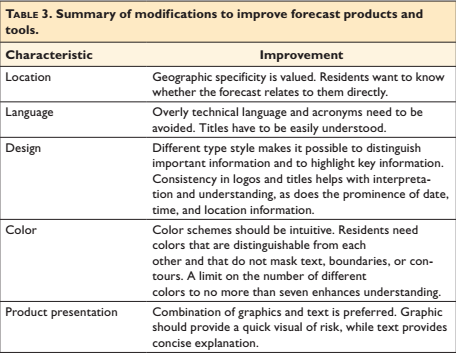

The table below summarizes input from study participants on ways NWS products and messages could be modified to show personalization of risk.

|

Of all the NWS products that were tested on participants, the NWS Hydrograph was the best for motivating action in response to flood risk because, “When they [saw] it reaching flood level, preparations [began]” (Carr et al.,1656). The Hydrograph allowed participants to see the rising water of the Delaware River, which made them feel what the risk meant for them. Once they could perceive the risk, they began to take action. Participants were also more motivated to act when Flood Watches and Warnings (non-graphic products) used a concrete word to describe flooding, such as damaging, instead of significant. One participant said, “When it says damage and flooding possible, I’m calling my friends along the river and asking if they’re paying attention” (Carr et al.,1659). This telling statement leads to the second insight. 2. Peer Influence Impacts Your Decisions More Than Information |

Source: Carr et al., 1662 Source: Carr et al., 1662 |

Where Do We Go From Here?

Too many weather-related tragedies still dominate the headlines despite cutting-edge forecast accuracy that was unimaginable a quarter century ago. This dilemma is the motivating force behind NOAA’s Weather-Ready Nation initiative, which seeks to mitigate the devastating impacts of extreme weather through the communication of actionable forecasts. Social science research, like the BAMS article featured here, plays a fundamental role in building a Weather-Ready Nation by helping NOAA understand what it takes for people to perceive their risk during extreme weather events, personalize their risk, make decisions, and take actions that keep them safe.

Reference:

Carr, R.H., Montz, B., Maxfield, K., Hoekstra, S., Semmens, K., Goldman, E. (2016). Effectively Communicating Risk and Uncertainty to the Public. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, (97), 9. 1649-1665