Meteorological History | Satellite & Radar | Storm Impact | Storm Statistics | Personal Stories | Research & Links

Hurricane Hugo was one of the strongest hurricanes in South Carolina's history, and was at the time the most costly hurricane ever in the Atlantic Ocean. Hugo's destruction wasn't limited to just South Carolina; Hugo also devastated the Caribbean Islands of Guadeloupe, St. Croix, and Puerto Rico, and even seven hours after its final landfall still produced hurricane-force winds across the western Piedmont and foothills of North Carolina. In all, Hugo was responsible for at least 86 fatalities and caused at least $8 to $10 billion in damage [unadjusted 1989 dollars; some sources quote higher damage and fatality statistics].

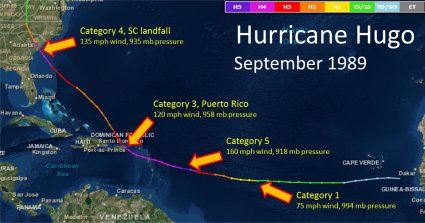

Hugo originated from a tropical wave that moved westward off the African coast September 9, 1989. By the morning of September 10th the system displayed enough organization on satellite imagery that it was classified as a tropical depression, the eleventh one of the 1989 Hurricane Season. Hugo gradually strengthened as it moved across the warm waters of the tropical Atlantic, remaining between 12 and 14 degrees north latitude. Hugo attained hurricane strength on September 14th, then turned west-northwestward early on September 15th as it quickly strengthened into a rare category five hurricane with maximum sustained winds near 160 mph and a central pressure of 918 millibars (27.11 inches Hg). The fascinating story of how Hugo nearly killed the crew of a NOAA Hurricane Hunter aircraft sent to investigate the storm is available at this link.

Hugo originated from a tropical wave that moved westward off the African coast September 9, 1989. By the morning of September 10th the system displayed enough organization on satellite imagery that it was classified as a tropical depression, the eleventh one of the 1989 Hurricane Season. Hugo gradually strengthened as it moved across the warm waters of the tropical Atlantic, remaining between 12 and 14 degrees north latitude. Hugo attained hurricane strength on September 14th, then turned west-northwestward early on September 15th as it quickly strengthened into a rare category five hurricane with maximum sustained winds near 160 mph and a central pressure of 918 millibars (27.11 inches Hg). The fascinating story of how Hugo nearly killed the crew of a NOAA Hurricane Hunter aircraft sent to investigate the storm is available at this link.

Hugo weakened to a category 4 hurricane on September 16th as it aimed at the Leeward Islands of Guadeloupe and Montserrat. Maximum sustained winds were estimated near 120 knots (140 mph) as the hurricane crossed Guadeloupe around 1 a.m. on September 17th. Hugo's eye crossed St. Croix in the U.S. Virgin Islands early in the morning of September 18th, then just six hours later struck the island of Vieques along the east coast of Puerto Rico with winds estimated near 110 knots (125 mph). An anemometer on the ship Night Cap in the harbor at Culebra measured a wind gust of 148 knots (170 mph). Hugo then slammed through Puerto Rico itself during the day of September 18th, making landfall near the town of Fajardo. The airport in San Juan registered wind gusts up to 80 knots (92 mph) with 104 knot (120 mph) gusts measured at the former Roosevelt Roads Naval Station.

Passage over the high terrain of Puerto Rico weakened Hugo significantly; the central pressure rose from 940 millibars at landfall to 966 millibars during the afternoon of September 19th and maximum sustained winds fell to 90 knots (105 mph). Hugo's eye filled with clouds on visible satellite imagery and a clear eye was not discernable again until September 20th.

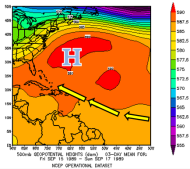

Hugo was steered across the Atlantic by the east-southeasterly flow around the southern edge of subtropical high pressure over the western Atlantic. The western periphery of this high extended to just off the Mid-Atlantic and New England coastline. As upper level low pressure developed over the eastern Gulf Coast states, a relatively narrow corridor was created for Hugo to travel along -- aimed squarely at the Carolina coast. Even given the relatively primitive computer models of the day, forecasts for Hugo's landfall consistently targeted the coast of South or North Carolina. Hugo became better organized as it crossed the warm water of the Western Atlantic Ocean between the Bahamas and South Carolina. The hurricane strengthened and a large eye appeared in satellite imagery. As Hugo crossed the Gulf Stream and approached the South Carolina coast during the evening of September 21st the storm's pressure fell to 935 millibars (27.61 inches Hg.) and maximum sustained winds increased to 120 knots (140 mph), again making the storm a category four on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. Landfall occurred at midnight September 22, 1989 near Sullivan's Island, SC.

Hugo was steered across the Atlantic by the east-southeasterly flow around the southern edge of subtropical high pressure over the western Atlantic. The western periphery of this high extended to just off the Mid-Atlantic and New England coastline. As upper level low pressure developed over the eastern Gulf Coast states, a relatively narrow corridor was created for Hugo to travel along -- aimed squarely at the Carolina coast. Even given the relatively primitive computer models of the day, forecasts for Hugo's landfall consistently targeted the coast of South or North Carolina. Hugo became better organized as it crossed the warm water of the Western Atlantic Ocean between the Bahamas and South Carolina. The hurricane strengthened and a large eye appeared in satellite imagery. As Hugo crossed the Gulf Stream and approached the South Carolina coast during the evening of September 21st the storm's pressure fell to 935 millibars (27.61 inches Hg.) and maximum sustained winds increased to 120 knots (140 mph), again making the storm a category four on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. Landfall occurred at midnight September 22, 1989 near Sullivan's Island, SC.

Wind gusts as high as 94 knots (108 mph) were measured in the city of Charleston, with 93 knots (107 mph) at Folly Beach, SC. The ship Snow Goose was anchored in the Sampit River (northern extension of Winyah Bay) near Georgetown and recorded a sustained wind of 104 knots (120 mph) on an anemometer mounted 61 feet high. Due to Hugo's rapid forward speed and relatively large size, hurricane force winds were able to reach inland areas that almost never see such severe conditions. At 2 a.m. the storm was located approximately halfway between Charleston and Sumter, SC, with maximum sustained winds estimated around 85 knots (100 mph). Shaw Air Force Base in Sumter recorded a wind gust of 95 knots (109 mph) as the eye of Hugo brushed by just to the south. By 5 a.m. Hugo's center was crossing Interstate 77 between Columbia and Charlotte with wind gusts at the Charlotte International Airport measured at 55 knots (63 mph). Winds would eventually gust to an unbelievable 100 mph in Charlotte! Hugo's winds across western North Carolina caused tremendous destruction to a region that virtually never sees such impacts from a tropical system.

Wind gusts as high as 94 knots (108 mph) were measured in the city of Charleston, with 93 knots (107 mph) at Folly Beach, SC. The ship Snow Goose was anchored in the Sampit River (northern extension of Winyah Bay) near Georgetown and recorded a sustained wind of 104 knots (120 mph) on an anemometer mounted 61 feet high. Due to Hugo's rapid forward speed and relatively large size, hurricane force winds were able to reach inland areas that almost never see such severe conditions. At 2 a.m. the storm was located approximately halfway between Charleston and Sumter, SC, with maximum sustained winds estimated around 85 knots (100 mph). Shaw Air Force Base in Sumter recorded a wind gust of 95 knots (109 mph) as the eye of Hugo brushed by just to the south. By 5 a.m. Hugo's center was crossing Interstate 77 between Columbia and Charlotte with wind gusts at the Charlotte International Airport measured at 55 knots (63 mph). Winds would eventually gust to an unbelievable 100 mph in Charlotte! Hugo's winds across western North Carolina caused tremendous destruction to a region that virtually never sees such impacts from a tropical system.

By daybreak on September 22nd the storm had been inland for many hours and the eye was no longer discernible in satellite and radar imagery. Hurricanes need the continuous extraction of heat energy from a warm ocean surface to maintain their low pressure and strong winds. Hugo crossed Interstate 40 between Hickory and Morganton and was downgraded to a tropical storm. The weakening storm then turned northward and moved through the mountainous terrain of Virginia and West Virginia, still producing wind gusts of 40 to 55 mph east of the storm's center.

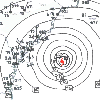

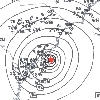

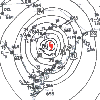

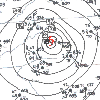

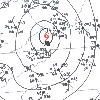

Surface Maps

The following series of three-hourly surface maps were hand-analyzed in September 2014 using archived surface observations from NWS and FAA airports and buoys operated by NOAA/NDBC.

Sep 22, 1989 0000 UTC/8 PM EDT |

Sep 22, 1989 0300 UTC/11 PM EDT |

Sep 22, 1989 0600 UTC/2 AM EDT |

Sep 22, 1989 1200 UTC/8 AM EDT Sep 22, 1989 1200 UTC/8 AM EDT |

Sep 22, 1989 1500 UTC/11 AM EDT Sep 22, 1989 1500 UTC/11 AM EDT |

Daily visible and infrared satellite images from NOAA's polar orbiting satellites are presented here. Visible imagery is AVHRR Channel 2 (0.75 to 1.1 micron) and infrared imagery is AVHRR Channel 4. (10.5 to 12.5 microns)

When Hurricane Hugo occurred in 1989 the NWS used analog WSR-57 and WSR-74 radars. Here are some radar views of Hugo as it struck the coast.

|

WSR-57 radar image from Charleston at 12:19 AM EDT (0419 UTC) on Sep 22, 1989. Charleston was in Hugo's eye at this time. |

Credit NOAA/AOML/Hurricane Research Division |

WSR-74 radar image from Columbia at 12:30 AM EDT (0430 UTC) on Sep 22, 1989. Image taken from a video provided by WPDE TV. |

|

Four-panel Charleston radar images from 10:01 pm, 11:00 pm, 12:08 am, and 1:01 am EDT. |

One-minute imagery from Charleston's WSR-57 radar as Hugo made landfall. |

Charleston radar from 3:02 am on September 22, 1989. Hugo was still a powerful hurricane centered midway between Manning and Columbia, SC. |

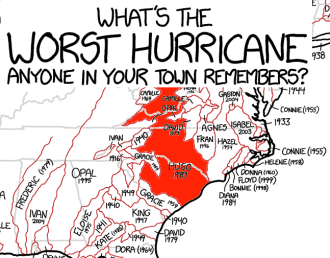

From a 20 foot storm tide at the coast to hurricane force wind gusts observed 200 miles inland, Hugo dealt a severe impact to both South and North Carolina. It is no exaggeration to say Hugo is the worst natural disaster in memory for most residents of South Carolina and western North Carolina. This was visualized exceptionally well in the xkcd webcomic shown to the right. (credit: https://xkcd.com/1407)

From a 20 foot storm tide at the coast to hurricane force wind gusts observed 200 miles inland, Hugo dealt a severe impact to both South and North Carolina. It is no exaggeration to say Hugo is the worst natural disaster in memory for most residents of South Carolina and western North Carolina. This was visualized exceptionally well in the xkcd webcomic shown to the right. (credit: https://xkcd.com/1407)

Storm impacts below are grouped by location. Information was taken from NOAA/NWS/NHC summaries, various newspaper reports, and the commercial publication Hurricane Hugo Storm of the Century.

Mt. Pleasant and Awendaw, SC: Ground zero for Hugo's landfall on the South Carolina coast, Mt. Pleasant suffered heavy wind damage to structures and trees. Roads were impassible due to the volume of debris. Multiple fishing boats were sunk in Shem Creek. Bulls Bay just north of Mt. Pleasant was the site of the highest presumed storm tide, up to 20 feet based on debris marks noted after the storm. In Awendaw the storm tide reached 19.4 feet, and the U.S. 17 bridge across Awendaw Creek was destroyed.

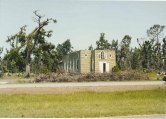

McClellanville, SC: Still a relatively sleepy fishing community in the 1980s, McClellanville was severely impacted by Hugo's wind and storm surge. Many homes and businesses were destroyed, and the storm surge carried boats from the rivers and marshes across highways and left them haphazardly strewn around. Lincoln High School in McClellanville was selected as an emergency evacuation shelter due to maps indicating an elevation of 20 feet above sea level. The actual elevation was only 10 feet above sea level, meaning Hugo's 16 foot storm surge swept 6 feet of seawater into the school gynmasium full of evacuees. A fascinating eyewitness account of this true life survival story by paramedic George Metts is available here.

The National Weather Service in Wilmington came into possession of a series of photos taken in McClellanville nine months after Hugo, shown below:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Charleston, SC: Water crashed over the historic seawall in downtown Charleston and flooded the first floor of homes. Up to 80 percent of roofs in the city of Charleston were damaged. Over 100 buildings suffered heavy structural damage or completely collapsed. A million-dollar crane at the Port of Charleston was destroyed. Amazingly only one death in Charleston was directly attributable to Hugo. An October 1990 NOAA report titled Hurricane Hugo: Learning from South Carolina suggests much of the extreme roof damage observed along the South Carolina coast was attributable to "poor roof covering installation practices, poor roof maintenance, [and] aged roofing materials..." The report mentions in the city of Charleston a high percentage of the residential, commerical and governmental buildings used sheet metal as a roofing material which failed as wind peeled it back from the roof edge.

Francis Marion National Forest, SC: Approximately three-quarters of the trees in this 250,000 acre national forest were blown down, many sheared off at a height of 10 to 25 feet above ground. A USDA Forest Service report issued on October 5, 1989 estimated 700 to 1000 million board feet of timber was lost, but up to 250 million board feet was hoped to be salvaged over the coming years. The endangered Red-cockaded Woodpeckers lost much of their habitat in the Francis Marion National Forest.

Folly Beach, SC: Various news reports claimed anywhere from 30 to 80 percent of homes on the island were heavily damaged or uninhabitable. Pavement was scoured off the roads by the storm surge. The famous Atlantic House restaurant was destroyed. A storm surge of 12 feet plus high waves destroyed virtually all single family homes on the ocean front. The second and third rows of homes experienced lesser damage.

Isle of Palms and Sullivan's Island, SC: An eleven foot storm surge destroyed the Isle of Palms fishing pier and many of the beachfront homes. The Wild Dunes golf course was damaged by erosion, and a large section of the Ben Sawyer Bridge over to Sullivan's Island was damaged. Newspaper reports indicate every building on Isle of Palms and neighboring Sullivan's Island suffered at least some damage from Hugo. Mayor Carmen Bunch and SC Governor Carroll Campbell placed the island under martial law. Sullivan's Island experienced water 13 feet above mean sea level, and many of the older homes east of Marshall Avenue were destroyed.

Isle of Palms and Sullivan's Island, SC: An eleven foot storm surge destroyed the Isle of Palms fishing pier and many of the beachfront homes. The Wild Dunes golf course was damaged by erosion, and a large section of the Ben Sawyer Bridge over to Sullivan's Island was damaged. Newspaper reports indicate every building on Isle of Palms and neighboring Sullivan's Island suffered at least some damage from Hugo. Mayor Carmen Bunch and SC Governor Carroll Campbell placed the island under martial law. Sullivan's Island experienced water 13 feet above mean sea level, and many of the older homes east of Marshall Avenue were destroyed.

Georgetown, SC: Storm surge flooding occurred in the historic downtown area. A sailboat that had been anchored in the Sampit River ended up stranded next to the Georgetown Rice Museum. Both the Georgetown Landing and Belle Isle marinas were destroyed.

Pawley's Island, SC: Hugo's surge cut the island in two, carving out a new inlet described in two different news sources as 20 feet or 100 feet wide. At least 14 homes were destroyed, and three homes were carried off by surging water and dropped in the tidal creek behind the island.

Murrells Inlet, SC: A local marina was completely destroyed and a large diesel fuel spill occurred.

Garden City, SC: Although the worst of Hugo's wind remained just south of Garden City a tremendous storm surge wiped out up to 90 percent of homes and undermined beachfront hotels and condos. In newspaper reports published on September 23, 1989, Horry County administrator M. L. Love said "Garden City for all practical purposes is gone." The city's pier was destroyed, and roads three blocks inland were covered with sand. The surge was estimated at 13 feet above sea level, with evidence of damage from seawater flooding as far as 1,500 feet inland.

Garden City, SC: Although the worst of Hugo's wind remained just south of Garden City a tremendous storm surge wiped out up to 90 percent of homes and undermined beachfront hotels and condos. In newspaper reports published on September 23, 1989, Horry County administrator M. L. Love said "Garden City for all practical purposes is gone." The city's pier was destroyed, and roads three blocks inland were covered with sand. The surge was estimated at 13 feet above sea level, with evidence of damage from seawater flooding as far as 1,500 feet inland.

Surfside Beach, SC: On Ocean Boulevard sand and mud was 10 inches deep after the storm with tree and building debris littering the streets. The Surfside Fishing pier was destroyed. Surge height was estimated at 13 feet above sea level.

Myrtle Beach, SC: Hotels and homes on the beachfront were heavily damaged and the bulk of the protective sand dunes were washed away. Springmaid Pier was reduced to only 150 feet in length with two other piers in Myrtle Beach destroyed by the combination of storm surge and large crashing waves. Newspaper reports said Ocean Boulevard was covered by sand and several feet of water in the North Myrtle Beach area. About 150 wooden beach access walkways were destroyed.

Sunset Beach, NC: Surprisingly little damage occurred to this westernmost beach town in Brunswick County. In the Wilmington Star-News, town mayor Mason Barber said, "We have just been blessed by nature," referring to the extremely wide area of protective dunes that separates the beach from the first row of beach homes.

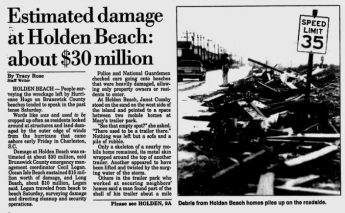

Holden Beach and Yaupon Beach, NC: At least 25 beachfront homes were damaged, and in some places 50 feet of beach was lost according to the Wilmington Star-News. Dunes previously seven to eight feet tall were simply gone after Hugo. The end of Holden Beach fishing pier was destroyed, and the Yaupon Pier was destroyed.

Holden Beach and Yaupon Beach, NC: At least 25 beachfront homes were damaged, and in some places 50 feet of beach was lost according to the Wilmington Star-News. Dunes previously seven to eight feet tall were simply gone after Hugo. The end of Holden Beach fishing pier was destroyed, and the Yaupon Pier was destroyed.

Long Beach, NC: A 200-foot section of the 800-foot long Long Beach Pier collapsed around 1 a.m. on September 22nd. The pier had recently been renovated and had been open only for five weeks before Hugo. Mayor Johnny Vereen was quoted in the Wilmington Star-News saying "We have lost 60 percent of our dune area. We have absolutely no protection."

Carolina Beach, NC: A 50 foot section in the middle of the town fishing pier was destroyed by large waves. Sand was washed onto roads at the north end of Carolina Beach.

Surf City, NC: Barnacle Bill's pier lost a 15 foot section due to high waves, and the Surf City Pier had damage to the end of its structure.

Berkeley and Dorchester counties, SC: Eight fatalities attributible to Hugo occurred in Berkeley county with a tremendous number of homes destroyed and 17,000 residents homeless after the storm. Over 70 percent of trees in the county were knocked down. Neighboring Dorchester county also suffered damage to a large number of homes, businesses and churches.

Orangeburg and Clarendon counties, SC: Large scale damage occurred to agricultural interests. Particularly hard hit were peaches, soybeans, cotton, pecans, and pine plantation forests. In Clarendon county a total of 28,000 residents were homeless after Hugo with damage reported to 70 percent of homes.

Sumter County, SC: One fatality occurred in a mobile home, with nearly a thousand homes damaged and over 200 destroyed. Tremendous damage to trees was observed.

Florence county, SC: Roofs were destroyed in downtown Florence, with damage reported to hotels and apartment buildings around the county. A very large number of trees were knocked down.

Columbia and Lexington, SC: Hurricane-force winds damaged many buildings and knocked trees down throughout the area.

Lee and Kershaw counties, SC: High winds broke windows and downed many trees.

York and Chesterfield counties, SC: Over 1,500 homes were damaged or destroyed in Chesterfield county along with heavy losses to the turkey industry. One fatality was reported in York county. Widespread damage occurred to local peach orchards, plus cotton, sorghum and soybean crops. Naturalist Bill Hilton in York County recorded his Hurricane Hugo experience on the Hilton Pond website.

Charlotte, NC: This city was forever changed by Hugo which was still packing hurricane-force wind gusts nearly 200 miles from the ocean. Countless trees crashed into homes and fell across power lines, creating widespread and long-lasting power outages. Newspaper reports indicated 85 percent of homes and businesses in Charlotte were without power after the storm. Downtown skyscrapers in Charlotte had large windows blown out by winds, raining debris into the streets below. WSOC-TV's 400-foot tall antenna tower was blown down onto the station itself. Hugo was responsible for three fatalities in the Charlotte area.

North Carolina Western Piedmont and Foothills: Hugo finally weakened below hurricane strength as it accelerated northward between Hickory and Morganton during the morning of September 22, 1989. Wind gusts reached hurricane-force and blew down millions of trees from Gastonia and Lincolnton through Hickory and the remainder of the North Carolina foothills. One apple grower in Wilkes County lost 4000 trees to high winds. Widespread power outages lasted weeks in some remote locations. Hugo's powerful wind was an unique event in weather history for this portion of inland North Carolina.

Ecological Impacts

Besides direct damage to human structures, power, and transportation networks, Hugo had an impact on the natural world as well. A paper published in 1992 titled Disturbance Effects of Hurricane Hugo on a Pristine Coastal Landscape: North Inlet, South Carolina, USA discussed how ecosystems were impacted by Hugo's saltwater storm surge that moved a great distance inland across the low terrain between the ocean and Winyah Bay. Hugo's unprecedented winds across such large portions of the interior coastal plain and Piedmont region damaged 4.5 million acres of forestland in South Carolina alone. The U.S. Forest Service produced a research paper titled Hurricane Hugo Effects on South Carolina's Forest Resource that detailed the effects observed.

Another interesting and well-documented impact hurricanes have on the natural world concerns seabirds that become trapped within the eye of a storm and are forced to move along with it. Hurricane Hugo deposited a large number of exotic birds at lakes in Western North Carolina as the eye disintegrated.

Another interesting and well-documented impact hurricanes have on the natural world concerns seabirds that become trapped within the eye of a storm and are forced to move along with it. Hurricane Hugo deposited a large number of exotic birds at lakes in Western North Carolina as the eye disintegrated.

According a publication by the Carolina Bird Club at least 25 species of birds were carried inland by Hurricane Hugo, well away from the oceanic locations they typically inhabit. Particularly noteworthy were reports of 27 Black Skimmers, six Least Terns, a Bridled Tern and a White-tailed Tropicbird near Shelby, North Carolina, approximately 200 miles inland. Lake Norman north of Charlotte also accumulated some rare species including three Brown Noddys.

| Lowest Pressure | Highest wind (kts) | Highest Wind (mph) | Storm Rainfall |

Storm tide (ft.) | ||||

| millibars | in. Hg | 1-min avg | gust | 1-min avg | gust | |||

| South Carolina… | ||||||||

| Bulls Bay | 20 | |||||||

| Awendaw | 19.4 | |||||||

| Folly Beach | 940 | 27.76 | 74 | 93 | 85 | 107 | 10-12 | |

| Mt. Pleasant | 933 | 27.55 | 71 | 83 | 82 | 95 | 8.10 | |

| Charleston Air Force Base | 943.2 | 27.85 | ||||||

| Charleston (Custom House) | 76 | 94 | 87 | 108 | 6.37 | 8-9 | ||

| Charleston NWS office | 942.1* | 27.82* | 68 | 85 | 78 | 98 | 5.90 | |

| Beaufort | 984 | 29.06 | 27 | 44 | 31 | 51 | 5.94 | |

| Georgetown | 69 | 79 | 3.74 | |||||

| Sampit River | 984.5 | 29.07 | 104 | 120 | ||||

| Myrtle Beach | 993.5 | 29.34 | 45 | 66 | 52 | 76 | 2.30 | 13 |

| Florence | 989.1 | 29.21 | 39 | 54 | 45 | 62 | ||

| Shaw Air Force Base | 959.6 | 28.34 | 58 | 95 | 67 | 109 | ||

| Summerville | 5.98 | |||||||

| Columbia | 46 | 61 | 53 | 70 | ||||

| North Carolina… | ||||||||

| Holden Beach | 51 | 59 | 6-10 | |||||

| Cape Fear River | 61 | 70 | ||||||

| Carolina Beach | 3 | |||||||

| Wilmington | 1004.5 | 29.66 | 26 | 46 | 30 | 53 | 0.79 | |

| Hatteras | 1013.1 | 29.92 | 23 | 30 | 26 | 35 | 0.60 | 4 |

| Raleigh | 1004.6 | 29.67 | 25 | 40 | 29 | 46 | 0.45 | |

| Charlotte | 978.0 | 28.88 | 60 | 86 | 69 | 99 | 3.16 | |

| Lake Norman | 79** | 93** | ||||||

| Hickory | 980.5 | 28.95 | 30 | 70 | 35 | 81 | ||

| Greensboro | 998.1 | 29.47 | 37 | 47 | 43 | 54 | 1.43 | |

| Asheville | 989.9 | 29.23 | 20 | 32 | 23 | 37 | 1.93 | |

| Boone | 6.91 | |||||||

* The NWS ER Technical Attachment Hurricane Hugo in the Charleston Area by John F. Townsend lists the minimum pressure for the NWS office in Charleston as 943.2 mb or 27.85 inches

** personal communication with Seburn Crocker of Mooresville, NC, September 2014. Anemometer located near W. Catawba Avenue about 1.5 miles west of Cornelius.

Hurricane Hugo's position (latitude, longitude), maximum sustained wind speeds, and sea level pressure as reported every six hours by the National Hurricane Center.

| Date | Time UTC | Latitude | Longitude | Wind (mph) | Wind (kts) | Pressure (mb) | Pressure (in.) |

| 9/10/1989 | 1200 | 13.2 | 20.0 | 30 | 25 | 1010 | 29.83 |

| 9/10/1989 | 1800 | 13.3 | 21.8 | 30 | 25 | 1010 | 29.83 |

| 9/11/1989 | 0000 | 13.2 | 23.7 | 35 | 30 | 1009 | 29.80 |

| 9/11/1989 | 0600 | 13.0 | 25.5 | 35 | 30 | 1007 | 29.74 |

| 9/11/1989 | 1200 | 12.8 | 27.3 | 35 | 30 | 1005 | 29.68 |

| 9/11/1989 | 1800 | 12.5 | 29.2 | 40 | 35 | 1003 | 29.62 |

| 9/12/1989 | 0000 | 12.5 | 31.0 | 45 | 40 | 1002 | 29.59 |

| 9/12/1989 | 0600 | 12.5 | 32.9 | 50 | 45 | 1000 | 29.53 |

| 9/12/1989 | 1200 | 12.5 | 34.8 | 50 | 45 | 998 | 29.47 |

| 9/12/1989 | 1800 | 12.6 | 36.7 | 60 | 50 | 996 | 29.41 |

| 9/13/1989 | 0000 | 12.6 | 38.2 | 65 | 55 | 994 | 29.35 |

| 9/13/1989 | 0600 | 12.7 | 40.0 | 65 | 55 | 992 | 29.29 |

| 9/13/1989 | 1200 | 12.8 | 41.8 | 70 | 60 | 990 | 29.23 |

| 9/13/1989 | 1800 | 12.8 | 43.5 | 75 | 65 | 987 | 29.15 |

| 9/14/1989 | 0000 | 12.9 | 44.9 | 80 | 70 | 984 | 29.06 |

| 9/14/1989 | 0600 | 13.0 | 46.3 | 90 | 75 | 980 | 28.94 |

| 9/14/1989 | 1200 | 13.2 | 47.8 | 100 | 85 | 975 | 28.79 |

| 9/14/1989 | 1800 | 13.6 | 49.1 | 105 | 90 | 970 | 28.64 |

| 9/15/1989 | 0000 | 13.8 | 50.5 | 115 | 100 | 962 | 28.41 |

| 9/15/1989 | 0600 | 14.0 | 51.9 | 125 | 105 | 957 | 28.26 |

| 9/15/1989 | 1200 | 14.2 | 53.3 | 145 | 125 | 940 | 27.76 |

| 9/15/1989 | 1800 | 14.6 | 54.6 | 160 | 135 | 918 | 27.11 |

| 9/16/1989 | 0000 | 14.8 | 56.1 | 155 | 130 | 923 | 27.26 |

| 9/16/1989 | 0600 | 15.1 | 57.3 | 150 | 125 | 927 | 27.37 |

| 9/16/1989 | 1200 | 15.4 | 58.4 | 140 | 120 | 940 | 27.76 |

| 9/16/1989 | 1800 | 15.8 | 59.4 | 140 | 120 | 941 | 27.79 |

| 9/17/1989 | 0000 | 16.1 | 60.4 | 140 | 120 | 941 | 27.79 |

| 9/17/1989 | 0600 | 16.4 | 61.5 | 140 | 120 | 943 | 27.85 |

| 9/17/1989 | 1200 | 16.6 | 62.5 | 145 | 125 | 949 | 28.02 |

| 9/17/1989 | 1800 | 16.9 | 63.5 | 145 | 125 | 945 | 27.91 |

| 9/18/1989 | 0000 | 17.2 | 64.1 | 150 | 130 | 934 | 27.58 |

| 9/18/1989 | 0600 | 17.7 | 64.8 | 140 | 120 | 940 | 27.76 |

| 9/18/1989 | 1200 | 18.2 | 65.5 | 125 | 105 | 945 | 27.91 |

| 9/18/1989 | 1800 | 19.1 | 66.4 | 120 | 100 | 958 | 28.29 |

| 9/19/1989 | 0000 | 19.7 | 66.8 | 115 | 95 | 959 | 28.32 |

| 9/19/1989 | 0600 | 20.7 | 67.3 | 105 | 90 | 962 | 28.41 |

| 9/19/1989 | 1200 | 21.6 | 68.0 | 105 | 90 | 964 | 28.47 |

| 9/19/1989 | 1800 | 22.6 | 68.6 | 105 | 90 | 966 | 28.53 |

| 9/20/1989 | 0000 | 23.5 | 69.3 | 105 | 90 | 957 | 28.26 |

| 9/20/1989 | 0600 | 24.4 | 70.1 | 105 | 90 | 957 | 28.26 |

| 9/20/1989 | 1200 | 25.2 | 71.0 | 110 | 95 | 958 | 28.29 |

| 9/20/1989 | 1800 | 26.3 | 72.2 | 110 | 95 | 953 | 28.14 |

| 9/21/1989 | 0000 | 27.2 | 73.4 | 115 | 100 | 950 | 28.05 |

| 9/21/1989 | 0600 | 28.0 | 74.9 | 115 | 100 | 950 | 28.05 |

| 9/21/1989 | 1200 | 29.0 | 76.1 | 125 | 105 | 948 | 27.99 |

| 9/21/1989 | 1800 | 30.2 | 77.5 | 140 | 120 | 944 | 27.88 |

| 9/22/1989 | 0000 | 31.7 | 78.8 | 140 | 120 | 935 | 27.61 |

| 9/22/1989 | 0600 | 33.5 | 80.3 | 100 | 85 | 952 | 28.11 |

| 9/22/1989 | 1200 | 35.9 | 81.7 | 65 | 55 | 975 | 28.79 |

| 9/22/1989 | 1800 | 38.5 | 81.8 | 45 | 40 | 987 | 29.15 |

| 9/23/1989 | 0000 | 42.2 | 80.2 | 40 | 35 | 988 | 29.18 |

| 9/23/1989 | 0600 | 46.0 | 74.5 | 45 | 40 | 990 | 29.23 |

| 9/23/1989 | 1200 | 49.0 | 69.0 | 45 | 40 | 992 | 29.29 |

| 9/23/1989 | 1800 | 51.0 | 65.0 | 45 | 40 | 993 | 29.32 |

| 9/24/1989 | 0000 | 52.0 | 62.0 | 45 | 40 | 994 | 29.35 |

| 9/24/1989 | 0600 | 52.5 | 60.5 | 45 | 40 | 993 | 29.32 |

| 9/24/1989 | 1200 | 53.0 | 59.5 | 45 | 40 | 991 | 29.26 |

| 9/24/1989 | 1800 | 53.5 | 58.5 | 45 | 40 | 989 | 29.21 |

| 9/25/1989 | 0000 | 54.0 | 57.0 | 45 | 40 | 983 | 29.03 |

| 9/25/1989 | 0600 | 56.0 | 52.0 | 45 | 40 | 979 | 28.91 |

| 9/25/1989 | 1200 | 58.0 | 46.0 | 45 | 40 | 974 | 28.76 |

Rainfall totals were surprisingly low for such a large and powerful hurricane. Hugo's rapid forward movement, nearly 35 mph as it turned north-northwestward between Columbia and Charlotte, was likely responsible for these low totals. Over 10 inches of rain was recorded at Edisto Island, SC with rather large totals southward through coastal Georgia. A secondary maximum of heavy rainfall occurred in the North Carolina and Virginia mountains as tropical air was pushed up and over the ridges. Across Southeastern North Carolina rainfall amounts ranged from around half an inch eight miles south of Wilmington to 1.30 inches near the Ocean Isle Bridge in Brunswick County, NC.

Rainfall totals were surprisingly low for such a large and powerful hurricane. Hugo's rapid forward movement, nearly 35 mph as it turned north-northwestward between Columbia and Charlotte, was likely responsible for these low totals. Over 10 inches of rain was recorded at Edisto Island, SC with rather large totals southward through coastal Georgia. A secondary maximum of heavy rainfall occurred in the North Carolina and Virginia mountains as tropical air was pushed up and over the ridges. Across Southeastern North Carolina rainfall amounts ranged from around half an inch eight miles south of Wilmington to 1.30 inches near the Ocean Isle Bridge in Brunswick County, NC.

Hugo left a permanent impact on the people of the Carolinas. Here are stories from several Carolinians who have strong, lasting memories from Hurricane Hugo.

Meteorologist Eric Thomas, WBTV Channel 3, Charlotte

As a Pittsburgh native and Penn State graduate in Meteorology, Tropical Weather was not my top priority since I never had a personal encounter or experience with those kinds of storms growing up. But like everyone else, I did see the coverage of these monster storms on the national news, and that was more than enough to stoke my interest. In fact, in pursuing my degree at Penn State, I fell one credit short and had to take my final course by correspondence. The course? Tropical Meteorology. Diploma earned.

As a Pittsburgh native and Penn State graduate in Meteorology, Tropical Weather was not my top priority since I never had a personal encounter or experience with those kinds of storms growing up. But like everyone else, I did see the coverage of these monster storms on the national news, and that was more than enough to stoke my interest. In fact, in pursuing my degree at Penn State, I fell one credit short and had to take my final course by correspondence. The course? Tropical Meteorology. Diploma earned.

My first job was just west of Pittsburgh at WTOV in Steubenville, OH. Not exactly a tropical hotbed in that part of the country either, but I worked there only six months. Then I landed my second television job in north Louisiana, at KNOE in Monroe between 1984 and 1988. By the end of my first year we had dealt with Danny (Category 2) and Elena (Category 3) which made landfall on the Gulf Coast and passed directly over us. These two storms were only three weeks apart. Monroe is a solid 200 miles inland, but both these storms produced very rough weather across our area and thus, I thought I had learned what to expect from dying hurricanes which move that far inland.

After four years in Louisiana, I returned to the east coast in the fall of 1988 to start my tenure at WBTV. It didn’t take long for me to get initiated to Carolina weather. By November I was flying over and reporting on the damage of an F4 tornado the wreaked havoc in our state capitol of Raleigh. But that was just the beginning. Next up was 1989, and a new storm was developing in the Atlantic Basin. It would be given the name: Hugo.

This may surprise some, but I was the first degreed meteorologist to work on a newscast in the Charlotte television market. I had been here only one year and I felt a lot of pressure to live up to the expectations people had of this new breed of scientist now appearing. The problem was, we still had no meteorological equipment in the station that would help me analyze weather in any meaningful way. We were in the process of procuring it, but not in time for this fateful storm. The extent of my weather charts amounted to one 8x10 sheet of paper faxed to us from Accu-Weather showing a simplified surface map of the United States and the positions of the cold fronts and warm fronts. We did have a weather ticker too, so at least I was able to read the discussions and bulletins being issued by the National Weather Service and National Hurricane Center. So from that standpoint I was able to talk somewhat intelligently about the impending weather. We also had an early generation of a local Doppler radar, but that doesn’t help when dealing with tracking tropical cyclones.

As Hugo moved out of the Caribbean and Puerto Rico as a menacing Category 4 hurricane, Accu-Weather did a good job of keeping me apprised of its movement and regularly sent us their own forecast thoughts. Hugo was not a tricky storm to forecast. The steering currents aloft made it clear Hugo would be driven directly into South Carolina. But something even more ominous was becoming clear. It was likely going to accelerate as it made landfall and plow right up I-26 toward Charlotte. The alert went out and we set up hour-long weather specials at WBTV in advance of the storm to warn people of the unusual circumstances. We even had experts on the programs such as Bob Sheets, the Director of the National Hurricane Center. We were all warning people to tie down their patio furniture and prepare for damaging winds and power outages. But none of us suggested what would ultimately happen.

Sure enough, Hugo came ashore on midnight 22 September 1989 just north of Charleston, SC and accelerated inland at 35 mph. With only 175 miles of ground to cover, that meant the center of Hugo would make it to Charlotte in just five hours. That’s not enough time to spin down a Category 4 hurricane. And keep in mind strong winds arrived here well ahead of the center. Mike McKay was our evening news weathercaster while I was the morning meteorologist. Based on the timing of the storm, there was no compelling reason to change our shifts, so Mike worked the 11pm news and handed it off to me.

Figuring the worst of the storm would hit around 5am, I decided to head in around 2am. The wind was already whipping outside as I woke up and got ready. As I prepared to leave I took one last look at my sleeping wife, who was five months pregnant with our first child. I must admit, that gave me pause. It went against my instincts to leave my pregnant wife home alone under these circumstances. But then again, I had lived through these storms in Louisiana and knew nothing terribly serious would happen… or so I thought.

As I drove to work and saw the trees bending in the wind, I really felt vulnerable and thought I had waited too long to get to work. I felt a sense of danger. Then I noticed all the lightning around, but no bolts. Oh wait… that wasn’t lightning… it was transformers blowing up! Concern turned into fear and all I could think about was getting to work in one piece. Thankfully I made it. But here is where the story takes a turn. If you are expecting me to tell you about the next five hours of hurricane coverage, you’ll be disappointed. Our TV station lost power and we had no generator. Game over. We had nowhere to turn. We ended up firing up a small portable generator which from my understanding may have produced a signal several miles in diameter, but it didn’t matter. Nobody in that small coverage area had power either.

So I had plenty of time to actually experience the storm. I remember standing in the mouth of our large garage at the peak of the storm looking across the parking lot at the horizontal rain and large chunks of debris flying through the air. I had an impulse to run out into the driving rain and experience it just like the reporters on the coast, but when I saw the debris hurling around, I realized it was truly dangerous. I guess when you’re on the beach covering these storms, there isn’t much debris coming off the ocean. That scene was seared into my memory, but it would pale in comparison to my next encounter.

When the sun came up, someone came running down the hall yelling, ‘Oh My God, come down to the radio station and look out the window!!’ We have very few windows on the news operations level of our building. The radio station looks over a large grass-covered hill filled with trees. It was a beautiful park setting. I gasped as I looked out the window. It appeared at least 80% of what must have been 100 trees were mowed down like Godzilla had just terrorized our end of town. Then the reports started coming in – trees down everywhere. Roads blocked. Power out. The city was paralyzed. I couldn’t imagine what the coastal cities must have looked like if we were in this kind of shape. It was beyond anything I could have imagined. My prior experience had not prepared me for this.

By 11:00am, the sun was out, we were still off the air, and there was little more I could do. With no cell phones, and a certainty the power was out at my home, it was time to get there and check on my wife. As I rolled down the hill just a thousand feet from my station, I came to the first intersection. The stoplight wasn’t working or course but we had someone directing traffic. I looked more closely. It was a National Guardsman with an M-16 machine gun. I swallowed hard when I saw that. I had never seen an automatic weapon before. So this is what they meant when storm survivors said it looked like a war zone. I guess I’m no different than anyone else. I too thought this stuff only happened to ‘other’ people. It took me a long time to get home as I encountered numerous delays with trees, power lines, signs and debris in the road along with the detours. But somehow I made it.

Vickie was fine, we lived in a new subdivision - you know, the kind where they mow down all the trees before building the first house? Well I suppose that was our saving grace because our house was not damaged, and our power was back on within just a few days. Some residents didn’t get power back for three weeks! While I was still amped up, I had Vickie grab the camcorder and we went out and taped a news-reporter-like story on the damage around our neighborhood. Yes I still have it, and squirm every time I see myself standing there in my short-short tennis shorts and tube socks. What was I thinking? Sorry, this is a written account of my experience, video not included.

My last memory is probably of the endless sounds of chainsaws you could hear for days and days after the storm. And with the power outage spanning that length of time, everyone in the neighborhood was emptying their refrigerators and feverishly cooking anything that would otherwise spoil. The outdoor grills were going strong and I must say, it created a real sense of community among our neighbors as we were all coming together to share food and check on each other’s needs.

In closing, while I do carry a few fond memories from that event, make no mistake, I hope I never see anything like that again in my lifetime. It certainly gave me a whole new appreciation and understanding of what hurricanes are capable of, and not just along the coast. And I believe it made me a better meteorologist with a keener understanding of how to inform and, if necessary, warn people of the dangers from tropical weather even in this normally protected region.

Meteorologist Robb Ellis, WISH TV, Indianapolis, IN

Every good meteorologist will tell you there was one weather event that impacted their childhood so greatly, that they decided to spend their life in pursuit of understanding the weather. For me, that event was Hurricane Hugo in 1989.

Every good meteorologist will tell you there was one weather event that impacted their childhood so greatly, that they decided to spend their life in pursuit of understanding the weather. For me, that event was Hurricane Hugo in 1989.

At the time I was just a kid, living in the suburbs of Columbia, South Carolina. I had no idea what a hurricane was, and being a kid, I didn't spend much time watching the news. I didn't know a storm was on the way.

My oldest sister had already moved away to college, living in Myrtle Beach at the time and attending Coastal Carolina College (before it became a part of USC). The coast had been evacuated and she was sent fleeing to Columbia. I was rarely able to see my sister, and when I did, it was a treat. She left early on the 21st and arrived by the afternoon, picking up my middle sister and I from school.

On that ride home from school the clouds were the darkest I'd ever seen from the outer bands as they got closer.

That night, we all huddled in our small, brick house. We moved from the bedrooms into the hallway, where there were no windows. My sister had turned our house into something of a zoo, with various pets (hamsters, turtles, rabbits, a cat and a dog). So they, too, had to be "safe" in the hallway with us.

I mention that our house was brick because you typically think of your house being a sturdy, immoveable place. But I still remember the feeling of our house swaying and creaking as the nearly 100 mph winds pushed through.

I mention that our house was brick because you typically think of your house being a sturdy, immoveable place. But I still remember the feeling of our house swaying and creaking as the nearly 100 mph winds pushed through.

The windows rattled loudly and constantly for hours. I don't know when I fell asleep, but it was to a constant sound of bangs, whistles and rattles from the winds outside.

When I finally woke up all was calm. My father had dropped by after his overnight shift at The State Newspaper to check on us. Green pine needles covered the entire ground like carpet. Trash cans and pieces of shingles were every where. And downed trees littered the neighborhood.

I don't remember how long the power was out. But I remember it was long enough that I realized hot South Carolina summers were no fun without air conditioning.

Meteorologist Tim Armstrong, National Weather Service Wilmington, NC

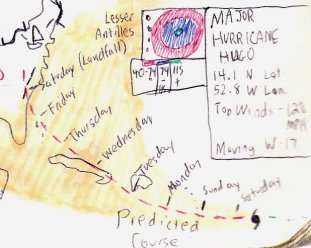

When Hurricane Hugo struck the Carolinas I was a middle school student in Catawba County, NC. Of the many interests I had (astronomy, meteorology, gardening, baseball, and more) meteorology already had risen to the top. I watched Hurricane Gilbert's progress across the Caribbean and Gulf of America closely in 1988. A violent tornado outbreak in western North Carolina on May 5, 1989 convinced me I needed to start tracking weather myself, so during the summer of 1989 I began keeping a daily weather log with maps, observations and my own forecasts. The PBS television program A.M. Weather, televised five mornings a week from 6:45 to 7:00 a.m., gave me an impromptu education in weather analysis, jet streams, weather map symbols, and a familiarity with the advisories, watches and warnings used by the National Weather Service.

On Friday, September 15, 1989, I scribbled down a forecast for Hugo showing a landfall along the South Carolina coast late the following week followed by a turn northward across central North Carolina. While this particular long range forecast turned out to be pretty good, in all honesty I tried to forecast every hurricane to take a path like that!

On Friday, September 15, 1989, I scribbled down a forecast for Hugo showing a landfall along the South Carolina coast late the following week followed by a turn northward across central North Carolina. While this particular long range forecast turned out to be pretty good, in all honesty I tried to forecast every hurricane to take a path like that!

As the unofficial "weatherman" for my school I was warning my classmates and teachers about what to expect from Hugo as early as Monday, September 18th. Hugo crossed Puerto Rico on Monday, and forecasts for an impact in the Carolinas became more emphatic as the week progressed. CBS's news program 48 Hours even devoted an entire show to Hugo which featured veteran reporter Bernard Goldberg visiting the National Hurricane Center and interviewing director Bob Sheets. I recorded this program and probably watched the National Hurricane Center segment a hundred times, dreaming of what it would be like to work there.

On Thursday, September 21st I remember telling everyone at school Hugo would be like an 8-hour long thunderstorm. In my weather log I went with a forecast of winds 25 to 35 mph with gusts to 60 mph, but it was still hard to fathom damaging winds could occur with a landfalling hurricane all the way up in the North Carolina foothills.

Around 4:30 a.m. on Friday September 22, 1989 I was awakened by the sound of strong wind gusts. Standing by my bedroom window for the next two hours I watched wind gusts exceed 40 mph, then 50 mph, then 60 mph. Large White Pine trees in my neighbor's yard twisted and bent 45 degrees in both directions while huge limbs cracked and fell a hundred feet down from tall Tulip Poplar trees. Despite not hearing thunder I was amazed by the frequent flashes of blue lightning occurring low in the sky in all directions. I didn't realize it at the time but I was watching power lines arcing as trees fell across them. As late as 7:00 a.m. we still had power although our cable TV service was already a casuality of the storm. I managed to watch a few minutes of local news via antenna informing me how bad conditions were overnight across South Carolina and into the city of Charlotte about 50 miles away. Then the TV and lights died as Hugo's wind gusts approached hurricane-force in my backyard -- over 200 miles from the ocean.

The needle on the barometer on my parents' living room wall pointed well below where I'd ever seen it and fell at an alarming rate: 29.40 inches, 29.20 inches, 29.00 inches, and finally bottomed out at 28.89 inches of Mercury (978.3 millibars) around 7:30 a.m. Although I had no way of knowing at the time, this was only a little higher than the 28.79 inch (975 millibar) minimum central pressure used by the National Hurricane Center in their 8 a.m. advisory as Hugo accelerated northward across Burke County, NC.

As the sun rose behind a thick overcast I finally ventured outside and couldn't believe the sound of the furious wind gusts. About once every minute a tremendous blast of wind 60 to 75 mph from the southeast tore through, accompanied by the cracking sounds of tree limbs and occasionally entire trees. In between these gusts, winds were no higher than 20 mph. The air had a swampy scent -- probably the result of the tremendous volume of various-sized tree debris which piled up like snow, covering roads, cars, yards, and even the sides of houses. The low ragged clouds were racing off toward the northwest at speeds I could hardly believe. Although I didn't personally witness rotation or any tornado-like lowering of the cloud base, I later saw signs of many short-lived tornado touchdowns where every tree was either uprooted or snapped off 10 to 20 feet above the ground. The largest of these areas of complete damage I saw covered an area approximately 500 feet long by 150 feet wide along Robinson Road between NC Highway 10 and Sandy Ford Road. As late as the year 2005 it was still possible to see numerous rotting tree stumps and toppled tree trunks in this area, along with a noticably reduced forest canopy height.

As the sun rose behind a thick overcast I finally ventured outside and couldn't believe the sound of the furious wind gusts. About once every minute a tremendous blast of wind 60 to 75 mph from the southeast tore through, accompanied by the cracking sounds of tree limbs and occasionally entire trees. In between these gusts, winds were no higher than 20 mph. The air had a swampy scent -- probably the result of the tremendous volume of various-sized tree debris which piled up like snow, covering roads, cars, yards, and even the sides of houses. The low ragged clouds were racing off toward the northwest at speeds I could hardly believe. Although I didn't personally witness rotation or any tornado-like lowering of the cloud base, I later saw signs of many short-lived tornado touchdowns where every tree was either uprooted or snapped off 10 to 20 feet above the ground. The largest of these areas of complete damage I saw covered an area approximately 500 feet long by 150 feet wide along Robinson Road between NC Highway 10 and Sandy Ford Road. As late as the year 2005 it was still possible to see numerous rotting tree stumps and toppled tree trunks in this area, along with a noticably reduced forest canopy height.

We were without power in my neighborhood for three days. Since water was provided by an electric pump, we had to drive a few miles to church to fetch water for cooking, bathing or drinking. Although three days without power may seem bad, there were portions of the county without power for two weeks! The Catawba County school system was closed for several days as roads were cleared and damage assessed. Schools operated on a two-hour delay for roughly another week to give students without power at home extra time (and sunlight) to get ready for school.

Hurricane Hugo was without a doubt the most intense storm I have personally witnessed. Later storms (The Superstorm of 1993, Hurricane Floyd, Hurricane Charley, Hurricane Isabel, and Hurricane Irene) haven't eclipsed the wind speeds I observed during Hugo or had the same impact on me personally. Let's all hope it's at least another generation (or more) before a storm of Hugo's caliber strikes the Carolinas again.

Stan McKenzie, owner of McKenzie Farms, Scranton, South Carolina

I think the eye passed somewhere near Sumter, SC which is only 30 miles away. That town was devastated by Hugo as was most of the area. I had vague recollections of Hurricane Hazel in '54. I was a boy then and remember watching pine trees blow over from the winds. Hugo came at night and once it started blowing pretty hard, we lost power. The winds finally got so bad that we were actually afraid the house was going to be destroyed. I live in a brick home but we could feel the whole house moving! My wife got a mattress and took all the children into the interior hallway in hopes that we would have a better chance of survival there. When daylight broke, it looked like an A-Bomb had been dropped on us. My yard was a rubbish heap with huge 75 year-old pine trees laying all around the house. Luckily, not one of them struck my house and we were spared any severe damage. We were without power for about 3 weeks during which time we hauled water from the neighbors who had power restored and actually cooked on tobacco barn gas cookers. A cabbage crop that I had planted just prior to the storm came out of it in good shape and I made one of the best cabbage crops ever. I would have thought the transplants would have been blown out of the ground, but they were spared! Lots of memories of Hugo and most of them are bad.

Official Government Reports and Summaries on Hurricane Hugo

Natural Disaster Survey Report: Hurricane Hugo, September 10-22, 1989. This is a formal report compiled after any significant natural disaster. It gives a detailed summary of the storm, its impacts and effects from the Caribbean to the Carolinas.

National Hurricane Center Report on Hurricane Hugo. Storm summary with statistics and a meteorological history of Hugo.

Hurricane Hugo: Learning from South Carolina. A Report commissioned by the NOAA/NOS Office of Ocean and Coastal Resources Management discussing the damage observed after Hugo and recommendations to better handle the next storm.

Publications on Hurricane Hugo's Impacts and Effects

National Weather Service Charleston, SC Hugo 25th Anniversary Page. Video interviews with meteorologists and emergency management personnel who remember Hugo very well.

National Weather Service Charleston, SC Hurricane Hugo. Good summary page on the storm, including the transcript of an interview with Charleston mayor Joe Riley.

Hurricane Hugo: Storm of the Century. A well-researched magazine-style book detailing Hurricane Hugo's impact across South and North Carolina. Published by William J. Macchio and printed by J. R. Rowell Printing Co. of Charleston, SC. Since this is a copyrighted work only a few pages have been reproduced here. The book is out of print but can occasionally be found for sale on eBay.

Hurricane Hugo: South Carolina Forest Land Research and Management Related to the Storm. United States Department of Agriculture, Southern Research State, General Technical Report SRS-5, September 1996.

Hurricane Hugo in the Charleston Area by John F. Townsend, NWS Charleston, SC. A NWS Eastern Region technical attachment (90-7A) with unique local data of Hugo's passage through Charleston.

The Landfall of Hurricane Hugo in the Carolinas: Surface Wind Distribution. Weather and Forecasting paper written by Mark D. Powell, Peter P. Dodge, and Michael L. Black of the NOAA/AOML Hurricane Research Division

Hurricane Hugo's Effects on South Carolina's Forest Resource. Hugo's powerful winds damaged over 4.5 million acres of forestland in South Carolina

Carolina Bird Club's report on tropical and oceanic birds that were transported well inland by Hurricane Hugo.

Mariners Weather Log, Spring 1990. A National Weather Service publication focusing on marine weather events. The Spring 1990 issue featured a review of the 1989 Hurricane Season including Hugo written by Max Mayfield and Bob Case from the National Hurricane Center.

Weather Words, October/November 1989. A publication of NC's Agricultural Extension Service with several pages on the storm's impacts across North Carolina.

Hurricane Hugo--An Eyewitness Account by George Metts. George Metts was a paramedic in McClellanville, SC working in the emergency evacuation shelter Lincoln High School as Hugo's storm surge swept into the building.

Hugo: Catalyst for Change. For the 10th anniversary of Hurricane Hugo the South Carolina Emergency Preparedness Division used Hugo's images and stories for their program for that year's South Carolina Hurricane Conference.

Hugo: How It Changed South Carolina. The State newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina.

Interesting Hurricane Hugo Videos and Photos

Video of Hurricane Hugo's impact in Myrtle Beach, SC taken from South Carolina Governor Carroll Campbell Jr.'s helicopter as he tours the devastated coastline.

Home video of Hugo's impact in Pawley's Island and Georgetown, SC. Includes video from downtown Georgetown and the area near the steel mill.

Home video of Hugo's impact in Florence, SC. WJMX radio's morning show is playing in the background.

Video during Hurricane Hugo from Wrightsville Beach, NC, from WSOC-TV (ABC) Channel 9 in Charlotte, NC.

Hurricane Digital Collection from Georgetown County, SC. Many, many historic photos of damaged structures from Hurricanes Hugo and Hazel in the beach communities of Georgetown County and nearby Horry County, SC.

1999 Weather Channel Atmospheres special presentation looking back at Hurricane Hugo.

Page Author: Tim Armstrong

Page Created: September 16, 2014

Last Updated: September 21, 2014