The first Wireless Emergency Alert (WEA) was sent on June 28, 2012, by the National Weather Service for a Flash Flood Warning near Santa Fe, New Mexico. Since then, the agency has activated 60,000 WEAs to warn the public about hazardous weather near them. WEAs are text-like messages accompanied by a series of loud tones sent to compatible cell phones by authorized government officials to alert individuals of an imminent threat to safety in their area.

With cell phone usage on the rise – 97% of Americans own a cell phone, according to Pew Research – WEAs are reaching more people than ever, helping to keep them safe during an emergency.

We connected with NWS Wireless Emergency Alert expert Mike Gerber to learn more about this powerful tool and what the future holds.

What is the biggest benefit of WEAs?

In weather emergencies, warnings can save lives because they give people the information they need to take protective action. WEA has helped to get emergency weather information to people when and where they might otherwise not receive it. Using WEA, NWS can send a warning describing the hazard along with action people should take to their mobile phone when they are in harm's way. WEA does not require people to download an app or subscribe to a service. In short, WEAs have been a game changer in helping the NWS get warnings to people quickly, if they are located near a threat.

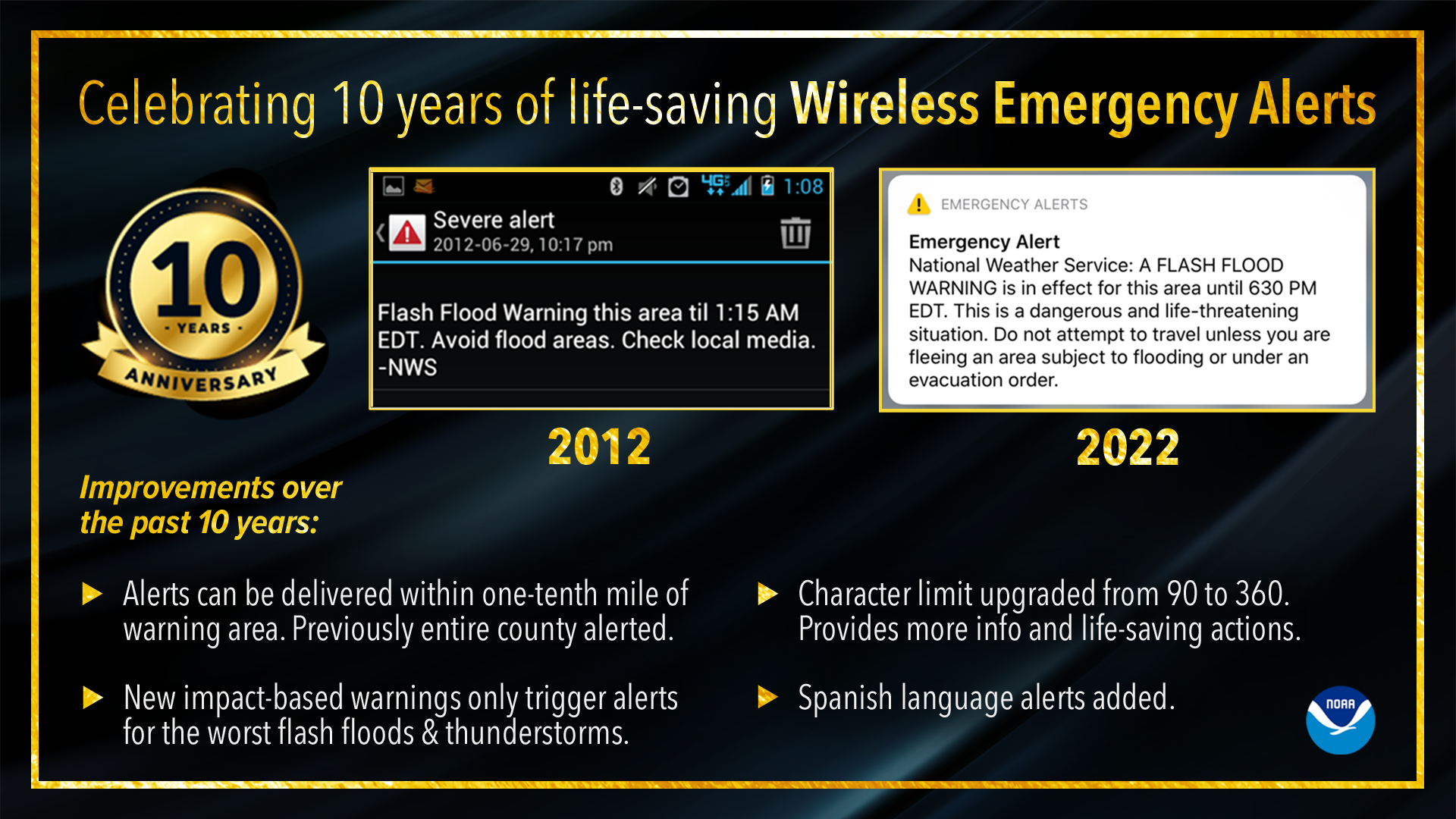

Comparison of a Wireless Emergency Alert from 2012, the first year they were activated, and one from 2022.

Over the past decade, the National Weather Service has improved WEA messages and format

to better communicate weather warnings to the public.

Can you recall an instance when you knew a WEA saved lives?

First, I want to recognize the important role played by the skilled and dedicated NWS forecasters across the country who issue the life-saving weather warnings that activate WEA.

I’ve heard dozens of stories of lives saved and tragedies avoided as a result of WEAs; two events in the first and second year really stick out in my mind. The first was during the July 26, 2012 Elmira, New York, tornado that carved a 10 mile path and damaged 2,000 structures. Public safety officials initially expected fatalities, but amazingly there weren’t even any injuries. Through conversations with survivors from the event, many said that they received a Tornado Warning on their phone from WEA, a service they didn’t even know existed. They got the warning in time and immediately took shelter.

On July 1, 2013 a Tornado Warning was issued for East Windsor, Connecticut. A local camp manager received the WEA instantly. Seeing the alert on her phone, she immediately rushed 29 children and 4 other camp counselors out of the vulnerable soccer dome they were in at the time and into an adjacent, sturdy building. Within seconds, the soccer dome was lifted by tornado’s winds and thrown high across a nearby highway. This example not only showed the power of WEAs to provide timely alerts but that when people take the message seriously and act on it, lives can be spared and serious injury can be avoided. Read about other examples.

How have WEAs changed over the years?

The NWS has helped propel or initiate a number of key improvements to how we leverage the WEA service. In terms of capability, the WEA original message limitation of 90 characters was expanded to allow 360 characters back in June 2020. This allows for even more critical information about the specific weather warning and additional sheltering guidance to instantly reach the receiver. As part of that message character limit expansion, the NWS also implemented Spanish language messages for cell phones set to Spanish. WEA geographic targeting has improved on newer cell phones, allowing these devices to more precisely alert those in the warned area and reducing false alarms to people outside the alert area.

With the goal of improving public response to weather-related warnings, the NWS has used WEAs to deliver clear information on impacts expected and the actions that should be taken by people in harm's way. When we received comments from the public about too many WEA activations for Flash Flood Warnings, we listened. We modified the threshold so that WEA is only activated for those flash floods expected to cause considerable or catastrophic damage. When a tornado or flash flooding is expected to be catastrophic, the NWS can now use emergency wording, elevating the urgency that action must be taken. And the NWS added WEA activation for Severe Thunderstorm Warnings, but only when the storm is expected to be destructive.

What will WEA messages look like in 5 to 10 years?

NWS is always looking for ways to make receiving weather and water alerts more timely, precise, and actionable. We want upgrades to be made that improve public response to NWS warnings, so that people take timely and decisive life-saving action.

We’d like WEA messages to include a map showing where the threat is relative to the alert recipient as well as any symbols that would help convey the message. We’d like to see such capabilities take social science into account, so we can be sure people understand the map, that it complements the WEA text message, and improves overall understanding of the threat without delaying action to ensure safety. We’ve already made public recommendations to the Federal Communication Commission that WEA be upgraded to include a map showing the recipient’s location relative to the alert location.

Updates during an event can help people make better decisions minute by minute. We’d like WEA to be able to provide recipients with the most up-to-date information about the specifics of the hazard especially for people who are traveling through the alert area. For example, NWS forecasters update Tornado Warnings as a tornado travels across a landscape. We’d like the updated information to be communicated to the mobile device so the WEA content remains fresh, but not reactivate all of the bells and whistles unless there is a major change that demands the recipient’s attention.

In an effort to improve access to NWS services for people and communities with limited English proficiency, we envision a future of WEA messages available in additional languages. Not only are multiple languages spoken across the United States, but consider that non-English speaking people from other countries visit the United States and are subject to the same hazards. Availability of WEA in additional languages would help ensure all communities hear and understand the hazard alert and take appropriate actions.

Accessibility of alert messages for people with disabilities is important to the NWS. We want WEA to evolve in a way that provides maximum accessibility for people with vision and hearing impairments.

We’d also like to explore the potential for an “all clear” WEA message, where the warning has either been canceled or expired and the recipient’s area is no longer under threat.

What technology and steps are involved with sending a WEA?

When NWS issues a weather warning intended to activate WEA, it is immediately sent in the Common Alerting Protocol (CAP) format to the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) Integrated Public Alert and Warning System (IPAWS). If it meets the proper thresholds, IPAWS then sends an alert to wireless carriers who then broadcast the alert via cell tower antennas that reach the alert area. Cell phones in the alert area will then receive the WEA.

Who manages the WEA system?

WEAs are the product of a successful partnership between the U.S. government and the wireless communications industry to deliver life-saving information to the public. They are distributed using FEMA’s IPAWS, which enables delivery of all-hazard alert information through as many communication pathways as possible.