Periods of moderate to heavy lake effect snow will continue through Friday downwind of Lake Erie and Ontario. Several additional inches of accumulating snow are expected. A Pacific storm will bring heavy rain and mountain snow across California, the Southwest and Intermountain West today. Isolated severe thunderstorms and scattered flash flooding is possible across parts of southern California. Read More >

|

|

|

|

||||

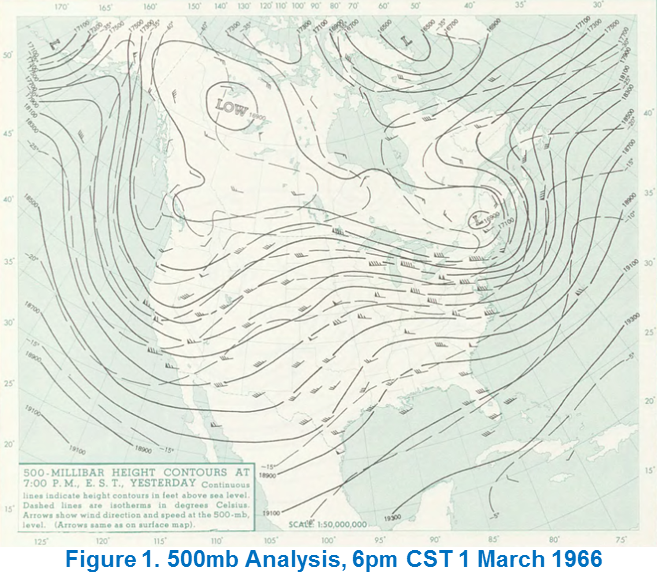

March 1st 1966 was a pleasant day across much of North Dakota. Temperatures were not extremely warm, but just slightly above average. Bismarck had reached a high of 34 and Minot climbed to 35. On the surface, it seemed like an ordinary late winter day across the Northern Plains. However, a change was taking place in the middle of the atmosphere. The 6PM CST weather balloon launches revealed a deepening trough on the west coast of the United States at 500 millibars (Fig. 1). A midlevel jet streak approaching 75 knots had begun to dig into southern California. By midnight CST on March 2nd, low pressure was starting to develop off the coast of Oregon after sliding down from the Gulf of Alaska. Another area of low pressure was starting to organize on the lee side of the Rocky Mountains in southeast Colorado.

By noon CST on March 2nd, the surface low over southeast Colorado had deepened to 988 millibars, with other surface cyclones located over southern Wyoming and central Nebraska both dropping to 992 millibars. As the west coast trough continued to deepen and the surface cyclones continued to intensify, winds began to increase drawing moist Gulf of America air northward towards the region. A large area of snow began to fall from southern Alberta, down to Utah, across southern North Dakota, and over to west-central Minnesota.

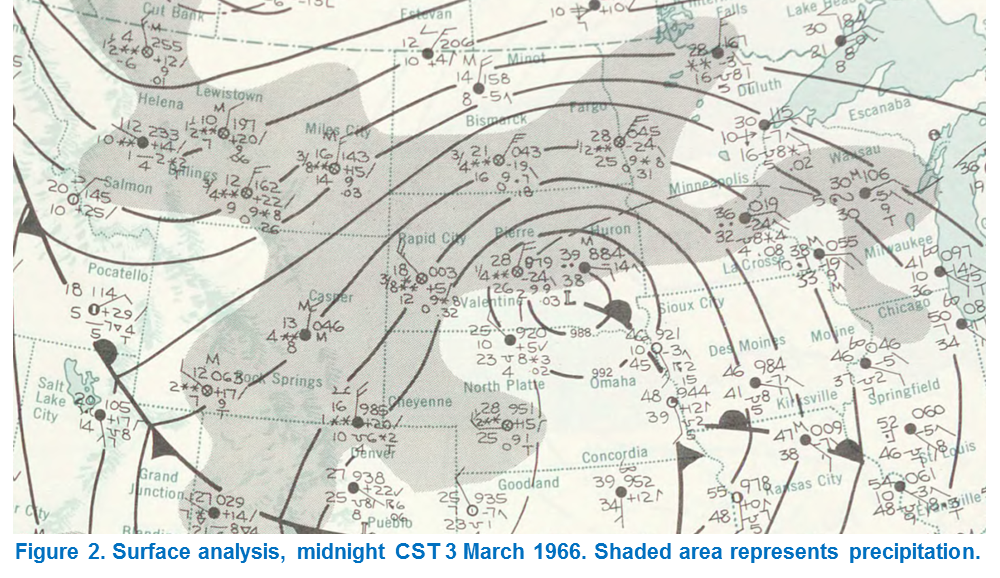

At midnight CST on March 3rd, the surface lows had merged over southeastern South Dakota. The center of the low was located just east of Pierre, SD which recorded an observed pressure of 987.9 millibars with moderate snow and a quarter mile visibility (Fig. 2).

At this time a very heavy band of snow was beginning to develop on the north side of the low, called a deformation band. As warm moist air pumps in from the south, it clashes with the cold arctic air making its way down from the north. The result causes a significant stretching in the atmosphere, and is where the term deformation comes from.

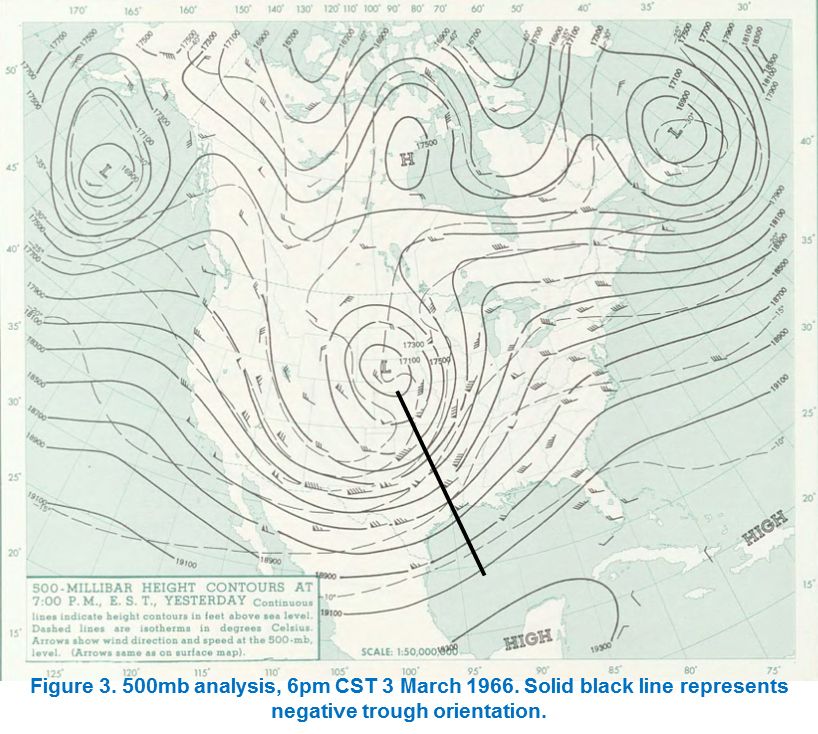

Surface analysis at noon CST on March 3rd showed the surface cyclone occluding over southeastern South Dakota. As a surface low occludes, the trailing cold front begins to catch up to the lifting warm front, and the low weakens. While the cyclone is weakening, it temporarily gets cut off from the upper level flow and remains stationary, along with the deformation band. The 500 millibar analysis at 6pm CST on March 3rd showed a significant negative tilt orientation (trough axis tilted towards the southeast) of the mid-level trough with a closed low centered over northern Nebraska (Fig. 3). The negative tilt was important because it suggests strong cold and warm air advection, necessary ingredients for a well-organized and intense deformation band of snow. Further, the negative tilt trough, in conjunction with a strong east coast ridge, helped to virtually stall the storm out over the region. These factors were important ingredients in the duration of heavy snowfall and blizzard conditions over the region.

The blizzard was still going strong by midnight CST on March 4th. A new surface low had formed over eastern Minnesota after the original cyclone occluded. For the first time in over 24 hours, the heavy band of snow began to finally drift further east. The new surface low deepened to around 986 millibars by noon CST on the 4th near the Minnesota Wisconsin border as the edge of the snow shield was approaching central North Dakota. By midnight CST on March 5th, the snow finally stopped in Bismarck as the cyclone continued to move out of the region.