|

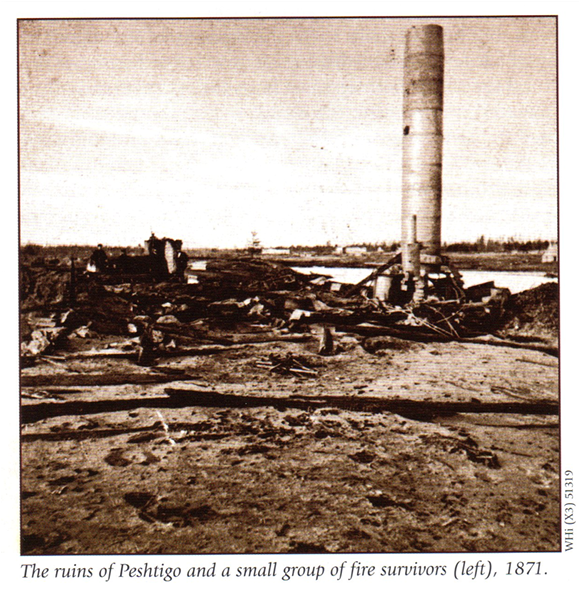

Figure 1: Peshtigo after the fire (Pernin 1999)

|

Fire reached Peshtigo during the evening of Sunday, October 8, 1871. By the time the fire ended, it had consumed ~1.5 million acres, and an estimated 1,200-2,400 lives (exact number unknown), including approximately 800 in Peshtigo. Only one building in the town survived the fire (Figure 1). What we know of the fire is primarily taken from the first-hand account of Reverend Peter Pernin. His account details a number of personal stories from those who were present in Peshtigo during the fire, and many of those personal stories are displayed alongside graves in the cemetery adjacent to the Peshtigo Fire Museum. One such story details the experience of the Kelly family (Figure 2):

"Terance Kelly, his wife, and four children lived in the upper Sugar Bush. When the fire came with the terrible wind and smoke, the family became separated. Voices could not be heard above the roar of the fire. Mr. Kelly had a child in his arms, as did Mrs. Kelly. The other two children clung to each other. In search for safety, each group lost track of the others. The next day, Mr. Kelly and a child were found dead nearly a mile from his farm. The mother and another child were safe. The other children, a boy and a girl, five, were found sleeping in each others arms near the farm. The house, barn, and all the outbuildings had burned to the ground."

|

Figure 2: Gravestone and story of the Kelly Family at the Peshtigo

Cemetery. Photo by Thomas Hultquist.

|

Click for larger image

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5 |

The fire in Peshtigo resulted from a number of factors, including prolonged drought, logging and clearing of land for agriculture, local industry, ignorance and indifference of the population, and ultimately a strong autumn storm system occurring in the presence of conditions supportive of a large, rapidly-spreading fire.

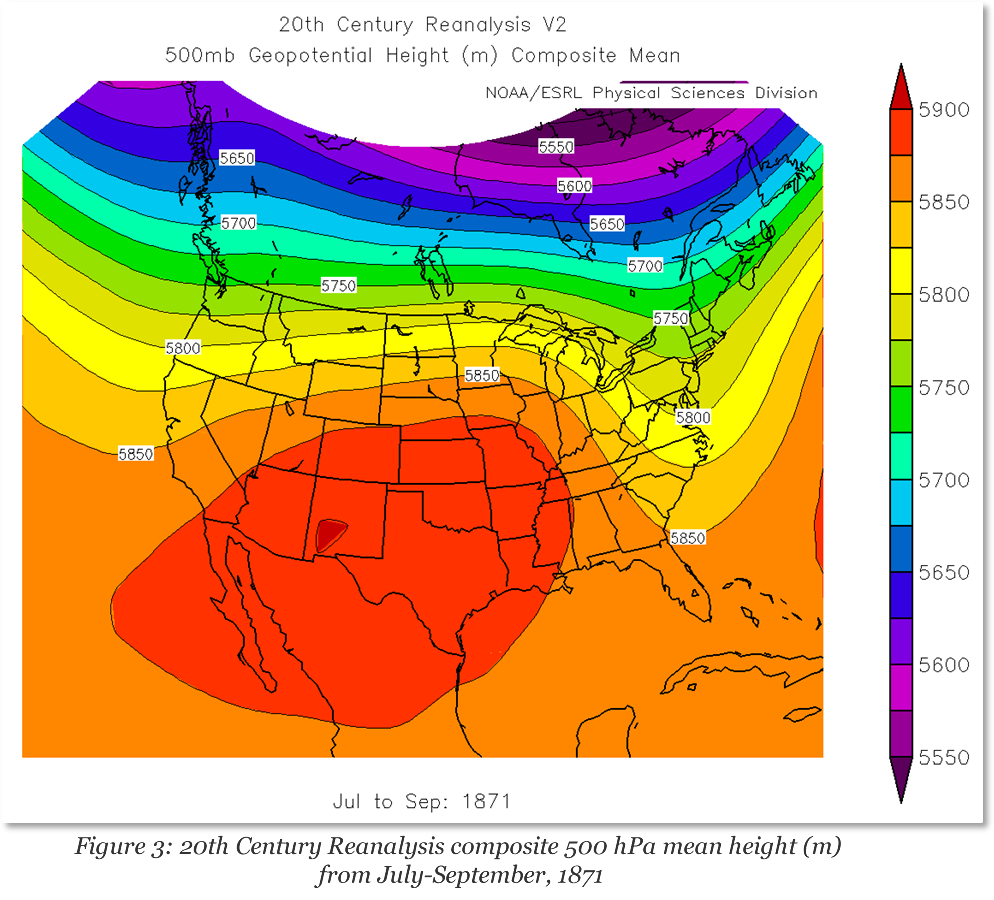

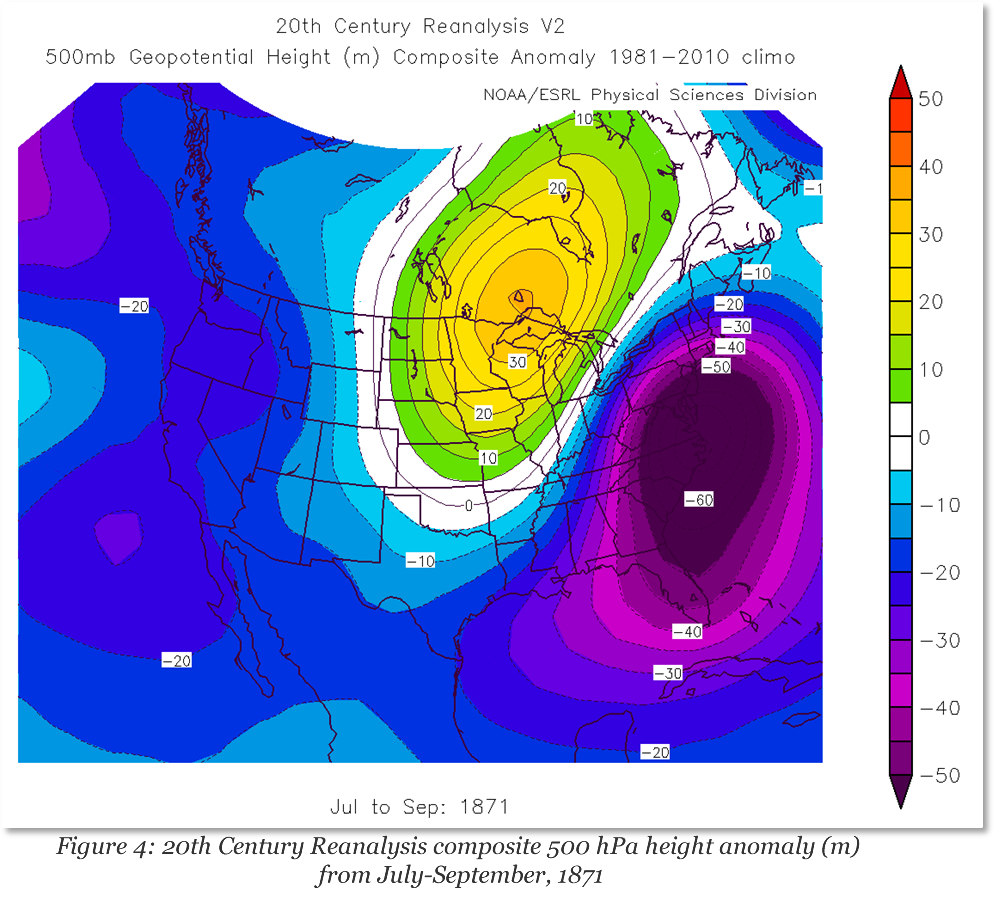

In order to better understand the large-scale weather conditions leading up to the fire, data from the 20th Century Reanalysis (which covers the period from 1871-present) was analyzed. A large upper-level ridge was present across the region from July through September (Figures 3 and 4), which would have set the stage for warm and potentially dry weather.

Reanalysis of 2 m temperatures from July through September indicates above-normal temperatures were present from the central Plains into the upper Midwest (Figure 5).

|

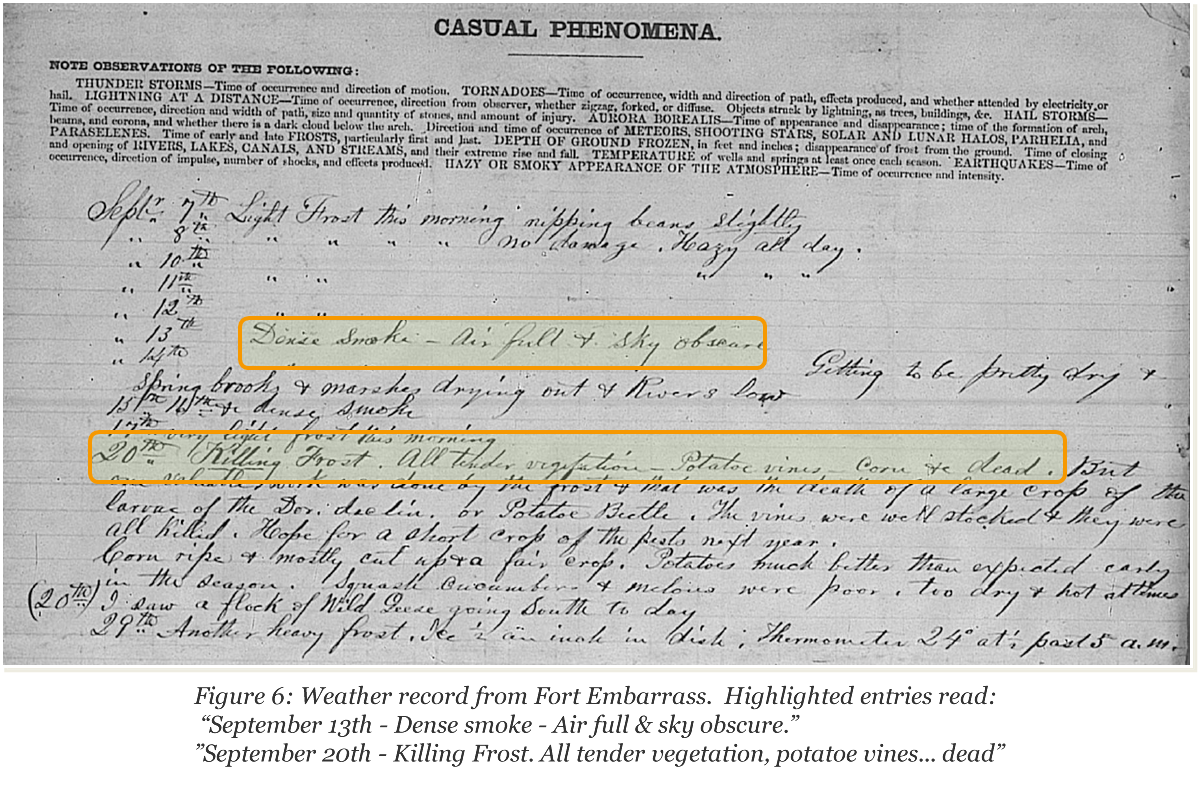

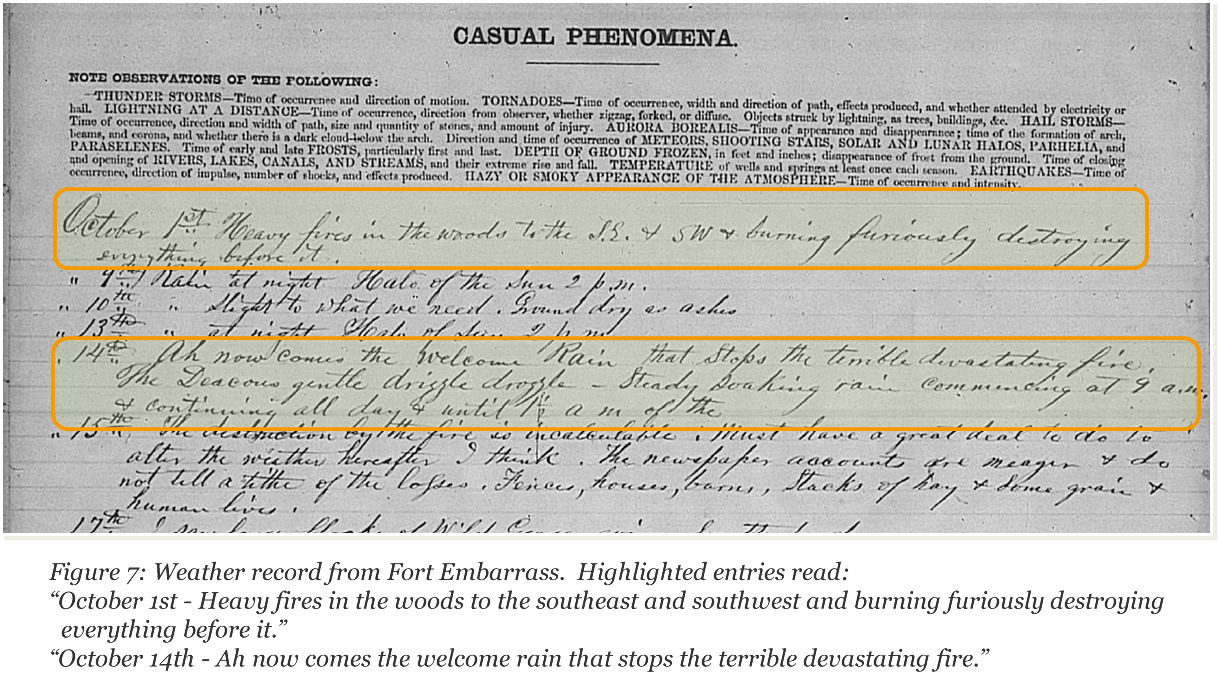

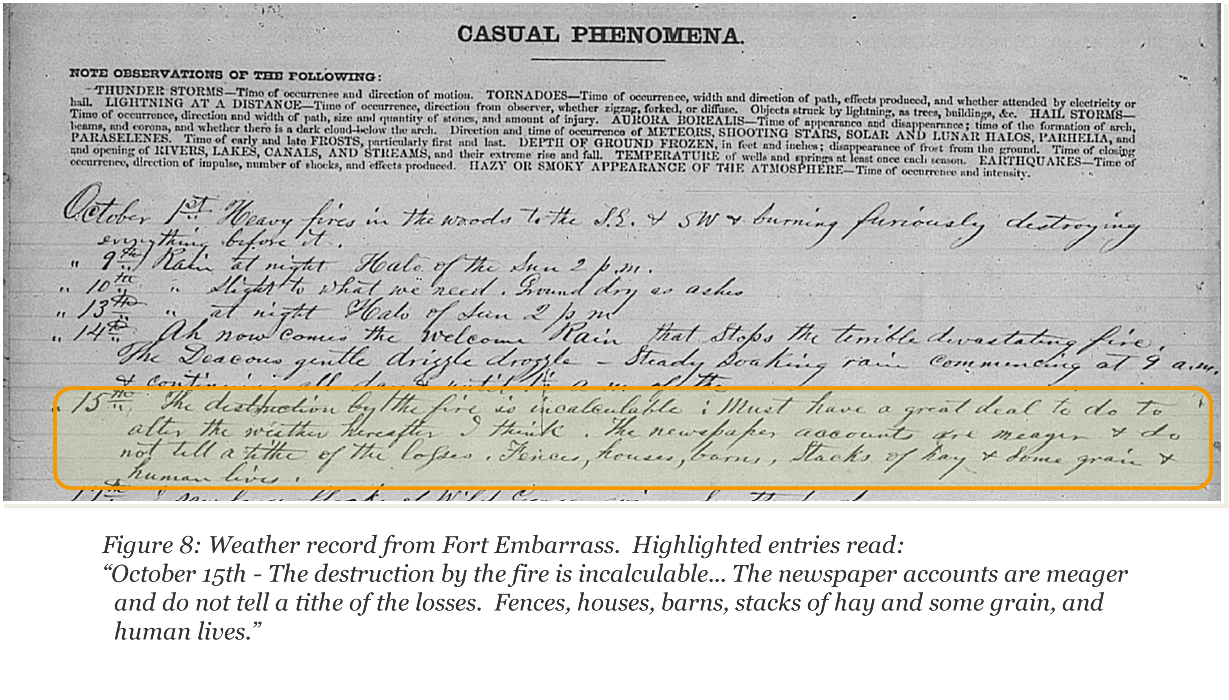

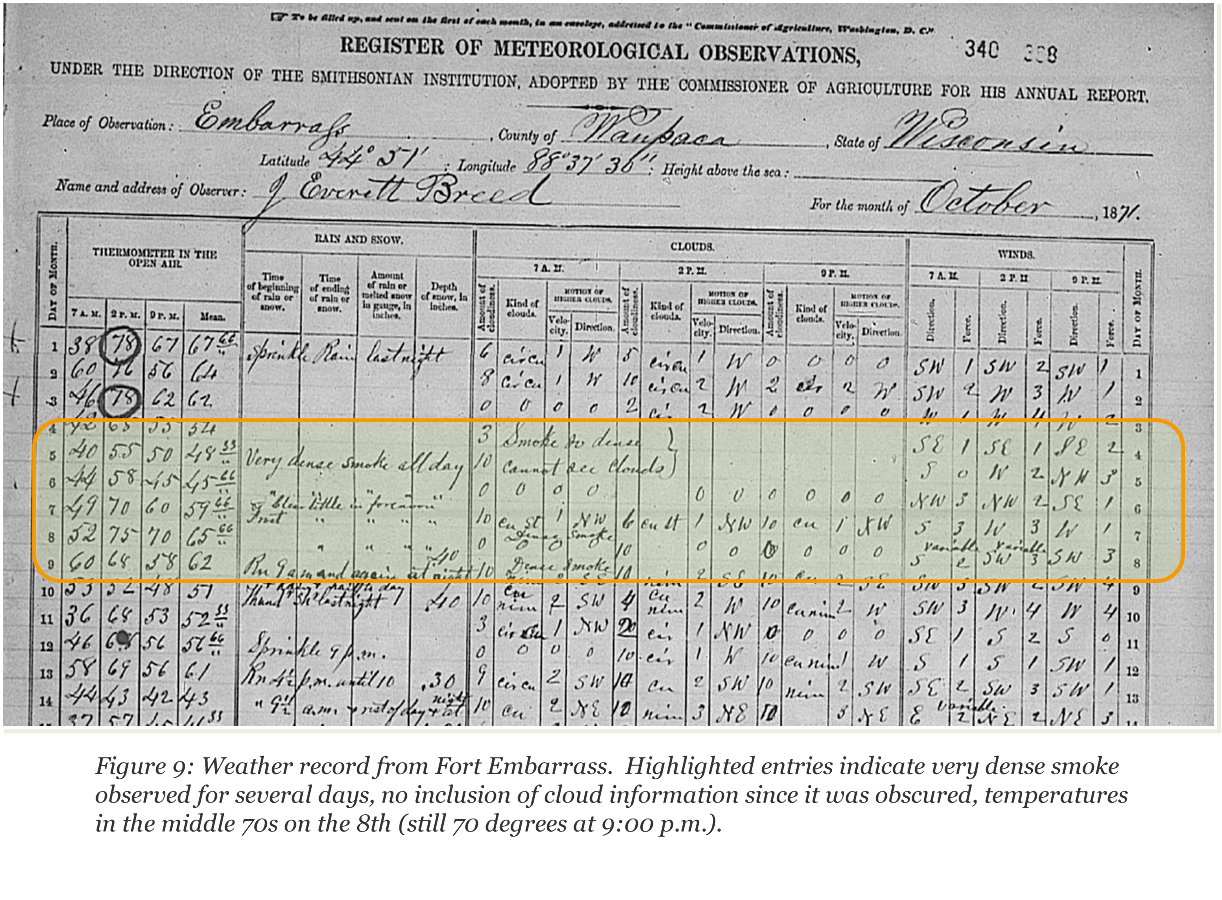

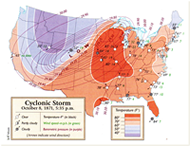

| At the time, Fort Embarrass, approximately 60 miles southwest of Peshtigo, kept detailed weather records. Comments from their observers in several entries indicate smaller fires prior to October 8, as well as a record of the deadly fire itself (Figures 6, 7, 8). Dense smoke was observed for several days leading up to the fire, and temperatures in the 70s were reported on October 8 (Figure 9). Although observations were scarce at the time, a surface weather map on the day of the deadly fire was reconstructed from the available data, indicating a strong low pressure system over the central plains (Figures 10, 11), which would have produced strong southwesterly winds across the region. These winds, in combination with the warm temperatures and dry conditions, likely led to the rapid spread of pre-existing fires and any new fires that ignited. |

|

Figures 6, 7, 8 (Click for larger image)

Figures 9, 10, 11 (Click for larger image)

|

The fires of October 8-10, 1871 helped serve as a wake-up call to many about the land use practices of the time. Timber from cleared land was discarded without regard to its potential to fuel wildfires. The subsequent 144 years has seen an evolution in how to mitigate wildfire potential with varying degrees of success, but awareness of the issue has dramatically increased. Weather support has become an integral part of fire operations, for both planned burns and wildfires. The National Weather Service has Incident Meteorologists trained in providing remote and onsite support to firefighters who battle wildfires across the United States, and have also supported operations internationally. Although wildfires will always occur and continue to claim lives and property, improvements in weather information, land management, and general awareness of the danger of wildfires helps ensure tragedies of the scale that occurred in early October 1871 will not be repeated.

Acknowledgements & References

- Town of Peshtigo

- Peshtigo Fire Museum

- Wisconsin Historical Society

- NOAA / Earth System Research Laboratory

- Gess, Denise and William Lutz. Firestorm at Peshtigo: A Town, Its People, and the Deadliest Fire in American History. Henry Holt & Company (August 2002). 320 pp. ISBN 0805067809.

- Pernin, the Rev. Peter, "The Great Peshtigo Fire: An Eyewitness Account." Madison, Wis.: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1971. Reprinted from the Wisconsin Magazine of History, 54:246-272 (Summer, 1971). [New 2nd Edition (1999)]

- Pyne, Stephen J. Fire in America: A Cultural History of Wildland and Rural Fire. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997. [Pyne integrates the history of fire with ecology, agriculture, logging, and resource management. He includes a vivid description of the Peshtigo fire and the other fires of 1871.]

For more information on this article, please contact Tom Hultquist via email thomas.hultquist@noaa.gov

|